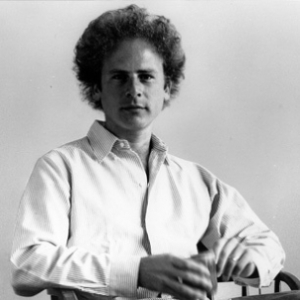

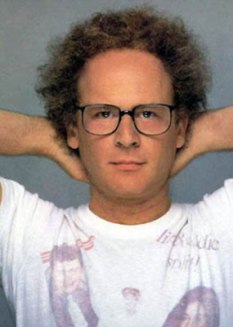

Art Garfunkel:

The BLUERAILROAD Interview

By PAUL ZOLLO

“Old Friends.” It starts so softly, two quiet chords taking turns, and then Simon alone singing “old friends sat on their park bench like bookends. . .” before he’s joined in harmony by his oldest of friends, Art Garfunkel, on the line, “Lost in their overcoats waiting for the sunset. . .” Later Garfunkel takes his turn, and sings alone “Can you imagine us years from today sharing a park bench quietly?” From Simon & Garfunkel’s landmark Bookends album, “Old Friends” is a song, like most of their work, which continues to reverberate long after the record is over, like an echo without end.

Art Garfunkel first experimented with echo when he was a kid, singing in the synagogue and the halls of his school. From an early age he recognized the almost holy quality of his own voice: an angelic, ethereal sound that excited his own ears before the rest of the world ever heard it.

“I learned how to sing with Artie, ” Paul Simon told us. “My voice was the one that went with that voice.” That Simon and Garfunkel grew up only blocks from each other in Queens, New York, and attended the same school is one of those enormously lucky twists of fate; lucky not only for the two of them, providing each with a counterpart in harmony both musical and personal, but for the world at large, who have been blessed by the magical sound of these two voices together .

Inspired by the Everly Brothers, Paul and Artie’s voices blended as if the belonged to brothers; listen today to “Scarborough Fair, ” “The Boxer,” “Homeward Bound” or any of their other classic duets, and experience a sensation that was especially soothing in the turmoil of the sixties, and resonates today every bit as powerfully, the sound of two voices singing from a shared soul. It’s a sound that their engineer and producer Roy Halee said couldn’t be achieved when they separately overdubbed their vocal parts onto tape. But when Simon & Garfunkel sang together at the same time, it was magic.

They met backstage in a school production of Alice In Wonderland, but even before that Simon was intrigued by this tall, curly headed kid who could impress the girls with the sweetest and smoothest of singing voices. They teamed up as teens and at that tender age rehearsed like professionals, developing a miraculous precision and harmonic blend. To hide the ethnicity of their names, they adopted the names of cartoon characters instead, Tom & Jerry, and entered the world of rock and roll at fifteen with a song they wrote together and recorded called “Hey Schoolgirl.” The song was a hit and the duo began to live out their dreams while still dreaming them, appearing on Dick Clark’s “American Bandstand” as high schoolers. When their next song failed to fly, the duo broke up for the first of many times, and Tom became Artie again, and returned to the idea of a career in teaching.

In a different world, Art Garfunkel might have gone on to become a professor of Mathematics, quietly and contentedly aiming his enthusiasm for numbers at a classroom blackboard instead of at the Hit Parade. But through a series of twists and turns, most of which are detailed in the ensuing interview, Garfunkel teamed up many more times with his childhood friend, and made some music that changed the world. Though he was never really comfortable performing in front of people, he recognized that in the recording studio he could bring his voice to a state of pure grace, a kind of perfection preserved forever in his spiritual singing on “Bridge Over Troubled Water” and so many others.

The partnership of Simon and Garfunkel, despite well- known accounts of their squabbles and differences, stands today as evidence of the power of real friendship; Garfunkel’s perfect harmonies added a depth and richness to Simon’s songs, while Simon continued to grow in his writing and provide Garfunkel with the greatest material a singer could ask for. When their time came to an end, and Artie was away in Mexico shooting Catch-22, the songs that Simon wrote reflected the sadness of their separation, two of the sweetest and most enduring songs of friendship ever written, “The Only Living Boy In New York” and “So Long, Frank Lloyd Wright. ”

As a solo artist, Garfunkel turned to the songs of some of the other great writers of our time, including Randy Newman and Jimmy Webb. Webb wrote “All I Know”, a soaring love song rooted in the gospel passion of the Baptist church ideal for Garfunkel’s angelic voice. It was the first hit from his debut album Angel Clare, which also featured an impassioned interpretation of Randy Newman’s “Old Man.” Garfunkel’s entire Watermark album was devoted to Jimmy Webb songs new and old, and it’s a treasure, featuring a heartbreaking rendering of Webb’s “Wooden Planes”.

Garfunkel is also a man of many other talents, as I was reminded more than once in our interview. Besides his acting in films from Carnal Knowledge through Nicolas Roeg’s Bad Timing, A Sensual Obsession, he’s also an excellent poet, having written a book of 84 inventive and poignant prose poems called Still Water, which was published by E.P. Dutton (now New American Library) in September of 1989.

He possesses a rare voice that seems only to be growing richer as he grows older. On his most recent album, Lefty, his version of “When A Man Loves A Woman” could bring warmth to even the coldest of hearts; it’s one of the most gracefully romantic records ever made, a hopeful and healing reminder that tenderness still exists in these turbulent times.

“I have to warn you,” he told me in advance of our interview, “Simon and Garfunkel was twenty years ago. I may not remember that much about my old group.” Given that, it was a happy surprise to discover that not only did Garfunkel remember the Simon and Garfunkel years, he remembered with them with vivid clarity, and with much humor and love.

Paul Zollo: You have one of the most amazing voices in music today. Was your voice a natural occurrence or did you work to develop it?

Art Garfunkel: Well, it’s a God-given talent and I observed that I had it at a very young age, maybe five or so. My parents both sang very casually around the house. My family bought a wire recorder in the forties when I grew up, and they would sing a little into the wire recorder. Not seriously but just to make music around the house, and I must have liked the pleasing sound and their harmony. There was a little singing in my childhood and I could do that myself, I realized. The next thing I knew is, with a little bit of practice walking to school – You know how when you’re walking on the pavement and you hit the cracks, you can get a song going to your walking step? – Well, I used to sing and when there was no one around, I could sing pretty loudly, and I thought I had a nice voice. So I would sing a song and then start again at the top and push the key a whole tone higher. I remember doing this as a young child. I must have been training. Taking this serious attitude.

What then happened was I fell in love with echo chambers. All the kids would be let out of school and you’d be at the back of the line. And you’d be humming something to yourself and the kids would go ahead, and you’d be in the stairwell with all those tiles and I’d start singing and it would sound really nice in the tiles. So everybody would go home and I would linger. And sing for about an hour or so. And I remember thinking, [laughs] “This is a really nice voice coming out of my throat. ” I was really digging the tiles but I did have a lucky thing going on there in my throat.

PZ: What would you sing to the tiles ?

AG: Songs I had heard on the radio. This was the Perry Coma era. Schmaltzy ballads. Plus there were certain inspirational songs that would get to me: “You’ll Never Walk Alone” from Carousel. Stuff with the goose-bumps used to get to me. And I would sing those.

And then I would sing a little in the synagogue. See, if you’re a singer, you love to turn your own ears on. You look for those rooms where the reverb is great. I remember the synagogue had a lot of wood and it was a great room. And it was a captive audience and you could sing these minor key songs and make them cry, and that was a thrill.

Then I would sing in grade-school when I was about eight. I bitched onto Nat King Cole’s hit, “Too Young.” [Sings] “They tried to tell us we’re too young. . . ” That was my song and I was totally identified with that. I sang it in the school talent show and got popular with the girls that way.

That got me a little into stage experience. They cast me in a play about Stephen Foster. I played Stephen Foster and sang “I Dream Of Jeannie With The Light Brown Hair” and some other Stephen Foster tunes.

I remember singing, [sings] “…a beautiful sight, we’re happy tonight…” [ “Winter Wonderland”] They cast me in some Christmas thing so I sang that. When I was in the sixth grade, Paul Simon, who grew up three blocks from me but I didn’t know him (he knew me, though), said, “I would see you in these talent shows in the 4th Grade. ” So by the sixth grade we met each other because we were both cast in the school graduation program, Alice In Wonderland. And he was the White Rabbit and I was the Cheshire Cat. There was no singing in that play but there was a lot of [laughs] humor and joking around and a really fast new friendship between the two of us backstage. So we became best buddies.

PZ: From what I understand, Simon was impressed by your ability to attract schoolgirls with your singing, and he wanted a part of that action.

AG: Yes, it was a means to popularity. That was the way you got to be known and he thought it was cool. And he’d seen me in the hall. “There’s that guy who sings.” And I would sing sometimes at the Jewish High Holiday services.

PZ: You would sing in Hebrew?

AG: Yes.

PZ: The Kol Nidre?

AG: Not exactly that one, but you’ve got the picture. It had all that embellishment stuff. Kvetches, as we call them.

PZ: Did you ever want to be a cantor?

AG : Yes. I did. Not as a real profession, but as something I might do around the Jewish New Year, the High Holy Days. Something I might do on a regular basis every year, I used to consider that.

PZ: Did you ever return to that?

AG : No. Not really. At Passover, I’ll get up over the wine and do a little thing.

PZ: When you began hanging out with Paul, did you hear him sing as well?

AG : Yes. When Paul and I were first friends, starting in the sixth grade and seventh grade, we would sing a little together and we would make up radio shows and become disc jockeys on our home wire recorder. And then came rock and roll. The very phrase was born through the mouth of Alan Freed as we were junior high schoolers. And when we listened to that subversive, dirty, rhythm and blues music on the radio, we know that was the cool stuff. It was the only thing in American society, aside from baseball, that had real genuine appeal and was not hype-y.

So we emulated the songs and practiced sounding like them and we tried to have our own record, and we knew we were going to try to get on a label, and we would work on our harmonies. And then we got remarkably serious in our rehearsals . We would have sessions that were so much about accuracy and patience and repetition and study. I would sit and examine exactly how Paul says his ‘T’s at the end of words Like ‘start.’ And where would the tongue hit the palette exactly. And we would be real masters of precision, figuring this would be the way to make it sound slick and tight and professional.

PZ: Were you driving force behind that precision?

AG : I would say yes. As a rehearsal freak, yes. Paul is a very creative artist but I’m more that thorough, meticulous, disciplined nut.

PZ: When you began singing with him, did you help him develop his voice?

AG : Well, “help him” sounds too much like spoon-feeding. I can’t really say it was that way. We were both copying what we heard on the radio. I wasn’t really teaching him anything. He was copying what I was doing a little. His tone got some of the mellow, airy sound that I had. I think he intuitively developed his style along my lines because I jumped in on it first. But it was all his doing and not my doing any teaching or anything.

PZ: Were the two of you able to harmonize together easily from the start?

AG : Yes, it came pretty naturally. I’m the kind of person who can hear that stuff. If you sing along to the radio and you’re not going to sing unison with the melody, but find the harmony, I find that pretty easy to do. Then came the magic words “Everly Brothers.” When they hit the radio with “Bye Bye Love,” we were really off and away. They killed us and we thought that was the coolest sound. We used to wait for their records to come out. So I think you can hear that they were a tremendous influence on us and on so many people. This nation should prize them as one of the great treasures of our musical history. Those guys were extraordinary. Not only because they were so damn good. but they were so cool; their sound was so neat, and so unlike anyone else.

PZ: In your early songs with Simon, you often sang melody and he would sing a lower harmony. How did you develop that idea?

AG: The song seems to ask for the harmony. You do two things: You try not to repeat yourself shake up the formula and observe what the song and the lyric and the arrangement seems to call for. We do that, for example, on “Sounds of Silence.” I sing the melody. We pitched the song fairly high because I’m a tenor. That left Paul below me, looking for a harmony part. I don’t know how we originally come up with these things…

PZ: Do you recall constructing that harmony part with him? Would you do it together?

AG: We were in my kitchen in my apartment on Amsterdam Avenue, uptown in Manhattan, when I was a student at Columbia College, actually, in the Architecture school. Paul would drive in from Queens, showing me these new songs. And that was the sixth song he had written, “Sound of Silence.” And he showed it to me in my kitchen and I went crazy for how cool it was. Then, I don’t remember us saying, “Who’ll do melody?” It could be he said, “I have you in mind for melody,” I don’t know… which necessitated it being fairly high. No, I can’t remember us working it out.

PZ: Since you mentioned studying architecture, I wanted to ask you about some of the Simon and Garfunkel myths to see if they are true. One myth is that when you went by the name of Tom and Jerry that your pseudonym was Tom Graph because you loved doing graphs, and you were really into math.

AG: That’s right. I used to chart the records. I used to listen to Martin Block’s “Make Believe Bathroom” on Saturday mornings and put down the Hit Parade. I was in love with the Hit Parade for its own sake. Yes, I loved music but I [laughs] loved the Hit Parade. I loved the rise and fall of the records with their numbers. Records that went from eleven to four. It killed me because of the numbers. And I had my graph chart of all these things. And I was very mathematical, and I guess I chose that name the way adolescents will do. G-r-a-p-h.

PZ: Math was a strength you had that Simon didn’t share?

AG: That’s true, yeah. I used to tutor it, and made my money to go to college on, from that kind of stuff.

PZ: Were you actually planning to be an architect?

AG: I was going to architecture school, yes, but I did three and a half years in the architecture school with no real love or feel for it. I think I was foolish enough to be involved with the concept of myself as an architect rather than with designing and buildings, and [laughs] you know, architecture itself. And after quite a while I realized I don’t like to pick up a pen and freely sketch and let my imagination run towards structures. And if I don’t have that natural desire, what am I doing here? How did I let this illusion go on so long?

PZ: Back in the days of Tom and Jerry, I understand that you and Simon would write he songs together.

AG: That’s right.

PZ: Did you write “Hey Schoolgirl” together?

AG: Yes. “Hey Schoolgirl” with its phrase “Woo-bop- a-loo-chi-ba” somewhat taken from “Be Bopa Lula,” Gene Vincent’s hit, was our attempt to remember an Everly Brothers song that we had both heard one summer. We were apart, Paul and I, in different places for the summer and at the end of the summer we had both remembered this great record by the Everlys and we were trying to reconstruct it. . . and we were getting it wrong!

We were, in fact, writing [laughs] our own song, “Hey Schoolgirl, ” in an attempt to remember this Everly Brothers song. When we heard the real Everlys song we realized, “Well, that ain’t it, so the thing we were groping towards… is ours!” So we finished writing it and made a demo of it, and signed a contract with a small record company on the strength of it, because the guy was in the waiting room of the demo place, and we actually recorded it. It sold 150,000 copies.

PZ: You actually had a hit at the age of sixteen?

AG: Yeah.

PZ: When that happened to you, did you feel that you had started what would be a long career?

AG: No, I don’t remember thinking that. No, I was too realistic. At that age I knew that you can’t count on anything, that just because you have a singing voice doesn’t mean you have an automatic career. No, your point goes beyond my thinking.

PZ: How did you learn to be so realistic at such a young age?

AG: You just look at things. Nobody has automatic follow- up hits. Here I was copying the charts all the time. I didn’t see a talented first hit always lead to a follow-up hit. I knew how mercurial the whole thing is. So even though I thought we were good — I thought our harmony and our blend was real good — I thought we were competitive and had a shot at making it, but once we did have that first hit, I knew we had a chance of a follow-up hit, but you don’t count on anything. You just wing it. We had a flop and then another one, and then we disbanded the group.

PZ: Did you write other songs besides “Hey Schoolgirl” back then?

AG: Yes, we had a whole bunch of them we wrote together. Some were mostly mine with a little Paul on words and music, some vice versa.

PZ: Is it true that you and Paul used to hang around the Brill Building and walk into offices to play your songs live for people?

AG: Dozens of them. The Brill Building and 1615 Broadway , two blocks north of the Brill Building. The newer building . We’d knock on the doors, we knew the different companies we liked because we were listening to Alan Freed and we knew the different labels and they were all located there. We’d go up and we’d often sing live for the people. Which was very nervous-making, you know? They’re busy, so if they don’t like you, they cut you off right away. At the end of your first verse they say, “No thanks, we don’t need that. Got anything else?” [Laughs] You’re crushed because wait until they hear the middle part! You haven’t even gotten to the good stuff!

So, sometimes you play a demo for them and they pick up the needle about nine seconds in and look for other tunes. Sure, your feelings get kicked around.

PZ: Did the two of you ever have thoughts of being a songwriting team, like Goffin & King or Mann & Weil?

AG: No, because thoughts like that, those are extrapolations beyond what I was doing.

I was just doing it. I wasn’t standing back from it thinking what it could lead to, what the name of it is, I didn’t have such images. Rodgers and Hammerstein didn’t mean anything to me. I just wanted to have a hit, I just wanted to be like those people on the radio. It was all of a case of the present tense with no projecting into the future, particularly.

PZ: Why is it that you and Simon stopped writing songs together?

AG: Well, our whole friendship went into suspension over some thing that happened in those early days. So for about five years we didn’t hang out, we weren’t each other’s friends.

PZ: This started when you were seventeen?

AG: Exactly. And when we next got back together again, we were really on different footing. You know, those are very critical years in your development. So we were more advanced, collegiate types then, and now the world knew of this thing called Bob Dylan And Joan Baez and all that folky stuff. So now I just jumped from the late fifties to the early sixties.

PZ: So you’re about 21 now?

AG: Yeah, and we became friends again. In those interim five years, Paul had made many a demo and so did I. I had two different label deals and a couple of records out of a folkie nature, but I was basically an architecture student at Columbia

PZ: You put out albums under the name Artie Garr?

AG: Singles. Artie Garr. G-a-r-r. One night we Paul and I hung out. He showed me these things he was writing because, I think it’s fair to say, he was so impressed with Dylan.

PZ: Did you share that enthusiasm?

AG: To the extreme. Dylan was the coolest thing in the country. If you were a young person at that age, maybe you don’t go for Dylan’s gravelly style voice, but who he was and how different and bold his lyrics were, and his look, that was the closest thing the record business had to James Dean. His album covers, if you look at the early Dylan, you see a real charismatic choir boy star of a kid. I remember when Freewheelin Bob Dylan came out, his second CBS album, I was in Berkeley. I was a carpenter. This was my year off from architecture school getting field experience And I was singing at Berkeley in clubs as well as doing carpentry during the day. And I saw in the record store around early September the new freewheelin’ album. And there’s Dylan in the village walking in the snow, and the camera’s got an upward angle on him and he’s with his girlfriend. And I knew I had to try and make another record. [Laughs] That was such a great place to be!

So I came back home [to New York], ran into Paul, he showed me these new songs he had written, about two or three songs. And they were really wonderful. And I let him know how keen I was to work out harmonies for them. In my mind I was thinking, “This has got to make it now. Between the commerciality of these folky songs that Paul’s writing, and the blend that we had worked on in the past, which will now serve us, we should have a shot at a career.”

PZ: – Do you recall which songs he played for you?

AG: Yes. “He Was My Brother,” that was his first one. A song called “on A Side of A Hill” which ended up becoming the “Canticle” part of “Scarborough Fair.” The third one was probably “Sparrow,” “Who will love a little sparrow?” The fourth one I know was “Bleecker street.” He was probably up to three songs at that point. So these three did it for me. And then we started harmonizing them and we were giddy with joy over how appealing it was to our own ears. Before the world gets to know something that’s neat, you get to know it. And you’re your own spectator of what’s coming out of you. And it’s really kind of . .. delirious and happy. It made you want to giggle while you were singing, it was so much fun doing these things.

PZ: Had your voices changed at all by then?

AG: No… Paul seemed to sound a little better and we’d never done these kind of sweet folky things. We were young rockabilly when we were younger. So the fact that there was kind of an emotional, goose-bump, bittersweet quality was really nice for our voices. So it was a bit of a new blend to soften up this way. I guess that’s why there was something new and exciting to our own ears about it.

But we were deeply confident on the inside. I kept thinking, ‘ his has to do it. This is very directly appealing.”

We’d go to the fraternity house. It was a good place to practice. But we really wanted the kids to overhear us. And whoever heard us would go nuts over it. [Laughs] There was really a something going on there.

Paul kept writing these songs. A new one would turn up every three, four weeks. “Bleecker Dtreet” was the fourth, “Wednesday Morning, 3 A M.” was the fifth, and “Sounds of Silence” was the Sixth.

PZ: You wrote the liner notes to the first Simon and Garfunkel album Wednesday Morning 3 A.M. and in them you wrote that when you first heard “The Sound of Silence” that it took you by surprise, that level of writing. Do you recall feeling that way?

AG: No, I don’t. I might have been putting on a little bit of gloss for those notes. I was just reading those “Wednesday Morning” notes and they were embarrassing. I was mixing my version of Variety magazine jargonese a little bit there.

I remember thinking “Sound of Silence” was the best of all the songs he had written. It was just a notch above in terms of commercial appeal. But if I could rephrase the way I wrote those notes, I would be happy.

PZ: You also said in those notes that you were not entirely clear about the meaning of the song. Was that true ?

AG: Not really. What Paul was doing was touching images that can be taken a lot of different ways. I understood. I knew where he was coming from, what his sensibility was.

PZ: You put out that album with the original acoustic version of “Sound of Silence” to have it later overdubbed with electric instruments, which made it a hit —

AG: A whole year later. In that year, Paul gave up on Simon & Garfunkel, and America. He became a Yankee in London, a street-singer, folk club singer, making twenty, twenty-five pounds a night, which was great money for a college kid.

PZ: Why did he have then, after you had released your first album?

AG: Well, the album, after about a year of doing nothing, looked… defunct.

It was put out in the Spring of ’64. He left about a year later. I joined him in the summer of ’65 and he had already carved out a little niche in that sort of folk circuit of England. So I joined him on some tunes and worked out my harmonies; he had written four more since I had seen him: “Kathy’s Song, ” “A Most Peculiar Man,” “Blessed” and one other, “I Am A Rock. ” By then he was up to about thirteen, fourteen of them.

PZ: What did you do during the period when he was in London?

AG: School. I was probably finishing architecture and finally giving up to it. Returning to Columbia College, getting a Bachelor’s Degree, which is a period of my life in which I first fell in love with learning, per se. So I was not really thinking of music as a career at all.

This is the difference between Paul and I. He really had broken away from a sort of “proper” profession and was truly bohemian. He’s a musician’s son. So he had left America with this “I don’t really know what the future is, but I think I might be holding it in my hands in this guitar.”

I, on the other hand, was thinking, “My future’s probably going to be in some professional something. If it’s not architect, maybe I’ll teach or something. So my music was, in my mind, more of an avocation.

PZ: But even with such an amazing voice, you didn’t foresee a career as a singer?

AG: No. [Softly] No… I have other talents, Paul.

I teach well. I used to really like teaching a lot. I enjoyed it a lot and I was good at it.

PZ: Did you enjoy it as much as performing?

AG: I hated performing. I love to sing but I don’t love to sing in front of people. I don’t have much of a feel for performing. When I think of performing, I think of being so nervous you want to throw up. That’s what performing means to me.

Singing in the recording studio when there’s no one else around, that’s a whole different thing.

PZ: But even with that nervousness, you sing pretty beautifully in concert.

AG: Quiver-y. In the beginning. It took quite a while, a lot of shows, before I began to calm down a little bit. To this day I’m still just learning how to get comfortable on stage. I did a tour in Europe last October. And I like working solo and it was a lot of fun joking around with the audience, saying things. I’m only just learning how to do certain things.

PZ: Simon was always able to stand behind his guitar and play. You were more out there in a way.

AG: That’s right. And Paul has more, I think, of a feel for the stage. Whereas I have it more for the notes themselves. I love record making and mixing, arranging, producing. That I love. I love to make beautiful things, but I don’t like to perform.

PZ: So Simon & Garfunkel were essentially broken up when “The Sound of Silence” became a hit?

AG: Yes. I didn’t have a career point of view towards music anymore because our one album with CBS was a flop. So then I came home at the end of the summer of ’65 to find that that year and a quarter-old album had one of its tunes released with overdubbed instruments called “The Sounds of Silence” and it came out in September, ’65. And as it slowly climbed the charts, my life changed.

PZ: How did you feel, from a musical point of view, when you first heard the overdubbed electric version?

AG: I remember thinking, “Of course it’s not a hit. Because I never have hits.”

At that point I was very used to how hard it is to really make it, and just because you sing doesn’t mean you get anywhere. So I was very well practiced in disenchantment. So when I heard it, I thought, “Well, of course it’s not a hit” because a hit is a one-in-a-million thing. And I was lucky enough to have such a one. It will probably never happen again.

It was in that electric 12-string style of the Byrds. “Mr Tambourine Man.” Okay, so they did that to us. It’s cute. They’ve drowned out the strength of the lyric and they’ve made it more of a fashion kind of production. And you never know. I was mildly amused and detached with the certainty that it was not a hit. I don’t have hits.

PZ: When that did become a hit, did that influence Simon’s writing? Did he begin tuning them out more frequently?

AG: I would say no. He continued to do just what he was doing. I can’t say there was any alteration. He didn’t change his style, he didn’t change his speed of writing. He came back [from England] reluctantly, because he was in love with Kathy and England and his life as a free young Yankee. And he hated to have to relate to a hit record in America. Even though it was the thing we had long wanted, it came at an unfortunate time. It was the winter of ’65. And he only knew that it was happening when it broke the Top Ten.

So Paul came home, we met in the basement, we said, “All right, this thing we’ve been looking for all these years has finally happened. It behooves us to be smart and see if we could have a follow-up hit.;’ We turned all our attention to what would be the single we would put out, to secure this toe-hold we had in the business. To show people it wasn’t a fluke and to show people we could make an interesting record in a whole other vein. So our goal was to have a hit that was nothing like “The Sounds of Silence.” Just to show chart muscle in a different way.

“Homeward Bound” became that second record. I remember cutting it and then thinking, “It’s so important that it be commercial. And it’s not quite good enough. Let’s cut it all over again.” And from scratch we redid it. Went to Nashville. We redid it and it came out good. It went to Number 5 in the country.

Paul had just written it. It was one of the latest that he had written in England. He said he wrote it waiting in the train station around Manchester, wanting to get back to London where Kathy was.

PZ: When he would write a new song, would he play it for you on guitar?

AG: Yes. But through much of the time, he was writing them as we were touring together or working together. So I knew them very well; it was that thing he kept noodling on.

PZ: Would you ever give him input on a song?

AG: Yes. My head was always listening to these songs as records in the making. So I was always thinking of the structure, the length, the arrangement, where they were headed as the record they’d be.

Records have images. There are wet records and dry records. And big records… “Bridge Over Troubled Water” is a big record. There are lighter records. You know, there are forest-green records, there’s orange records. These are the pictures I’m using. These are production thoughts.

So as he was writing the songs, I was thinking of the instrumentation we would use, how thick would the record be, or is it more like a ditty.

I’d put it into a category: this is like the Del Vikings. It’s hard to put into words how I was thinking, but I’d look at the song as one of the elements that makes a record. The musicianship, the arrangement, the singing, are the others.

PZ: Would you work on your harmony parts separate or together?

AG: Together. If he was writing the song, I would start seeing, in just the sense I was saying now, the kind of record it was going to be and what the arrangement demands, and what my vocal part should be in the record. This was all emerging as the song was emerging. And we would feed off each other. I would throw back at him what progress I’m making and that would give him a sense of what he’s writing.

PZ: “I Am A Rock” was your third hit?

AG: “I Am A Rock” was third. It peaked at number three in the nation. And then we got a manager, Mort Lewis. Mort helped us in the touring area. We branched out to become touring artists. We had a nice show.

Then we tried a fourth single that was really arty.

PZ: “The Dangling Conversation”?

AG: Yeah. We thought, “Can we take the audience where we want to go now and do a ballad?” Because ballads are tougher to have hits on. Something slow and really intellectual and literary. Let’s see if they’ll go for that, because then we can take them anywhere

It turned out that we couldn’t. That record was not a hit.

PZ: Did that surprise you?

AG: A little bit. It informed me that you can’t exactly call your shots.

PZ: Did it change Simon’s writing at all? Did he try to steer away from those kinds of songs?

AG: I would say probably yes, a little bit. At least, you know, you start thinking of songs in two categories: singles and album cuts. An album cut can be as artful as it wants to be. A single should be under five minutes or under four minutes. There are certain things you think of in singles that you wouldn’t necessarily hold yourself to for an album. You look for a more memorable, repeatable chorus in a single, a shorter length. So, certainly for singles, we knew it was best to stay away from the long, intellectual ballad.

After “Dangling Conversation” we began taking albums much more seriously and doing them much more slowly and artfully as we were influenced by the Beatles.

So in ’66 we slowed way down for our third album. See, the second album was Sounds of Silence quickly put out because it had a hit single. Made in three weeks. But on the next album, Parsley, Sage, Rosemary and Thyme, I think we must have spent nine months making that album, which was sort of unprecedented . But it was such a labor of love and fun, that we thought we were breaking new ground in terms of how creative an album can be. It was something we just learned from what the Beatles were doing.

So when that album came out in late ’66, that gave us a certain stature in the business, which helped, because we had obviously spent more time and energy and creative powers on that album. It had that interesting “Silent Night/7 O’Clock News.” And it had “Scarborough Fair,” which worked great for us.

That was a lot of fun to do.

PZ: That was the one song in which you and Simon shared writing credit; he said you wrote the “Canticle” section.

AG: Well, we both wrote it. The lyric, as I said before, came from Paul’s second tune, which never made any of our albums, called “On The Side Of A Hill.” [ singing softly ] “On the side of a hill in a land called somewhere, a little boy lies asleep in the earth…” It’s an anti-war song. “While down in the valley, a cruel war rages, and people forget what a child’s life is worth…” A bit of that lyric ended up behind “Scarborough Fair” but the melody [of the “Canticle” section] I wrote. And I wrote it just to be contrapuntal, to weave and swell around the lines of “Scarborough Fair” to increase the flow of the record. So I took the writer’s credit.

PZ: It’s a beautiful counter-melody.

AG: Thanks. I could write about seven of those things in an hour. Every hour I could write seven more. Supposedly that’s an achievement in BMI terms for me. It’s like breathing, I don’t get it.

PZ: Why didn’t you do more of that, then, in other songs?

AG: He wouldn’t let me. [Laughs] No, just a joke! I don’t know why I didn’t do more of that. There wasn’t a need to do more of that. It’s a specialty thing; it treats a song a little like wall-paper to be weaving in and out between the lines. It makes the song a little less than a proper song. It works in record terms.

I don’t remember holding back, it just never came up that that would be the right thing to do on another. Here, for once, we were not starting with a Paul Simon song, we were starting with a traditional folk song, “Scarborough air.” It’s the nature of this flowing song that it could take this counter- melody. I can’t think of any other Paul Simon songs that could… maybe “The Boxer” could do that. No, “The Boxer” is too busy.

PZ: With lyrics?

AG: Yeah.

PZ: On “Scarborough Fair” did you both sing both parts?

AG: Yes. We probably did two-part harmony on the melody and then doubled it. So that gives a kind of tubular, strong, commercial sound to the front. Then on the “Canticle” part, Paul takes some of those lines and I take the others that are higher. And we double that melody. So there’s one voice unharmonized in the background but that one voice is doubled.

PZ: How did you learn techniques such as doubling voices, and did Roy Halee have much of an influence in that area?

AG: My guess is yes, that Roy had something to do with that. We did it a lot and once we started doing it, we liked the sound. It’s all over our records, doubling your voice.

PZ: Did you start punching in vocals about at that time?

AG: I can’t remember, but as you know, that’s a big phrase we use a lot, punching in. The world’s not supposed to know about that. [Laughs] It should seem like it’s seamless. But sure, we were fixing lines right from the beginning. That’s standard recording technique.

As the years go by, you get a little more insecure, so you get more finicky about punching in not a line, but two words. And as years go by, you Ret Ret more local about the fixes you’re making.

PZ: In “A Simple Desultory Phillipic” Simon wove your name into the song: “I’ve been mothered, lathered, aunt and uncled, Roy Haleed and Art Garfunkled.”

AG: What about it?

PZ: I was wondering if you appreciated it.

AG: I thought it was nice. I did appreciate it. I thought it was cute. Even though the sentiment is slightly negative. He’s implying that he’s been done to by these people. It’s just a touch of a dig.

Paul is like John Lennon. They’re feisty. There’s a rebellious attitude. You know, that’s very acceptable. It’s standard rebellious attitude stuff. The public tends to like that stuff. It shows that they’re feisty, that they’re not busy patronizing the proper sounding, wholesome phrases of the culture.

PZ: Simon said that in terms of record making, you, he and Ray Halee had a three-way equal partnership. True?

AG: I don’t know. Yeah, I guess. We all respected each other’s talents and we all fused what we did. It became, really, a mix.

Roy was very important in that we loved him so much and we pitched ideas to win him over. It was so much fun to turn him on and make him think we were great. So really, he was our audience. We were always throwing ideas with the hope that Roy would fall out of his chair with how neat that was. He was always surprising us. We’d be out with the musicians in the studio trying to show the drummer what we think he should do. And a half-hour later, we would come back and Roy would say, “Let me show you what I worked out in terms of the sound when you were out there. I want to put a reverb on the attack of the drum, but then…. ” [Laughs] He’d show us what he worked out and you’d go, “What a wonderful contribution! He’s just cooking away creatively on the engineering side while we’re working on the arrangement.” These things put wind in your sails. A lot.

PZ: Was Roy a perfectionist?

AG: Definitely. Roy has brilliant standards. Really a fine artist. There’s a difference between a Rolls-Royce and a Toyota, you know. And Roy is really a craftsman, a consummate artist. He’s a bit of a misfit in the eighties. They don’t do that stuff anymore.

PZ: Do you feel that Roy is out of date?

AG: Well, he’s having hits with Paul, so he’s not really out of date. But that kind of care and concern is no longer costworthy.

Talk to a record company executive and they’ll go, “Yeah, well, if he wants to do it, let him turn himself on, but it doesn’t mean anything commercially anymore. ”

I’m not saying this right because I do think it means some thing. Records became much cruder in the last twenty years. Let’s put it that way.

PZ: Simon said that he felt Bookends was the quintessential Simon & Garfunkel album. Would you agree?

AG: I don’t know what you mean exactly by that phrase. I think of Parsley, Sage as the first real album in doing what we do. Bookends is the one that had a theme running through the whole side one. That makes it literary and particularly interesting in that it has a theme, a theme of youth to middle age to old age.

But Bridge Over Troubled Water is the one with the most successful variety. Different songs strike out in different directions with different kinds of production. So it’s a kind of a showing off piece in the variety sense. It makes that album, in my mind, kind of the richest, because it goes in so many different directions.

PZ: Bookends features “Voices Of Old People” which is not really a song but a sound painting. Was that your conception?

AG: Yeah. I wanted to set up the song “Old Friends. ” And I wanted the actual sound of the old people on tape so you can feel what we’re talking about before we sing something about old people. I actually wanted to get their coughs, their wheezes, their sighs.

It was really going to be a collage of gutturalisms, real earthy sounds in the back of the throat. Not so much what they were saying but their vocal production, to see if I could capture older people that way.

But we had wonderful quotes from all these interviews I had done. I went to old age homes…

PZ: Did the people then know who you were?

AG: Yes. When they were real elderly, they dimly knew and didn’t care. Actually, they didn’t know. The lady who ran the place knew who I was and they would accommodate my interest and give me a nice serious treatment. The actual old people I spoke to, they were pretty old, so they didn’t know who I was. So it was just a case of cooperating. And I would be the sophomoric interviewer asking them about life itself But they said wonderful stuff . .

PZ: Did they know you were recording it?

AG: Yes.

PZ: Did they have any understanding why you were doing it?

AG: Not really. No.

PZ: You said the purpose of the piece was to introduce the song “Old Friends. ” When you first heard that song did you have a sense that Simon was writing not only about old age out about the old friendship between you and he?

AG: Yes. I like that song a lot. I think he wrote a gem there. Sure, I did.

PZ: Also on that album is “Mrs. Robinson.” Is it true that you were the one who told Mike Nichols that Simon had a song with that title?

AG: He was writing a song called “Mrs. Roosevelt,” Paul was. And he was going nowhere and h was going to chuck it. . Paul and I were in the sound stage at Paramount or MGM in Hollywood working with Nichols on the soundtrack of the Graduate. And we had sung “Sounds of Silence”; we had to re-sing it to put it in the film. And we had the other thing: “Scarborough Fair” came right off the record into the film.

We still needed one up-tempo tune that Paul hadn’t written and Mike was struggling. And I said, “There is an up-tempo song that Paul is despairing of, but it is very commercial. It’s called ‘Mrs. Roosevelt’ but we could change ‘Mrs. Roosevelt’ to ‘Mrs. Robinson.”‘

And Mike loved that thought, as if he knew right away this was going to work: “Let’s hear this up-tempo song.” [Sings] “And here’s to you Mrs. Roosevelt….” And Mike knew that that was going to work. Changed it to “Robinson.” Said, “Let’s try to put it down and see if it works against the picture. ” So you sing it against the screen. And all that existed of the song was the chorus. That’s why the verses are “Doo doo doo doo…” There are no lyrics there. And it worked.

PZ: Was he writing about Eleanor Roosevelt?

AG: Yes. The key to me was that he was chucking the song anyway, so we were free to hack it up and do whatever you want with it.

PZ: Then he wrote the rest of the song after the movie was released?

AG: That’s right. So by the time our Bookends album came out with “Mrs. Robinson” in it, a whole bunch of months later, if not a year later, now, the rest of “Mrs. Robinson” was written.

PZ: Do you have any memory of hearing “The Boxer” for the first time?

AG: Yeah, I knew “The Boxer” was great. For one thing, it’s a style that is our strong suit. Paul and Artie could sing most effectively when they were doing a Travis picking, very fluid, running-along-syllable-song like that. Whenever we did those folky, running things, the syllabication is ideal for what we had learned. We were tapping into something that went way back for us, and something we could get a blend on. So I always knew, whenever it was that kind of thing, I had a particular feel that I could do really well, and match Paul and make the whole thing ripple and articulate it just right. So just because it was in that category, I had a feeling that I could make it sound good. And the lyric is real nice. And the amount of labor in the studio was just unbelievable. That one took so many days.

PZ: Your harmony part on that one is a classic. Many people have learned how to sing harmony by imitating your part on that song.

AG: I’m doing a bunch of different things: I’m using the classic third above Paul, an interval of a third, and then I do variations, depending on what the lyric asks. [Sings] “I am leaving, I’m leaving ” Yeah.

PZ: Were there any instances of you commenting on the lyric of a song or making questions about the writing prior to making the record?

AG: Yeah, but here’s so many times, who can remember? I wrote some of the lines. Never took a writer’s credit because in spirit it was really a small two percent factor. But there’s some of my wanting in there. In “Punky’s Dilemma, ” which was written for The Graduate I wrote a verse in there [ Sings ] Wish I was an English muffin , ’bout to make the most out of a toaster, I’d ease myself down, coming up brown ” Think I wrote all that stuff.

I wrote [sings] “I’m not talking about your pig-tails, talking ’bout your sex appeal ” “Baby Driver,” which is a song on the back of Bridge Over Troubled WaterI wrote that.

PZ: Didn’t you have any desire to have credit? George Harrison recently said that he felt he should have received credit for lines he wrote in Lennon and McCartney songs.

AG: I’m surprised that he’s complaining about it. It does work that way and you don’t ask for credit when it’s happening because in truth, in spirit, Paul’s the writer. Yeah, I wrote a little of that stuff, but that’s just technically true. In spirit, and in essence of the truth, it doesn’t matter. So I don’t know, maybe I’m being foolish for not being technical Yeah, I wrote a certain portion of the things

PZ: Simon said you wrote the flute solo on “The Boxer.”

AG: I wrote a lot of those kinds of things. If you’re talking not about the song but the arrangement; now I wrote more than two percent. I wrote a lot of the parts that musicians played, solo and stuff.

PZ: Do you recall what made those huge crashes in “The Boxer” ? I once heard but it was you and Paul dropping drumsticks on a hardwood floor.

AG: [ Sings ] “Lie la lie”, crash ! That’s Roy’s sound effect, which became very much an effect that was used a lot in the seventies and the eighties. It became real popular. We used to call it “the door closing sound”. Roy knows about that. It was some trick he did engineering-wise.

We dropped the drumsticks on “Cecilia,” which is, if you remember, very treble-y and ticky-tacky and tinker-toys. One of the things that gives that effect is Paul and I, each with about twelve drumsticks, dropping them rather quickly on a parquet wooden floor and then quickly picking them up, bunching them up in our hands and dropping them again. Like twice per second. [ Laughs ] Like, seriously, dropping and picking, dropping, picking! And we got that down in rhythm. So the bunching, dropping sound, is very woody, ticky-tacky sounding, and runs through “Cecelia”.

PZ: One thing that Simon told me that was hard to believe was that when he first played you “Bridge Over Troubled Water,” that you didn’t want to sing it, that you thought he should sing it.

AG: Uh huh, that’s right, I thought he should sing it. He sounded real good on it. It was too high for him, so he went into falsetto on the high parts, and he has a really nice flutey falsetto. So I commented on that when he first played it for me, that he had a really nice falsetto and he sounded good up there. If you want to know the truth, that was one of about six billion generous things I tried to say to Paul. I call that simply in the category of a relaxed generosity of creative cooperation. I’m amazed that we’re talking about this twenty years later to this day as if there’s a thing or a story, or. When you say that you’re shocked, I go, “What are we talking about? Are you shocked that somebody says something that is relaxed and generous to another? Where’s the story there?”

PZ: I think he felt that it was his best melody to date and that only you could do it justice.

AG: People do very good work when they write in the spirit of a gift. He did write it for me, and because there was a gift- giving attitude in the writing, I think he wrote a little better than he usually writes. And he writes pretty good, usually. “For Emily, Wherever I May Find Her” is a very romantic ballad and the fact that it was written for me, I don’t know, it brought something else out in his writing.

PZ: When you first heard “Bridge, ” did you consider it to be one of his greatest melodies?

AG: Yeah.

PZ: Was it your idea to hold off the production until the third verse, to make that final verse so huge?

AG: Yes. Now, I wrote a bunch of chords that make up “Bridge Over Troubled Water.” The fact that the verses end with a piano part that elaborates the ending and all those chords that give it a turn-around that set up to the next verse. I wrote that stuff with Larry Knechtel on piano. Larry was the player. And I just heard something in my head; this is a producer’s moment when you start hearing what the record wants to be, and now you strain toward the musicians: “Give me something, no, it should be a few extra chords, no, give me a different set-up chord, no, that’s the wrong chord; something with a more seventh feel. Denser. There, that’s the chord. Now it should go from that chord to like a ninth. Tilt it just a little.” And I remember doing that kind of writing with Larry and a whole bunch of the chords that ended the verses came out of our work.

The song used to only have two verses and that’s what Paul wrote. But we knew that these two verses were working beautifully and what we had was not a gem of a record but an almost big record. It wanted to have another verse and the other verse wanted to open up and pull out all the stops, as if the song that Paul wrote is really a set-up for the final verse, which is really something else again. So, I guess that was my contribution.

PZ: To this day I can recall so clearly where I was and how I felt when I first heard the song. There was a quality in your voice that was so emotional and so beyond anything else we had heard. Did it feel that way to you as well?

AG: Well, the listener gets to hear the whole record from beginning to end in one shot. The maker fusses over it so much that you have to have the concept of the whole record in your head. And as I was just saying before, the concept of the last verse would be a surprise augmentation of power. And a considerable augmentation. That concept moved me and so I knew that the vision was wonderful. And when I recorded it, the fun was to do that last verse first as a vocalist. So peaking out on that last verse was fantastic, knowing where you’d come from and that you’d set it up with two quiet verses. Yeah, I had a great, spiritual time. A pole-vault. You know? You’ve only done seventeen-foot-six but suddenly you’re pole- vaulting thirty-four-feet-nine! And when you’re way up there, it’s a great life experience.

The second verse was a lot of fun. I knew how to do that. See, once the third verse is done, now you’re going back to do the second verse and you know you haven’t released it yet, the world doesn’t know it yet. It’s all saved up. It’s a lot of fun. It helps you do your work to have something so neat up your sleeve.

PZ: Did you record that song in L.A. ?

AG: The last verse was done in L.A.; the first two verses were done in New York.

ST. Do you think that had any effect on it, recording it on two coasts?

AG: No.

PZ: You said that after the release of “The Dangling Conversation , ” you realized you couldn’t put out a ballad as a single. Were you surprised that “Bridge” became such a huge hit?

AG: I thought it was a very strong five-minute tune and record and cut on an album. Real strong. So I had no false modesty that it came out real good.

But I thought it was an album cut. It took Clive Davis to say, “I think it’s your first single for this album,” for us to say, “Really? A five-minute single?” Clive Davis, president of CBS at that point, said, “Yes. Go for it. I hear it. ” It is real soft. When you hear it on the radio in the context of other records, it’s an awfully soft, slow, first verse. It takes a while before it proves that it sounds like a single.

PZ: It sounded so unlike anything else at the time both the comforting sound of your voice and the healing message of the lyric. Then “Let It Be” was released soon thereafter which had a similar tone –

AG: We thought “Let It Be” was very similar. How did they hear what we were doing?

PZ: McCartney did say, years later, that he heard “Bridge” and wanted to write a song like that –

AG: I see! How interesting. I never knew that. One day Paul [Simon] came in the studio, and I had done the first verse. And I had, [sings] “When tears are in your eyes, I will dry them all. . .” He said, “Where’s the octave leap?” Meaning, “Where’s the ‘I’ll dry them all. . [sings up an octave as on the record]’ ” You know, you jump up an octave, because it wasn’t working and I just dispensed with it. “Paul said, [In a high-pitched, upset voice] What a minute! You can’t take the writer’s notes and just dispense with them. I wrote that note. I’m the writer and that’s what I wrote!” [In a calm, soft voice. ] “All right, Paul, I’ll go out there and put the note in. ” [Laughs] I thought that was funny.

PZ: Were there many disagreements over directions you should take?

AG: Oh, there were a lot of points of view. But, I don’t know, that’s what makes things good. To be unafraid of calling it as your ears hear it, is to have truth and authority and identity and commitment and ears. Now, of course, it’s going to differ with the other all over the place, and the rest is can you be mature and not a pain in the ass about working out different ideas? See, you get a lot of mileage when you yield. Everytime you say, “I don’t hear it that way but let it be your way,” you create an emotional catharsis. And that’s one of the most valuable tools you’re dealing with in the studio. To yield is to create, in many ways. I’ve never heard anybody say this theory but if you know what I’m saying, there’s a real truth in there.

So it’s mix and match. Hold your line when you really feel something you’re saying is wonderful and you really want to get this point across and prove it to your partner by just throwing it into the tape and letting it speak for itself. At times; And then at other times you go, it’s a little arbitrary. I hear this but he hears that. Let me see if I can create the rush of cooperation by letting it be his way. So I’d play that game a lot.

PZ: You yielded on that octave jump in “Bridge. ” In retrospect, do you think that it was a good idea?

AG: Yes, although it’s somewhat arbitrary. It was a good idea but I don’t think it would matter, particularly, if it wasn’t there.

PZ: On that same album, there are two songs that Simon wrote to you, as opposed to for you, “So Long, Frank Lloyd Wright” and “The Only Living Boy In New York. ”

AG: That’s right. That is correct.

PZ: He wrote those after you went to Mexico to work on Catch-22 . When you went there, did you have any feeling that it might break up the team?

AG: No, there wasn’t at all on my part. And at first there wasn’t on Paul’s part. I went off to Catch-22 thinking I’d be gone two months, possibly three at the most. Because I had a small cameo role in the movie, and that’s the maximum it should take. Usually those kind of things can be done in three weeks.

So I was gone, at first, for what I thought was just a little interruption. See, our way of working was for Paul to write while we recorded. So we’d be in the studio for the better part of two months working on the three or four songs that Paul had written, recording them, and when they were done, we’d knock off for a couple of months while Paul was working on the next group of three or four songs. Then we’d book time and be in the studio again for three or four months, recording those.

So my thought was, rather than wait for Paul to write the next bunch of songs, I went off and did this movie. When Paul’s songs were ready, he was ready to be in the studio before I was finished with Catch-22.

And here, Mike [Nichols] held me in Mexico for like four and a half, five months. And I should have really said to him, “You don’t need me this long. I’ve got work in New York. You know? Call Paul Simon. Call Roy. What am I doing down here?” I should have said that. But I was many miles away. And you don’t realize what you’re missing when you’re out there.

The fact that it turned out to be that many months was frustrating. And that’s probably what meant to Paul that it’s going to be tough to continue this way.

PZ: Was it ever your attention to pursue acting as much as music?

AG: No, not at all. No. I thought… Here’s what it was about When we were making Bridge Over Troubled Water, and I forget how much of it had been already recorded when I went to Mexico. Maybe two thirds of the album was done.

When I went to Mexico, the feeling was that we weren’t having a good time. We weren’t enjoying ourselves. We were tired of working together. We wanted a break from each other. We were not getting along particularly well and there were a lot of conflicts that were unpleasant conflicts. They all took the form of music and what kind of record are you making but whereas in the past, differences of musical ideas, it was pleasant enough to work them out and get the maximum result. Here, on Bridge Over Troubled Water, it was not particularly pleasant at all.

I remember thinking, “When this record’s over, I want to rest from Paul Simon.” And I would swear that he was feeling the same thing, like “I don’t want to know from Artie for a year or so.” We’ve toured together, we’ve done so many things together for a whole bunch of years, we’ve had a great run in front of the world, let us privately now renew ourselves and get a reappreciation of the other one by cooling it for a while.

So my feeling was, “Sure Paul agrees that when this album is over, we don’t want to work together for a while. I’m sure he agrees. If he doesn’t, he’s crazy. This is not fun.”

Oddly enough, the results were coming out fine on tape. Because when you put on the earphones and go to work, I guess your commitment to art is greater than your lack of commitment to each other. So you always get responsible and serious toward doing your best work from the heart with all the beauty you have within you when it’s tape time.

So I went off to Guaymas thinking, “This is the right thing to do, this is fine. For Art Garfunkel to be a little bit of a movie actor in addition to my role in Simon & Garfunkel is very nice for the identity of the group. ” After all, Paul plays the guitar on stage; Arthur just has his hands. Paul writes all the songs. So it beefs up my side of the group.

I thought it was excellent. It’s almost as if George Harrison suddenly did an acting role to balance out the McCartney- Lennon contribution. My sense of show-business told me it was the perfect balance. And I thought I was going to help give my side of the group a little more interest to the public, and I’d be bringing it back to the duo after we had our rest from each other, and we’d go on and make more albums.

I was in love with Simon & Garfunkel. I thought we were a neat act. I didn’t want to tip that over, I just wanted to take a rest from it. And here, with the help of Mike’s offer, I wanted to enrich my side of the group with this acting role.

Well, Paul couldn’t abide by these things. They were evidently threatening. So, in his mind, waiting for Artie is something he couldn’t do. Now, I was waiting for Paul to write the tunes all the time, before we’d go in the studio.

PZ: When you heard “The Only Living Boy In New York” or “Frank Lloyd Wright, ” how did they strike you?

AG: “Only Living Boy” has a very tender thing about it. There’s something really musical and from the heart about that song.

I don’t know what it is, but it’s indescribably sweet. The attitude of the lyric. “So Long, Frank Lloyd Wright” is another kind of song. The chords don’t have quite that emotionalism. It’s more about cleverness. I think I go to the chords first to give you the answer, because chords are feelings, and that’s where the answer lies.

PZ: I always thought the beginning of ‘Only Living Boy’ was so touching, the way he refers to you as Tom, the name from your first childhood team.

AG: It’s sweet. “I get the news I need from the weather report” That’s Paul saying, “How’s it going down there in Guaymas?” I have a letter he wrote in those days that was really affectionate. You can see they missed me. I blew it by letting Mike Nichols hold me down there for so many months. That was a mistake on his part.

PZ: Those are two of his most moving songs, and they were both written to you —

AG: There’s a lot of depth of feeling between Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel mutually. A lot of depth of feeling. Our lives are amazingly intertwined. You don’t know the beginning of it. It’s extraordinary the way these two lives wrap around each other.

PZ: Your first solo album was called Angel Clare. Was that recorded in Grace cathedral?

AG: One of the tunes was. The Bach chorale was done in that cathedral in San Francisco. We had done that before. Paul and I had gone to a church on “The Boxer” to get the high ceiling stone sound. The “lie la ” were done there.

PZ: I thought it was interesting in the 1981 Simon & Garfunkel tour the way you added new harmonies to some of Simon’s solo work. I especially loved your part for “American Tune. ”

AG: Me, too. Well, I had a great feeling for that song. I had shown Paul the Bach chorale that is the basis of that song. Then we split up. Then Paul wrote “American Tune. ” And I knew that was the kind of song that was very Simon & Garfunkel. Had we not split up, that would have been a “Bridge Over Troubled Water.” I had a lot of fun writing that part because it had so much feel. I felt like I was partially the midwife that gave birth to that song.

PZ: Do you have a favorite Simon & Garfunkel song?

AG: The most organic thing we ever did is not even a Paul Simon song. It’s “Scarborough Fair.” It’s a traditional song. That’s he flowingest, most organic thing I think we ever did. As far as the favorite record we made, I would probably agree with the world. “Bridge Over Troubled Water.” Because the vision and the scale of the record is so damn big, and I thought we mostly succeeded in filling out that vision. So the bigness impressed me.

To have delusions of grandeur is usually a neurotic problem , but to fulfill the illusion of grandeur and make it… grander [laughs], was a lot of fun.

We human beings are tuned such that we crave great melody and great lyrics. And if somebody writes a great song, it’s timeless that we as humans are going to feel something for that and there’s going to be a real appreciation.

So I keep looking for the great songs thinking that I can do it. And I will do it. I can top “Bridge Over Troubled Water.” You know, that’s a wonderful record that’s real grandiose in its production and it’s a first-rate song, but there are other first- rate songs and I can sing as good as that if not better now. So I’m going, for the rest of my life, to want to top that, knowing I can do it.