A Bridge Built On The Blues

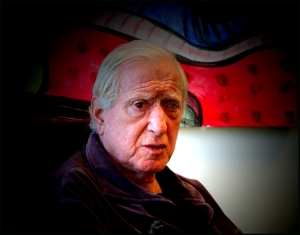

Written & Photographed by PAUL ZOLLO

Talking today to Leiber and Stoller is a phenomenal experience for so many reasons, not the least of which is that there are so many unlikely components to their story. Like any meeting with a legendary songwriter, there is the surreal realization that their songs are infinite and everywhere at once, yet the songwriters are quite finite and human even, sitting here in the same room, bound by time while their songs are timeless and unbound. Two Jewish boys from L.A. who got famous for writing in a black genre, they are now American icons who are integral facets in the history of rock and roll. Yet have rarely spoken to the press in the 56 years of their celebrated collaboration, and have never really participated in their history as it’s been written.

Their feelings about their now-mythic songs are bittersweet, and quite often more bitter than sweet. And almost every one of the published stories which purport to get their history right are wrong, including those surrounding the writing and recording of their most famous songs, such as “Hound Dog” and “Jailhouse Rock,” both recorded by Elvis, or “Kansas City,” recorded by the Beatles among many others, or “Stand By Me,” recorded by Ben. E. King originally and later John Lennon. [The Beatles also two other songs by Leiber & Stoller’s songs on their first demo, “Searchin’” and “Three Cool Cats.”]Their career stands as a turning of a page, a transition from the age of Tin Pan Alley, the epoch in which not one but two people toiled to churn out songs – into the age of Rock and Roll. Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, who share a suite of offices in the 9000 building of Sunset Boulevard, a building where some august veterans of the Tin Pan Alley age once had their offices, such as the wordsmith Sammy Cahn, have met here on this autumn day in Hollywood to give a very rare interview about the career that created many of America’s most famous songs.

Leiber, the lyricist, and Stoller, the melodist, came together just as Ira and George Gershwin did a couple of decades before them, to write songs for America and the world to revel in. But unlike the Gershwins, the most famous songs that Mike and Jerry created were part of a new era – though they came together just like those legendary writers of old – they were the architects of a new sound, a new craze, a new era of wild rhythm and bluesy tunes. It was rock and roll. It was a bridge from the blues – in which both Leiber and Stoller were well-versed – to popular music, a bridge they built themselves.

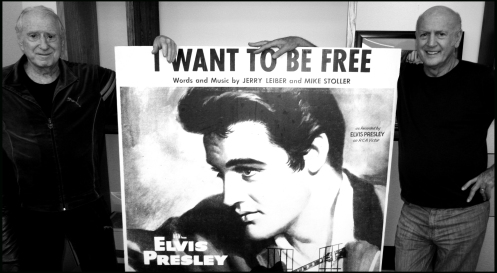

This suite of offices is appointed with large, brightly colored folk-art paintings of the blues heroes who painted their youth with their blues tales of life in urban centers like Chicago, far from their sunny Angeleno homes. Muddy Waters, Robert Johnson, Willie Dixon. These fathers of the blues hang over their heads in multichromatic glory, sharing the wall-space with only one messenger of rock and roll – a young man who, in black and white, remains as electrically vital as these blues beacons – Elvis Presley. Their lives and that of Elvis’ are forever entwined, and though his image is monochromatic here, his presence in their life is full of technicolor radiance and unfaded glory. And their memories of the King – which is frank, forthright, and unqualified – related here for the first time in unexpurgated detail, remains as alive as Elvis himself is said to be.

Elvis Performing “Hound Dog” Live on the Milton Berle Show

It is true, though, that, as reported, Stoller didn’t like the idea of writing songs with Leiber when they met in 1950. It’s not true, though, as has often been quoted, that he said he didn’t like songs. What he said he didn’t like were popular songs. He preferred jazz. But when he realized that the young Jerome Leiber had written not pop songs but blues, a bridge was built between them that still stands to this day. It’s a bridge built on the blues.Because their most famous songs came fast and easy to them, “hot off the griddle,” as Leiber put it, they don’t tend to value them to the extent that they value their songs like “Is That All These Is?”, an existential theatrical ballad made famous by Peggy Lee. To this day, Jerry and Mike yearn to be known as more than writers of simple rock and roll. When I lingered on the writing of “Jailhouse Rock,” for example, Leiber looked me squarely in the eyes and said, “Why are you spending so much time on ‘Jailhouse Rock’? Is it that important?”

Though they’ve written some of the most lasting popular songs ever, they didn’t think any of them would last. As soon as they were off the charts, they felt, they would vanish.Leiber & Stoller have long felt their famous rock and roll songs were kid’s stuff, and they wanted to write songs for adults – deeper, more musically and lyrically complex songs, of which there exists an abundance in their mythical “vault.” But except for “Is That All These Is?”, it’s their simple, easy songs that have connected them timelessly to popular culture. While countless songwriters attempted to approach the same kind of lofty heights Jerry and Mike reached, they were attempting to write songs like Brecht & Weill wrote, and to translate into words & music the synthesis of sorrow and humor found in the writing of Thomas Mann and other writers. Out of the universe of albums that have been recorded containing their songs, the one that they speak of with the greatest pride is Peggy Lee Sings Leiber & Stoller, a collection of their “adult songs” sung by the legendary vocalist.

And while you might assume any songwriter would be forever proud to have had a song recorded by Elvis or the Beatles, they never liked The King’s rendition of “Hound Dog” (and have never referred to him as The King, or even Elvis; in the following interview, he is “Presley.”) Nor did they like the Beatles’ record of “Kansas City” (for reasons also explained in the following.) They only wrote “Jailhouse Rock” because the movie’s producer refused to let them out of their hotel room till they came up with some songs. “Hound Dog” was written on the fly, and not for Elvis but for Big Mama Thornton. From the first second Jerry uttered its title, he didn’t think it was sufficiently explicit, and still doesn’t feel it’s as biting as he wanted. (Nor does he see much value in other legendary titles he’s created, such as “Jailhouse Rock,” or “Spanish Harlem.”) Elvis’s rendition of “Hound Dog” – perhaps the most famous record ever of one of their songs – doesn’t even use the right lyrics. Instead it copies improbable lyrics written for the song by Freddie Bell – who introduced the whole notion of a rabbit to the song – a notion that Leiber & Stoller regard as nonsense.

They were the first independent record producers to be officially designated as producers – ‘producer’ being a title they invented themselves (they wanted ‘director’) – but they started producing records only in self-defense, as they explain it, to ensure that their songs wouldn’t be wrecked.

Even with their most famous non-rock creation, “Is That All These Is?” they are forever dismayed by Peggy Lee’s insistence on changing one word, an alteration, in their opinion, that dilutes the entire point of the song. To this day, they often finish each other’s sentences, though their memories frequently clash. “Our relationship is the longest running single argument in the entertainment business,” Jerry said, only half-joking. But the connection that led them to write words and music like one person over the decades, even when they wrote them apart (they wrote the words and music to the refrain of “Is That All These Is?” apart, and then both parts fit perfectly and miraculously) is still powerful, and as often as they argue, they laugh, and it’s clear that there are few people they’d rather spend time with than each other.

We met on a sunbright day in Hollywood that had a shaft of darkness piercing through it – it was an anniversary of 9-11. But that tragedy didn’t darken our time together, which was originally only slotted to be less than an hour, and which extended, thankfully, to several hours. In their suite of offices up above Sunset Boulevard in the same building where Sammy Cahn and other legendary songwriters had and still have offices, we sat in Jerry’s office under bright folk art paintings of blues heroes, such as Muddy Waters, whose picture is behind Leiber’s big desk. Mike, who so seemed the embodiment of pure energy that I was prepared for him to leap up and run several miles at full speed, sat in front of a giant blow-up of the sheet music for their song “I Want To Be Free,” which was recorded by Elvis. The King’s iconic profile shone like the sun in stark black and white over Stoller’s shoulder throughout our talk, a presence that was both ghostly and vital, as is the enduring presence of Elvis in their lives. Stoller sipped Snapple out of the bottle as Leiber drank coffee from a white china cup and saucer, and the distinct dynamics that have been at play within this duo for more than a half century were very much alive, as the memories ripened and shape-shifted and the sparks flew between the remarkable man who wrote the music and the remarkable man who wrote the words.

BLUERAILROAD: Now the legend goes that Jerry wanted to get together with you, Mike, when you were both 17, to write songs. And you didn’t like the idea of writing songs.

MIKE STOLLER: Well, that’s not really true, but, you know, when you’re interviewed, frequently you give a very quick answer. The thing is, I assumed that Jerome Leiber was not writing something that I would be interested in. I had very specific tastes. I was a musical snob. I was a big Be-Bop fan. So I thought he would, somehow, be writing songs that I just wouldn’t care for. That I’d consider commercial, which was a terrible word among jazz musicians. I wasn’t a jazz musician. I played a little bit. But I had that kind of an arrogance, if you will. And when he came over, of course, I discovered that he was writing blues, and I loved blues. Cause it’s great stuff. I was a big boogie-woogie and blues fan, as was Jerry.

Before meeting Jerry, were you hoping to make your living as a musician?

STOLLER: I was hoping to make it as a composer, yeah.

Of jazz? What kind of music?

STOLLER: Just music. Of jazz, or of, quote, serious music.

Were you considering being a songwriter?

STOLLER: No.

And so you, Jerry, were writing blues without music?

JERRY LEIBER: Yes.

Had you worked with other songwriters before working with Mike?

LEIBER: Well, I worked with one other person who I wouldn’t really characterize as a songwriter. This was in high school. Going to Fairfax High School. I hooked up with a drummer. Whose name was… Jerry Horowitz. Is that his name?

STOLLER: I can’t remember, and he can’t remember. [Laughs] I remember what he looked like. Nice fella.

LEIBER: We worked for maybe two months, three months. One day he didn’t show up for a writing session. And it sort of went out the window. I needed a composer. Tunesmith. He told me he had a musician’s name written down who was a piano player that he played a dance with in East L.A. and he thought was pretty good. And he might be interested in writing songs. And he took his number down and gave it to me.I called – it was Mike – I called him up and I said, “My name is Jerome Leiber, and I was given your number by a drummer. Said he played a dance with you in East L.A. And he said you might be interested in writing songs. Can you write notes on paper?”

He said, “Yes.”

I said, “Can you read music?”

He said, “Yes.”

I said, “Do you think you’d like to write songs?”

He said, “No.” I thought what a tough nut to crack here. And I talked to him for a few more minutes. And sort of wrangled an appointment with him.

I took my school notebook, which had all my lyrics in it, and I went to his house. Which was at –

STOLLER: 226 South Columbia Avenue. Right where Belmont High School is.

LEIBER: I can’t remember the address. It’s been, what, 40 years?

STOLLER: 56. He’s a great lyric writer, bad mathematician. [Laughter]

LEIBER: I don’t have a very good memory, either.

STOLLER: That’s true.

LEIBER: So he was adamant. He didn’t want to write songs. He made it clear that he was doing me a favor by talking to me. He really wasn’t interested. He told me he was interested in Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Art Blakey.

STOLLER: Bela Bartok. [Laughter]

He was good, too.

LEIBER: Miles Davis. And I thought he was a terrible music snob. And I think so did he. But he did take the book out of my hands, and wandered toward the piano.

And he set the book down on the piano, and he started playing licks. Sort of blues-jazz. And he looked at the book and he said, “Hey – these aren’t songs. They’re not the kind of songs I dislike. These are blues, aren’t they?”

I said, “I think so.”

He said, “I like the blues. I’ll write with you.”

And that’s how it started.

The legend was that you said, “These aren’t songs, these are blues.” But did you consider them songs?

STOLLER: Well, they weren’t the kind of songs that I thought that he would be writing. Most of the blues that I knew – almost all the blues – first of all, were written by black people. And most of them by black singers and as a matter of fact, many, many of them were piano players, and I bought their records for the boogie-woogie instrumentals, which might have been considered, in those days, the B-side. You know, in the old 78 records? But I always played both sides. And the other side, frequently, which might have been the A-side, had the same person playing a blues and singing. So I did become somewhat familiar with the poetry of the blues and certainly the structure of the blues, and Jerry’s work was in that mode. It had the blues poetry in it.

LEIBER: Almost all of our audiences thought we were black. And when we took some of our music to a performer, to show it to him for approval or to teach him how to sing it, they were absolutely amazed. I remember we went to a little hotel down on Central Avenue. We were taking some songs to Wynnonie Harris, who at that time was pretty hot. And we knocked on his door, and he opened his door and he looked at us in shock. At first he really didn’t believe that we were songwriters. That’s how it went for years, actually. It wasn’t just the first five minutes. That’s how it was for years. And some people, today, still think of us as black songwriters. In fact, LeRoi Jones wrote an article about us. He said we were two of the best black songwriters in the business. And he meant it.

STOLLER: But when “Smokey Joe’s Café” went into rehearsal for the Broadway production, three of the guys met us for the first time, and were shocked. And this was ten, twelve years ago. They thought that we were black.

Those first lyrics you wrote, did you intend them to be blues?

LEIBER: Well, they were blues. The form, the structure. There were repeat lines –

STOLLER: Yeah. I looked at it, I said, “There’s a line, a line of ditto marks, a rhyming line.” I said, “These are 12-bar blues.” I didn’t know that you were writing blues.

LEIBER: He turned to me and said, “These are blues. These are the blues… I like the blues.”

I understand one of the first song you wrote together was “Kansas City.”

STOLLER: It was the first big hit. Actually, “Hound Dog” and “Kansas City” were both written the same year, 1952, when we were 19. Yeah, I remember very well both of those songs, the writing of them.

Was “Kansas City” first?

STOLLER: I’m not absolutely sure. I do know when “Hound Dog” was recorded — it was recorded in August, 1952, it came out in 1953. “Kansas City” might have been after that, but it came out in December or thereabouts of ’52. There might not have been as long a wait. Cause I remember –

LEIBER: “Hound Dog,” waiting –

STOLLER: We were waiting and waiting and waiting for “Hound Dog” to come. We knew, if one can know, it was a smash –

LEIBER: In the blues.

STOLLER: In the blues field. We went down to Pico. We went and waited and waited and said, “When will the goddamn thing come out?”

LEIBER: I remember it came out when I was in Boston. Visiting my sister. I think it took eight or nine months to come out. Then it came out, and it was out for twenty hours. And it broke. Like the atom bomb. In Boston. And I found out that it broke every place else within five minutes. It was one of the biggest hits ever.

You wrote that song after you went and heard Big Mama Thornton sing?

STOLLER: In-between seeing her sing and coming back to a rehearsal at Johnny Otis’ house.

You pounded out the rhythm on your old car—

STOLLER: Yeah, on my old car. [Laughs]

LEIBER: A green Plymouth.

STOLLER: It was actually gray. It was a gray 1937… It was greenish gray, you’re right.

And that main line, “You ain’t nothin’ but a hound dog,” just came to you?

LEIBER: Yeah, it did. And I felt it was a dummy lyric. I was not happy. I wanted something that was a lot more insinuating. I wanted something that was sexy and insinuating. And I told Mike I didn’t like it, we were driving, and he said, “I like it, man.”

I said, “I like the song idea, but I don’t like that word. That word is kind of replacing another kind of a word.”

He said, “What are you looking for?”

I said, “Do you remember Furry Lewis’ record “Dirty Mother”?

He said, “Yeah?”

I said, “Well, I’d like to write something like that.”

Mike said, “You’ll ruin it. If you write something like that, they won’t play it.”

I said, “I don’t care if they don’t play it, I want this word in the song.”

He said, “Jer, leave it alone. I think you’re making a mistake.”

STOLLER: Well, I liked “Hound Dog.” I liked the sound of it.

Big Mama Thornton’s version is in E flat. Did you write it in that key?

STOLLER: Didn’t write it in a key. I probably played it in C, cause it was easier.

When you say you didn’t write it in a key, did you write it away from the piano?

LEIBER: The two of us walked in his house, and walked into this sort of a den, where this upright piano was. And I was singing. I started singing it in the car on the way over. “You ain’t nothin’ but a hound dog, quite snoopin’ round my door.” And I didn’t have all the lyrics. And we walked into Mike house, into the den, and he walked over – and I will never forget it, the moment is indelibly etched on my memory – he walked over to the piano, and he had a cigarette in his mouth, and the smoke was curling up into his eye, and he kept it there and he was playing, and he was grooving with the rhythm, and he was grooving, grooving, and we locked into one place. Lyrical content, syllabically, locked in to the rhythm of the piano. And we knew we had it.

We wrote it in about 12 minutes. And I will never forget it. He had the smoke from this cigarette curling up into his left eye, and I was watching him.

And he was singing, “You ain’t nothin’ but a hound dog,” and I said, “Yeah, yeah, yeah – that’s it.”

STOLLER: And we drove back to the rehearsal. Because we had been invited. We had worked with Johnny Otis on a couple of sessions with Little Esther and Little Willie doing duets with Little Esther, and so on. And [Johnny Otis] called me and said, “Are you familiar with Willie Mae Thornton?”

I said, “No, I’m not.”

He said, “Well, I need some songs.” The procedure, before that, was that we’d get a call from Ralph Bass, who was the head of Federal Records, a division of King. He would call and say, “We’re cutting Little Esther tomorrow. 2 to 5 at Radio recorders. Bring some songs.” And we would write 2 or 3 songs. And sometimes during the session, during which we’d try to get some of our ideas done, even though we were just newcomers in that field, we’d go out in the hall and write another one.

So Johnny called and said, “Come over and listen to her and write some songs,” and that’s the way that happened. We went over and heard her and said, “Whoa!” We ran over to my house in my car, wrote the song, came back.

LEIBER: I just remembered – we came back, and I had this sheet of paper. And we walked in. And I think I said, “We got it.” And Big Mama walked over and she grabbed the sheet out of my hand and she said, “Let me see this.” I looked at her and I looked at the sheet. And I saw that the sheet was upside-down. And she was just staring at it, looking at it, as if she could read it, right?

She said, “What does it say?”

I said, “You ain’t nothing but a hound dog, quit snooping round my door.”

She said, “Oh, that’s pretty.” She took the sheet back and she started singing [slowly and melodically], “You ain’t nothin’ but a hound dog…” She’s singing a ballad. She’s crooning a ballad.

And I said, “Mama, it don’t go like that.”

She grabbed the sheet and she said to me, “Don’t you tell me how to sing.” And she started to sing it again. And Johnny Otis had witnessed this little contretemps, and he came over, and he was getting a little bit salty. And he said, “Mama, don’t you want a hit?” And she said yes. And he said, “These guys can get you a hit.

STOLLER: He said, “These guys write hits. Which was –

LEIBER: Not true [Laughter]. He said, “These guys can write you a hit.” She accepted that, and he said something like, “Now be good.” Like he was punishing a child. Then he turned to me and he said, “Why don’t you perform it for her? Why don’t you demonstrate the song?” And I was a little nervous, because there was about a twelve-piece band sitting on a platform – it was a pretty big band – and I was always used to performing a song wherever, whatever, with Mike. He played the piano, I sang the song, no big deal. And I got up to sing the song, and half a dozen of the men – the rhythm section more than anybody else, guitar and drums, bass, whatever – sort of accompanied.

Mike was not playing the piano when I turned around. And he was standing by the piano, smoking. And Johnny Otis said, “What about your buddy?”

I said, “He’ll play in a moment. He’s just getting ready.” And I said, “Mike – play piano.” He was very self-conscious in those days and didn’t like to perform. He was gonna sit it out. And I almost pleaded with him to play the piano.

The groove she was singing was not right. I said, “Mama, it don’t go like that.”

She said, “I know how it goes. It goes like this…” I didn’t know how to deal with this. I said, “Mike, play the piano.” And the groove fell right in, cause he had the groove.

LEIBER: Just a road map. Mike wrote the melody.

And, just to clarify, you wrote the melody apart from the piano – you just sang it?

STOLLER: More or less. Based partially on what he was singing, and how I felt it should do. But it wasn’t written out on a lead sheet and handed to Mama. We didn’t have time to sit down and write out anything.

LEIBER: I think I had the music for the very first line. [Sings] “You ain’t nothin’ but a hound dog…” And Mike picked that up and went with it, and developed the rest of it.

I am amazed you didn’t like the name “Hound Dog,” given that it’s such a classic now–

LEIBER: The line was not what I wanted. Sometimes you make mistakes.

STOLLER: Thank goodness. [Laughs]

That the two of you met each other at the time you did, and that you ended up writing so many great and important songs together, do you attribute that just to good luck, or was it something bigger – was it Providence?

LEIBER: Now I look at it different. 40 or 50 years ago I thought it was Providence. Or just dumb luck that happens to people kind of mystically or magically. But then about eight years ago, my cousin told me that my father was a songwriter – he used to write religious songs in synagogue. And then I thought that Mike’s aunt was a great musician.

STOLLER: That’s something else. It’s a genetic strain. But I think what Paul is asking is something else. Which has to do with – from my point of view – great luck –

LEIBER: That’s because you’re a gambler.

STOLLER: Well, that’s true. But in those days, I think that two white teenagers that loved and knew enough about black music to begin to write it and meeting each other –

LEIBER: Fortuitous.

STOLLER: Absolutely. Because you could have come over, and I could have been not interested in writing with you. I could have wanted to write “Floatin’ down a river on a Sunday avenue.” Or you might have written that kind of a lyric, and I’d say, “What is this? I’m not interested. Bye.”

Do you remember how “Kansas City” came about?

LEIBER: I do remember how that one came about. I don’t remember how a lot of other ones came about, but I do remember about that. There was a blues with a big band that I loved. And it was one of the only blues with a big band that I really cottoned to. There was one song that I really loved, and it was “Sorry, But I Can’t Take You.” “We’re goin’ to Chicago, sorry, but I can’t take you.” I was influenced by that song, and I wanted to have something like that.

So I sang “Kansas City” to Mike like I sang “You ain’t nothin’ but a hound dog.” And Mike said, “Yeah, I like that, but I don’t want just a blues shout. I wanna write a melody to that. I want to write kind of a jazz-blues oriented melody for Basie, or someone like that.”

STOLLER: What I said was that I wanted to play a blues –

LEIBER: With a melody-

STOLLER: With a tune, so that if it’s played instrumentally, people will recognize it as that song.

LEIBER: I said, “I want it to be a blues shout. I don’t want it to have a predictable melody, some jazz melody. I want it to be a blues, I want it to be really raw, I don’t want it to be phony.”

He said, “Well, who’s writing the music, you or me?”

I said, “Well, I guess you are.” So he wrote the music, and it became the big standard that it became.

That’s fascinating. With both “Hound Dog” and “Kansas City,” you had disagreements about the way they should be –

STOLLER: We’ve had a disagreement about everything since 1950. [Laughs]

LEIBER: Our relationship is the longest running single argument in the entertainment business.

You are both the same age – so it’s kind of a sibling rivalry—

You are both the same age – so it’s kind of a sibling rivalry—STOLLER: Absolutely.

So many of the famous entertainment duos, from Martin & Lewis to Simon & Garfunkel, are famous for their fights.

LEIBER: I think out of those confrontations come very good work.

You came up with the idea of Kansas City cause you liked the use of Chicago in the other song, so you came up with another Midwest city? Was Kansas City the first city you considered?

LEIBER: Yeah. I loved the sound of it syllabically. Kan-sas Ci-ty. Chicago was good, but I liked Kansas City better. Because Chicago is halting consonantly-wise. And Kansas City just rolls out.

STOLLER: And Kansas City was the center –

LEIBER: Of jazz, yeah.

STOLLER: Blues and jazz-blues.

LEIBER: Jay McShann. Charlie Parker. It was kind of an homage from us to Kansas City.

STOLLER: Count Basie put together one of his first bands in Kansas City and had the Kansas City Seven, which had Lester Young. So it was that amalgam of blues and jazz. And Joe Turner –

LEIBER: It was a breeding ground for great musicians.

STOLLER: It was a lot of history of that kind of music.

With a song like Kansas City, would you finish the whole lyric before giving it to Mike?

LEIBER: Rarely. It was later on in our career that I got accustomed to writing the lyrics on my own. But even then there would be a line or two that he would help with.

STOLLER: To my memory, it was always like that. Same thing with the music. I would write the music, and Jerry would make suggestions. He’d say, “It doesn’t fit what I’m trying to say” –

LEIBER: Would you change that note? He’d say, “No”—

STOLLER: No! [Much laughter] But eventually things smoothed out. I’d say, “If I have to change it there, I’d have to change it there, well, that could work…”

You once said that “Kansas City” came together like spontaneous combustion –

STOLLER: Even including the argument, I would venture to guess that the whole thing, within 45 minutes to an hour, was complete. Including the argument.

LEIBER: The songs that were tooled and worked on for weeks did not happen that way. “Is That All These Is?” did not happen that way, was not spontaneous combustion. “Hound Dog” was. “Kansas City” was. “Stand By Me” was. “Down Home Girl” was. A lot of things were. A lot of the early blues things would be finished in ten minutes, twelve minutes. At the most, a half hour. But other things – the Peggy Lee songs – took a lot more craft, and a lot more working. And I would spend a lot of time on my own trying to get it right. Because I didn’t want to waste his time with me struggling with a line that could take me a day or two or longer. Jokey songs for The Coasters, like “Charlie Brown” and “Yakkety Yak,” also came quickly, but not as quickly as the blues. They were technically more refined in terms of form. There’s a lot more rhyming. There’s a lot more acknowledgment of structure.

Did you write the melody of “Kansas City” at the piano?

STOLLER: Yes, I did.

It has been recorded so many times, by Joe Williams, Little Richard, James Brown, Peggy Lee, Little Milton. Even the Beatles recorded it.

STOLLER: I didn’t like the Beatles’ record of it because they neglected to sing my melody, the way it was written.

LEIBER: We don’t like the greatest records, the greatest names.

STOLLER: But Joe Williams, and Count Basie, you know –

LEIBER: — were killer.

The original version by Little Willie Littlefield, released in 1952, is in D flat –

STOLLER: Do you have perfect pitch?

No.

STOLLER: Well, you never can tell because sometimes we would record things in one key and then you’d pitch them up or down.

LEIBER: Presley never did that at all. Presley would sing the song in the key that the demo was in. Even if he had to strain his larynx and everything else.

STOLLER: Because he learned them –

LEIBER: In that key.

Though the original “Hound Dog,” by Mama Thornton, was in E flat, and he sang it in C.

LEIBER: That’s because he got the song from Freddie Bell & the Bellboys. He did not learn the song from Mama’s record.

STOLLER: He knew her record, but it was a woman’s song and he never sang it until he heard Freddie Bell & The Bellboys, who had distorted the song so that they could sing it –

LEIBER: Lyrics and music.

STOLLER: Yeah, both. And that’s how he learned it. Though I’m almost positive that Big Mama’s record was in D or E. I know they were playing it in D or E. It depended on the piano in the studio, which might have been out of tune. I’m sure it was D or E. It was Pete Lewis playing that guitar solo. And he had retuned his guitar to what was, ostensibly, a Southern tuning. It was not standard E-A-D-G-B-E. It was tuned differently. So I am also positive – it would think E. And “Kansas City” was probably written in C. Because at that time I used to write a lot of things in C, because it was easy to whip them off that way. And that was done by Little Willie Littlefield. That was the first record. He was a boogie-woogie blues pianist. And it’s possible that it was in E flat. It may be. We taught the song to Little Willie at Maxwell Davis’ home.

LEIBER: He chipped his tooth on the microphone.

But didn’t Elvis know Big Mama’s version of “Hound Dog” ?

STOLLER: He did. But that’s not where he learned it.

LEIBER: He didn’t do her version.

STOLLER: Her version is a woman’s song. It’s a woman’s lyric and she did it in that way. He heard a white group called Freddie Bell & The Bellboys. I learned this later. They apparently were hired as a lounge act in Vegas, and when he walked through Vegas, he heard them doing it.

LEIBER: It was what you heard from him. Ostensibly, it was like an English skiffle shuffle band.

So Elvis got his lyrics from Freddie Bell?

LEIBER & STOLLER: Yeah.

And it was Freddie Bell who rewrote the lyrics?

STOLLER: Yeah. Or somebody did.

LEIBER: I wrote, “You ain’t nothing but a hound dog, quit snooping round my door, you can wag your tail, but I ain’t gonna feed you no more. You told me you was high class, but I can see through that, you told me you was high class, but I can see through that, and Daddy, I know –“

STOLLER: “—you ain’t no real cool cat, you ain’t nothing but a hound dog.” Freddie Bell’s is, “You ain’t nothing but a hound dog, cryin’ all the time –“

LEIBER & STOLLER: “—you ain’t never caught a rabbit and you ain’t no friend of mine.”

LEIBER: Nonsense! He liked the lick, he liked the sound.

STOLLER: She was singing to a man. And he was singing to a dog. [Laughter]

LEIBER: She was singing to a gigolo, to be very precise. Somebody that was sponging off of her. That’s what it was about.

So were you unhappy with the lyric as Elvis did it?

LEIBER & STOLLER: Yeah.

LEIBER: I didn’t like the record, either. Mama’s record was it. Pete Lewis playing that guitar solo, with her screaming her heart out. That was it. And Presley, he did records that we really loved. One of the best records we’ve ever had of a ballad of our’s was “Love Me” (recorded by Elvis). One of the very best. And he did a great job on a lot of songs.

- Jerry & Mike

STOLLER: “Jailhouse Rock.” I mean, that’s great.

LEIBER: But his biggest song of our’s, I think, I feel, Mike does, I think so, too, I can speak for you, was just not up to snuff. It wasn’t up to his standards either, I don’t think.

STOLLER: Well, I think “Jailhouse Rock” –

LEIBER: Is it.

STOLLER: – is at this point, one of the biggest songs. Bigger than “Hound Dog.” Though “Hound Dog” is his signature.

Bigger in what sense?

LEIBER & STOLLER: Sold more.

LEIBER: It’s more famous, too.

STOLLER: It’s hard to say whether “Jailhouse Rock” is more famous than “Hound Dog.”

LEIBER: Not than “Hound Dog,” no. “Hound Dog” is one of the greatest performed songs of all time.

Some people consider it your greatest song. People have said if you wrote nothing other than “Hound Dog,” that would have been enough.

LEIBER: That is, in a sense, true. The point is, though, the record that is celebrated is not the record that should be celebrated. It should be Big Mama Thornton’s record. That’s the way it was conceived, and that’s the way it was written, and that’s more or less, and very much more, Mike’s bag, because the rhythm pattern that Mike played that day on Columbia Avenue is the rhythm pattern that was used for Big Mama Thornton.

Did you produce Big Mama’s record of it?

LEIBER: Just about.

STOLLER: I’ll tell you what happened. Johnny was running the session, but Johnny had played the run-through at his house. He was the drummer. It was his garage. When we went to Radio Recorders to record it, he went to the booth, because he had to make the record, and he was ostensibly making the records. There was no name producer. That word hadn’t come into the lexicon in recorded music yet. So he was making the record, and Jerry said to him, “It ain’t happening.” His drummer was “Kansas City” Bell. Layard Bell.

LEIBER: Bell. You’re right. Again! [Laughs]

STOLLER: And Jerry said, “It’s not happening. And you’ve got to get out there on the drums.”

Johnny said, “Well, who will run the session?”

And Jerry said, “We will.”

LEIBER: It was the beginning of it. Of producing.

STOLLER: And he went, “Okay,” and he went out there and played the drums. We did two takes. The first one was fabulous and the second one was magnificent. [Laughs] And that was it.

And needless to say, everything was cut live. No overdubs –

STOLLER: No. Mono.

So the first time both of you heard Elvis’ “Hound Dog,” neither of you liked it? You didn’t like the words or the sound?

LEIBER: No. Mike was more tolerant than I was. We really didn’t like it.

STOLLER: It was nervous sounding. It didn’t have that insinuation that Big Mama’s record had.

LEIBER: You know what’s strange about it? It’s something that really is sort of an imitation that never really turned out well. It became one of the biggest smashes of all time. And lots of songs and records that we made that were really great never made it at all.

STOLLER: It’s a matter of aesthetics. It’s where you live. And what really gets to you. That’s really the most important thing. And once in a while you do something that you feel is just right, and everybody else thinks so, too. Then you’ve really accomplished something.

Aside from the groove and the lyrics, did you think Elvis, on “Hound Dog,” had a good voice?

LEIBER & STOLLER: Yeah.

And you knew nothing about him when you first heard it?

LEIBER: No. But when we heard him, I think we thought he was an animal. He had a voice, a range, that was unreal.

STOLLER: Animal in the most positive light.

LEIBER: He would go out there. He was like one big champion in the recording studio. We’d tell him we need one more. It was Take 58. And he’d do it. And he’d do it with the same kind of zest and energy as Take One.

STOLLER: He loved. To perform.

LEIBER: That’s when he was really himself. He was very self-conscious. Very, almost always, openly, embarrassed about being anywhere socially or being anywhere where it had to do with his mixing with anybody. He carried his entourage, the Memphis Mafia with him, and they were his family, and they knew him. If he wanted a peanut-butter sandwich with tomatoes on a bagel, they all understood.

STOLLER: [Laughs]

No bagels?

STOLLER: No, I don’t think he ever ordered a bagel in his life –

LEIBER: No, I know.

STOLLER: I know. Orange pop and peanut-butter and banana sandwiches.

LEIBER: But when he was behind the microphone, that’s where he lived. I know that when you worked with him, he would do lots and lots of takes. Did you feel at the time he needed to do that many takes?

I know that when you worked with him, he would do lots and lots of takes. Did you feel at the time he needed to do that many takes?

LEIBER: He was so good, we kept going –

STOLLER: He loved to perform!

LEIBER: — he’d improve. Yeah, you don’t know when he was gonna stop improving. And when you felt he did, and you got Take 25 or 30 and it was good, we’d often go for Take 31. Because we felt it might be greater. And often it would be. So we’d always go for one or two more after he did a great take.

When he was singing in the studio, would he dance?

LEIBER: No. No way. You mean shake his hips? No.

STOLLER: No. But he was constantly singing. Between songs, he would sing a hymn. He would go to the piano and play a few chords and sing a hymn.

LEIBER: “Nearer My God To Thee.” Stuff like that. White Baptist hymns.

STOLLER: He had The Jordanaires with him. And they’d come in behind him. That’s what he wanted to do all the time.

Would he ever play guitar while doing vocals?

LEIBER: No.

STOLLER: Once in a while he’d pick up an electric bass guitar — it was in those days, it wasn’t real electric bass – and fool around with it. But usually he just sang.

Would you give him ideas of how you wanted a song to sound?

STOLLER: We’d demonstrate it as best we could. The feeling. And that’s what we did.

After he did “Hound Dog,” did you like the idea of doing more with him?

STOLLER: Well, we submitted songs. His music publisher asked if we had any other songs that would be good for Elvis. And Jerry thought of this song “Love Me” that we had recorded with this black duet, Willie & Ruth, and then had been picked up and recorded by a dozen other people, including Billy Eckstein. None of them were hits. And Jerry remembered the song, and it was submitted, and he did a fantastic job on it.

So you were happy with that one.

LEIBER: Oh yeah.

STOLLER: Very. And then they asked us to write songs for the movie. We did “Loving You” and then “Jailhouse Rock.” Then we were informed that he wanted us to be in the studio. Because he knew the records that we were making.

LEIBER: He was a fan of our’s. In fact, he was a fan of our’s before he started making records for Sun Records and Sam Phillips. He knew what we did.

To write the songs for the film Jailhouse Rock, I understand you went to New York –

STOLLER: Well, we didn’t go to New York for that purpose. We went to New York because we had started making records for Atlantic Records. And we also had some notions about writing for theater.

LEIBER: Actually, we went to New York because Nesuhi Ertegün had discovered us in L.A. and he liked the stuff we were doing, and he realized that we were making records at that point for our own label with Lester Sill. And were making records like “Riot In Cellblock #9” and other songs. And they used to get very good reviews in the trade papers but they never really sold very much.

STOLLER: Not outside of L.A. Cause we didn’t have any promotion.

LEIBER: Nesuhi approached us and said, “You know, you’re making great records. But you’re not gonna sell them cause you don’t know how to merchandise records.” He asked questions about who we had doing promotion, who we had taking records to the radio stations. We didn’t have anybody doing anything. We thought all you needed was to make a record and send it to 25 or 30 disc jockeys and that was it. Well, of course, that wasn’t it. And he talked to us about going to Atlantic. And I thought of an idea that might work for us. And something I wanted to do very much. And I talked to him about it and he wasn’t sure we could do that, but he thought if we made records for Atlantic, they would put them out and distribute them.

Mike and I finally talked it over and decided to ask the guys at Atlantic to consider us producers since we were in the studio making the records. And in many cases, Mike was making the arrangement. In many cases, I was directing the rhythm section. They fought like tigers to keep us from getting credit on the label. It had never been given to anybody else.

STOLLER: Actually, they came up with the title “producer.” We didn’t invent that title.

LEIBER: How did we get it? I was fighting with Jerry Wexler.

STOLLER: Yes we were.

LEIBER: Or was it just about money?

STOLLER: No! It was about some kind of credit. For making the record.

LEIBER: Oh, I know, I know.

STOLLER: Finally, when they agreed, they came up with the name “Produced by.” Because I would have thought “Directed by” would have been more appropriate.

LEIBER: That’s what I was gonna say right now. That we came up with “Directed by,” and they didn’t buy it for whatever reason. I think it sounded too consummate –

STOLLER: That may have been so. All I remember is saying we wanted credit, and they finally gave in, cause they said, “Man, how many times do you want your name on the record? You wrote the song. We tell Waxy Maxy in Washington, the distributor, we told him you made the record.” [Laughs]

So you were the first official, designated record producers.

STOLLER: As far as I know.

LEIBER: With credit.

STOLLER: Independent record producers.

LEIBER: There was Buck Ram, who was making records for The Platters. He was making records at the same time. I just remembered that. I haven’t remembered that in forty years.

STOLLER: But he didn’t have a producer credit.

LEIBER: There was no credit. There was no credit at all.

Was there any name for the person doing that job?

STOLLER: The A&R man.

LEIBER: But he never got label credit.

STOLLER: That’s true.

LEIBER: The A&R man –

STOLLER: — was a hired –

LEIBER: — producer, actually.

STOLLER: In effect, a producer. But in some cases, they selected the song. Then they called the take numbers. They hired an arranger, and frequently that was it. They hired an arranger, and they selected a song for the artist. What we were doing, because we were writing and we wanted to protect the intention that we had when we wrote the song, was outline – not only teaching how to sing, which Jerry frequently did by demonstrating over and over certain phrases, and I would write and arrangement, and frequently I would play the piano on those early sessions. I played on all of those Coasters records –

LEIBER: Nobody could ever play like Mike could. And there were wizard piano players. But they never got the feel.

STOLLER: I was not a wizard piano player. I’m still not. Apparently I had the feel for the songs that we were writing. Especially at that time.

I never understood why the name ‘producer’ for records was chosen, as a record producer, of course, is much different than a movie producer.

STOLLER: It should have been `director.’

LEIBER: That’s why I came up with `director.’ I was looking for a word they might accept. And then they refused to use the word ‘director.’ I put a lot of pressure on Jerry Wexler. And to some degree we both intimidated him. We got to a point where we more or less stood our ground and we indicated that if we couldn’t get a credit and a royalty – we wanted a two cent royalty – they didn’t want to give us either, but then they gave in, and we got the royalty –

STOLLER: They gave us a royalty?

LEIBER: It wasn’t two cents?

STOLLER: It was two cents, but then after that we wanted three. And we went up to three.

LEIBER: Mike is right. And they gave us producers credit. And we went from there.

STOLLER: And we made their first million-selling single, which was “Searching” and “Youngblood” [performed by The Coasters].

LEIBER: “Searching” was designed to be the b-side and it became a big hit. “Youngblood” was a big hit, too, but nothing compared to “Youngblood.”

And you would completely produce the sessions-

STOLLER: Between the two of us –

LEIBER: Between the two of us we did everything.

STOLLER: Including the mastering. In fact, even before there was multi-track, we were doing overdubs. When we had to. And cutting an ‘s’ off a word because it wasn’t supposed to be there. Because in those days you couldn’t reach into one track and adjust it. There was only everything.

LEIBER: We used to do it with [engineer and producer] Tommy Dowd, who was a wizard, at Atlantic.

STOLLER: Well, first we did it here, with [engineer] Bunny Robine. At Master Recorders.

LEIBER: On Fairfax. Right across the street from my high school.

STOLLER: But with Tommy, we had a major advantage, because Tommy had –

LEIBER: — a four-track machine.

STOLLER: Eight.

You had eight-track?

LEIBER: Not the first one.

STOLLER: Yeah. Guarantee it. Three people had an eight-track machine. Tommy Dowd, Les Paul and the U.S. Navy.

LEIBER: I remember that Tommy had, by himself, a four-track machine for six or eight months, and then he graduated to an eight-track machine.

STOLLER: Well, when I worked with him, that I recall, he had a small studio – 234 West 56th Street, top of an old brownstone building. My memory of it was that working there with The Coasters was with an eight-track machine. But we didn’t do any of that stuff where you start with the bass and drums and then add a guitar. We did everybody at the same time, but we had the ability to make little adjustments. And we had the ability to have the group, or the lead singer, sing four or five bars, or do a whole performance again. We’d pick the best stuff.

But you wouldn’t overdub the lead vocal, you would do it live.

STOLLER: Oh absolutely, it would have to be.

It’s surprising to me you had eight-track so early on. The Beatles, at Abbey Road, didn’t get eight-track till 1968.

STOLLER: We didn’t except if we worked with Tommy Dowd in New York. He had an eight-track machine early. I’m talking about, I think, 1958. And there was an eight-track. Like I said, there were only three at the time. Tommy was a genius.

You said that you overdubbed prior to having a multi-track?

STOLLER: Yes. Going from a mono to another mono. The original tape, with whatever was on it, and adding a new element.

And it sounded okay?

STOLLER: Well, it wasn’t fabulous. But we got what we wanted!

I read that when you were asked to write the songs for Jailhouse Rock, you were in a fancy hotel in New York, and you spent the nights partying and clubbing rather than write the songs –

LEIBER: It wasn’t a fancy hotel. We were in a small hotel, and Mike was a real jazzaphile, jazznik, and he schlepped me all over New York to small clubs to watch jazz players, the greatest jazz players, and Mike was excited about the whole scene, and couldn’t care less –

STOLLER: But we were given a script. By Gene Auerbach, who said, “We need songs for the new movie.” I forget what the movie was called then. Somebody told me this that the original title was Ghost of a Chance. We kind of tossed it in the corner with some other magazines, and we were having a great time in New York.

LEIBER: And then they came looking for us.

STOLLER: Yeah, Gene came. [Laughs] And he locked us in, more or less. [Laughs]

LEIBER: He came over to lecture us on fidelity in delivering work, and we hadn’t done anything. And he came over and he stalked around the room, and he talked about the necessity of being on time, etc. And finally he shoved the sofa against the door. And he stretched out on the sofa, and said, “Boys, I’m gonna stay here until you give me the score.”

We wrote four songs, and one was “Jailhouse Rock.”

STOLLER: The others were “Treat Me Nice” and “You’re So Square (I Don’t Care)” and “I Want To Be Free.”

LEIBER: We wrote those songs in about three hours, all four of them.

STOLLER: And then we wanted to get out.

LEIBER: He finally took the songs and said, “Great!” and left. And we split.

STOLLER: [To Leiber] Let me ask you a question: Did we make demos of those songs?

LEIBER: I think you played them live, and taught Presley directly, cause I don’t remember a demo.

STOLLER: That’s what I thought! I played them and you sang. Cause I don’t remember –

LEIBER: Yeah, I remember. And I’ll tell you where the piano was. It was in the right hand corner.

STOLLER: I remember you and I teaching Presley the songs.

LEIBER: Some session was over. I think it was the Jailhouse Rock sessions, and one of the guys in the entourage of mechanics and doers and co-producers and associates came over to me and said, “Jerry, we’d like you to show up tomorrow at 7:00 in the morning. We’d like you to play the piano player in the film.” And I said, “But I’m not a piano player. Mike is the piano player.” “That doesn’t matter. You look like a piano player.”

STOLLER: You look like one. [Laughs]

LEIBER: What nonsense. So I go home that night, and my 10:00 that night, my face was swollen out to here – I have an impacted wisdom tooth. So I call Mike up, and I said, “Mike, you’re gonna have to go at 7:00 in the morning. They wanted me to be the piano player.” He said, “Jerry, I can’t do it. I have a beard.” I said, “So shave it!” He said, “No.” He’s always like that.

STOLLER: I’ve got to protect myself.

LEIBER: He was, “How do you want your ‘No,’ fast or slow?” But then he said, “Alright, I’ll do it.”

STOLLER: I didn’t say that to you about the beard. You said, “They won’t know the difference.”

LEIBER: I said, “Yes they will! Shave your beard off!”

STOLLER: No, no. My memory is this. Your memory could be right, but mine could be righter. I went over and they put me in a Hawaiian shirt, and they said, “You start Monday morning, 7:00 in the morning every day.” And they said, “Shave the beard off, it’s a scene stealer.”

And you did?

STOLLER: I did.

LEIBER: The dialogue is a little different from how I wrote it.

STOLLER: Yes, but the result was the same. And that was my debut!

LEIBER: He became a star, and I became a no-name schlepper.

I had assumed “Jailhouse Rock” was the original title of the film, and you wrote your song to the title. But you invented that title.

STOLLER: There was a scene. We didn’t read the script that carefully, but we thumbed through, and Jerry saw that there was an amateur show in a prison. So he wrote “Jailhouse Rock.”

STOLLER: The only title song we wrote to their title was “King Creole.”

Good to set the record straight. It’s been written that you wrote the songs for the movie Jailhouse Rock –

STOLLER: We wrote songs for the movie that became Jailhouse Rock.

It’s was written you were staying in a “ritzy hotel.”

LEIBER: Ritzy?

STOLLER: No, it wasn’t.

LEIBER: The Gorham Hotel.

STOLLER: The Gorham Hotel.

LEIBER: Did they mean fancy, expensive?

Yes. Fancy like The Ritz.

STOLLER: No.

LEIBER: The Plaza was ritzy. The Waldorf was ritzy. They don’t pay expenses when you do movies.

When you wrote “Jailhouse Rock,” did you have a sense that it was a great song?

LEIBER: No, we never felt that. See, you can write a great song and you can end up with a lousy record. Because record production is sometimes not up to speed. As Mike once said, “We don’t write songs, we write records.”

STOLLER: [Laughs] He’s giving me the credit for saying that.

Yet you produced many of the records yourself, so you ensured the songs would become good records.

LEIBER: We started producing in self-defense, because a lot of our songs got wrecked. And we started moving closer and closer to having hands-on producing situations. We were the first independent producers.

In what ways were your songs wrecked? Was it the wrong feel?

LEIBER: Yeah. You give an A&R man a song, and he’ll misinterpret it. It’ll be like a Texas shuffle, and he’ll do a Benny Goodman swing arrangement of it, instead of Tiny Bradshaw or James Brown, or the right stuff.

So with “Jailhouse Rock,” you both wrote words and music simultaneously?

LEIBER: Yeah. Most of the blues were written that way. Once I had a couple of lines, it created a groove. And once the groove was in, he could groove with it and extend it, if he wanted to, and that’s the way a lot of the blues were written. The cabaret songs were not written that way.

STOLLER: On some ballads, sometimes it would start with a melody. A beginning of a melody. Then the words would come in. In the early days we worked a lot –

LEIBER: Simultaneously.

When you wrote all four of those songs in a handful of hours, did you feel there was something phenomenal about that?

LEIBER: No. “Hound Dog” was twelve minutes.

STOLLER: We wrote songs for Little Esther when a phone call came. As Sammy Cahn would say: “What came first, the music or the lyrics? The phone call.” We would write three songs in a few hours, and finish one in the car on the way to the studio.

LEIBER: Tell the story about the Christmas song.

STOLLER: Oh yeah. [Laughs] They were doing a Christmas album with Elvis, and he wanted us in the studio all the time.

LEIBER: Like lucky charms. He believed that. We were lucky charms.

STOLLER: We were in the studio and they said, “We need another song.” And we went out into the utility closet at Radio Recorders and within eight to ten minutes we had written “Santa Claus Is Back In Town” –

In the closet.

STOLLER: Yeah. And, pardon the expression, we came out of the closet – [laughs].

LEIBER: Well, he did, not me. As you can see, I stayed in the closet.

STOLLER: And we came in with the song. Colonel said, “What took you so long, boys?”

So again, no instrument. You just wrote the melody in your head.

STOLLER: Well, yeah. It’s kind of a vagueish melody.

LEIBER: It’s also blues oriented. And Michael would often, in a song like that, add sort of a touch of polish of a melody.

STOLLER: Well, we sang it to them.

Many songwriters have written great songs fast, but to write four great songs fast –

LEIBER: They’re not all great.

STOLLER: We’ll let you decide which ones are and which ones aren’t.

Do you think it was the pressure of having to write that enabled you to come up with four songs so quickly?

STOLLER: No.

LEIBER: No.

Because the Motown writers and the Brill Building writers had that kind of pressure, and they came up with great stuff.

STOLLER: Well, the Brill Building writers – and they didn’t write in the Brill Building, as you know (1619 Broadway) but across the street at 1650 Broadway – they had to compete with each other for cuts.

As did the Motown writers.

STOLLER: I guess so. We didn’t compete with anybody. We chose our own productions. The only time we wrote for assignment was when we wrote for movies.

When you would teach a song, such as “Jailhouse Rock” to Elvis, would he do the song pretty much as you did?

STOLLER: No.

LEIBER: I don’t remember him copying me behind a microphone. I remember him going behind a microphone, and what he did for the first two or three minutes was crack bad jokes.

STOLLER: He had one of his entourage, also –

LEIBER: — on the microphone.

STOLLER: — comedian. Talking like a phony airport —

LEIBER: “Boarding on a 707, gate twelve…” And they all laughed. [Laughter]

STOLLER: And they ate lunch in the studio, too.

LEIBER: He was right about that. Peanut Butter and banana sandwiches. The idea made me ill.

STOLLER: That was amazing to us. We were producing records. And we would go into the studio with the Robins or with the Coasters, and we had to get four tunes done in three hours.

LEIBER: It was the union’s rules.

STOLLER: Because, what was it in those days? Four dollars and 25 cents per musician, and if you went overtime, you know, that was heavy. These guys took over the studio. RCA booked the studio from 10:00 in the morning till whenever… They just blocked out the whole week! So they stayed in the studio, and nobody was worried about them.

LEIBER: That was the only pressure, actually, that we put on ourselves. Because we were just trained, we were brainwashed, not to go over three hours. And to get four sides. And we always did. And we learned how to move very quickly and very effectively. But that’s the only pressure. The other pressure didn’t exist for us.

STOLLER: No. First of all, we were very young, and we could work 18 hours a day without being concerned about anything, about being tired—

LEIBER: And smoke four packs of cigarettes.

STOLLER: And drink endless cups of tea.

LEIBER: Can I ask you a question? Why are you so interested in “Jailhouse Rock”? Is it that important?

Yes, it is. It’s part of our culture. It’s one of the most iconic and classic songs performed by Elvis, who is considered the king of rock and roll. When you hear that record, he is alive – his spirit is alive in that performance.

LEIBER: Yeah, that’s him.

STOLLER: Absolutely. That’s true.

STOLLER: Well, it wasn’t part of it. What happened – this is my memory, again. Which is pretty good – Jerry presented me with spoken vignettes. And I set them to music. They were all set to the same music. And Georgia Brown, the British singer-actress who had been on Broadway in the show “Oliver,” she came over with her –

LEIBER: Manager.

STOLLER: Her manager, and an arranger. Peter Matz. And we played this for her, and she said, “It’s great, it’s great. But it’s all talking, I need something to sing.” And we had this other refrain, “we all wore coats with the very same lining,” and we stuck it in and she said, “That’s it. I’m gonna do that on my television special in London on the BBC.” She left and we looked at each other, and said, “This doesn’t make any sense.” [Laughs] We both vowed to write a refrain – he the lyrics and me the music.

The next day I called him and said, “I’ve got a tune that I think is really right for this.”

And he said, “Okay, but listen, I’ve written a lyric already. And I know that the lyric is right. And you might have to jettison what you wrote.” I came over and I insisted on playing and he insisted on reciting, and finally I won, and I played it. The tune.

And he said, “Play it again.” And I played it, and he sang the lyric. And it fit perfectly. We didn’t have to change anything.

Amazing.

LEIBER: That is pretty amazing, yeah. That only happened once in 56 years, but it happened.

STOLLER: And there’s only one rhyme in the entire piece. “Let’s break out the booze and have a ball, if that’s all… there is.” That’s the only rhyme in the piece.

LEIBER: No.

STOLLER: No, no, not at all. [Laughs]

Many songwriters have said they don’t feel they write songs, but that songs come through them. Lennon said that –

LEIBER: He got that from me. That’s you’re a vessel.

You feel that?

LEIBER: Sometimes.

Had you ever written a song like “Is That All These Is?” before – a song with spoken vignettes?

STOLLER: We wrote “Riot In Cellblock #9” that has spoken parts. It’s very different. That’s talking blues.

LEIBER: That’s talking blues.

STOLLER: And this was not exactly talking blues. And yet –

LEIBER: It was Sprechstimme, it wasn’t blues at all.

STOLLER: I know it’s not blues –

LEIBER: The closest thing you can get to a model for it is Bertolt Brecht, and that kind of articulation. It’s in “The Black Freighter”–

STOLLER: But Sprechstimme is almost –

LEIBER: Tonal –

STOLLER: Tonal. This is just a recitation. It’s not even implied to be sung.

LEIBER: Yeah. I tried it. I tried kind of a dummy tune, and I realized that the tune created a synthetic kind of unreality that is so far from the tough attitudes about living I was trying to express. So I decided to try and just say it. But I was afraid to do that, because I didn’t think it would be acceptable.

STOLLER: When I set it to music, not having really discussed it at length with you at that point, I said, “You know, I think these should really be spoken,” and you said, “Of course, that’s what I meant.”

A lot of people have likened it to Brecht and Weill.

STOLLER: We were influenced by Brecht and Weill because we liked their work.

LEIBER: I was influenced by a long short story by Thomas Mann. Called –

STOLLER: “Disillusionment.”

LEIBER: “Disillusionment.” And I decided – all of these decisions came at about the same time – both Mike and myself were getting tired of writing for the market. And also the market was changing to a point where a lot of stuff that we liked to write was not going down, was not happening. A lot of the groups from England were happening, a lot of that other stuff was happening, Kennedy got killed. And the stuff we were doing was kind of fading from the scene. And we both wanted to write some material that was more adult and more theatrical.

So I was reading this story by Mann, and the thread in it was this kind of terrible, negative thing. But it had, at the same time, a parallel line that was very Germanic and very funny. So I felt I’d like to try to translate this material. At least the feel of it, the sense of it. And I wondered if it would work. And I did a lot of work on the lyric, and I gave Mike the material. And we usually always, as you know, worked together, on whatever we were doing, simultaneously, and on this piece I just handed him a lyric –

STOLLER: The original, the vignettes, you handed me on a piece of paper.

LEIBER: I gave him the song, and he took it home. And he had written, on his own, without lyrics, a refrain. And I came in the next day, and we hassled over who would play it first.

I said, “Let me play it first, because then lyrics come first before the music.”

He said something like, “Not in this case,” and it was another argument.

Then he played the melody. And I was in shock. [Sings refrain]

STOLLER: I wanted to play it first, because I thought he would love it. And I wanted to play it so he would be inclined to adjust his lyric to it, rather than me having to tear my beautiful new tune apart to his lyrics. I wanted to get there first for that reason. But fortunately, neither of us had to adjust.

The lyric is so beautifully constructed –, with the repeating refrain tying together disparate subjects: first a fire, then the circus, then love, and then life —

LEIBER: That last one is suicide. “If that’s the way she feels about it, why doesn’t she just end it all? Oh, no, not me.” Oh, you want another secret about that? In Peggy Lee’s version she sings, “If that’s the way she feels about it, why doesn’t she just end it all? Oh no, not me, I’m not ready for that final disappointment.” Which is wrong. And which changes to some degree the meaning of the song which was intended. By one word. And that’s a great lesson in writing anything. One word can change it quite a bit. And that is, “If that’s the way she feels about it. Oh no, not me, I’m in no hurry for that final disappointment.” Which is the joke. I’m not ready for that final disappointment – is not a joke.

But she insisted on singing ‘ready,’ because I think she felt that it founded more natural. And she missed the point.

Interesting you started the song with a description of a fire, which can be both beautiful and disastrous –

LEIBER: It can be very dangerous and uncontrollable.

What brought you to start there?

LEIBER: I never know what brings me to think of anything. I’m not one of those writers who gets an idea from looking at something. The words, the ideas, I don’t know where they come from.

STOLLER: We made a demo of it, and Jerry brought it to Peggy. She said, “This is my life story.” She said, “I was in a fire like that.”

LEIBER: She said, “You wrote this for me. I know it. And if you give it to anyone else, I don’t know what I’m gonna do.” And she was convinced, on some mystical level, she wasn’t joking, she thought that was true.

It is a perfect song for her.

LEIBER: But we really wrote it for Lotte Lenye.

STOLLER: Oh, that’s a lotta Lenya… [Laughter]

LEIBER: I like that.

STOLLER: You got it. [Laughs]

LEIBER: Leslie Uggams recorded it first. Mike wanted to test the arrangement out, really, that’s the truth. We both knew that she wasn’t really appropriate. But we couldn’t get anybody –

STOLLER: But we didn’t have anybody ready to record it.

LEIBER: Yeah, some record. I would have done it with Mae West. In fact, she made a record for us. She did the Elvis Presley Christmas song that we told you about.

STOLLER: “Santa Claus Is Back In Town.”

LEIBER: And it’s pretty good.

STOLLER: It’s funny. [Imitates her] “Christmas, oh… Christmas, oh…” That’s the way it starts. [Laughs]

LEIBER: I love the record. That’s one of my favorites. And of all the “Kansas City” records, out of all those great stars – Little Richard, Joe Williams, you name it. I think the best take is Little Milton. You’ve got to hear it.

STOLLER: For me it’s Joe Williams.

LEIBER: Well, I mean, it’s Joe Williams for me, too.

What was it about the Joe Williams record that made it the best?

LEIBER: It’s really what it oughta be.

STOLLER: The intention. It was, finally, the intention of a real kind of Kansas City blues-jazz feel.

LEIBER: It was stylistically perfect. A lot of people who did it before did it as kind of a country, semi-country version, semi-big city blues. Tiny Bradshaw.

STOLLER: Or dropped most of the tune and just shouted.

STOLLER: Well, the Beatles copied Little Richard’s record. The Beatles’ version is good, but it isn’t what I wrote. It doesn’t have the melody that I liked.

And he said, “Yeah, yeah, I can see that.” He said, “I’ll pick up the phone and call Teddy Reig at Roulette Records,” because Teddy Reig produced all of the Basie stuff there at Roulette. So he placed a call – it was a Friday, I think – and left a message.

And Monday the trades came out, and they had a pick. And the pick was “Kansas City” by Wilbur Harrison. Plus three other cover records mentioned. And we had not had a cover in seven years. We were just thinking of the song [laughs] and on Monday, it came out as the big pick hit of the week. And this is after seven years.

LEIBER: And that was a big hit. It went to Number One. I still can’t figure it out.

STOLLER: He remembered the song, Little Willie’s record. Which was originally called “K.C. Loving,” though the lyrics were the same. And I always thought Ralph Bass screwed up the possibility of a hit by calling it “K.C. Loving” instead of “Kansas City” because he thought it was hip.

Of all the great writers of classic rock and roll songs, such as Little Richard and Chuck Berry, there’s not one who also has written songs like “Is That All There Is?” Your stylistic range is amazing.

LEIBER: Well, it’s obvious that we’re just geniuses. [Laughs]

I know you’re joking, but it’s true.

STOLLER: He’s not joking.

So you wrote the melody for the refrain of “Is That All These Is?” as just pure melody, with no lyric idea at all?

STOLLER: That’s true. But I knew the subject matter from the vignettes. Each one of which ends with “Is that all these is…” And although I didn’t specifically, consciously, write the melody as “Is that all there is” –

LEIBER: He wasn’t writing to a lyric, he was just writing notes that obviously sounded –

STOLLER: That felt right to me.

LEIBER: And I came in with the lyric, syllable for syllable.

And it actually matched perfectly – you didn’t have to change a single word?

LEIBER: Not at all.

That’s amazing.

LEIBER: It is amazing.

On the song “Stand Be Me,” Ben E. King has writing credit with you. Did he write it with you?

On the song “Stand Be Me,” Ben E. King has writing credit with you. Did he write it with you?STOLLER: Yeah.

LEIBER: Yes.

There’s been countless instances of singers getting their name on a song without really writing it, a tradition that dates back to Jolson and certainly extends to modern times.

STOLLER: There has been, but not in this instance.

LEIBER: We were scheduled to have a rehearsal with Ben E. King, and Mike and I got there early, and a couple of other guys were in this rehearsal –

STOLLER: I have a totally different memory. Go ahead.

LEIBER: — were in this rehearsal hall. We had a small auditorium in a junior high school with a piano. Ben E. came in and “Hi, hello,” you know. And he said, “Hey man, guess what? I wrote a song.” Ben E. was not a songwriter. A very good performer, but not a songwriter. And he went [sings softly, to the tune of “Stand By Me”], “When the night has come and the land is dark and the moon is the only light we’ll see… I won’t cry, I won’t cry…” He said, “That’s all I wrote.”

I said, “That’s pretty good. You want me to finish it for you? You want me and Mike to do it?”

He said, “Oh, yeah, man, that would be great.” So Mike and I finished it. And Mike put that incredible bass line on it. And when I heard that bass pattern, I said, “That’s it. That’s a hit.” And I didn’t do much predicting of hits. But I knew that was in there. I also knew “Hound Dog” by Big Mama Thornton was a hit. And “Kansas City” by Wilbur Harrison. Which I wasn’t crazy about, but I knew it was a hit.

And we started writing “Stand By Me.” And it became what it became.

Did the two of you take it away from Ben E. and work on it on your own?

LEIBER: No, we finished it right there. Like we did most of the stuff. We did it there. I mean, these were not assignments that you took home and worried over for a week or two or three or a month. These were hot off the griddle, and we always felt that way, that when they were hot they were more effective and more attractive.

So he had a melody and lyrics.

LEIBER: He had the first few lines and the beginning of a melody.

Did he have the chorus?

LEIBER: Yeah, I think he did have it. Because it was only one phrase, one line. But he said he couldn’t get the rest of the lyrics. He’s not a songwriter, but he came up with something pretty good. A couple of sentences and a hunk of the refrain, or maybe all of the refrain.

STOLLER: As I remember, it was in our own office. We had an office on 57th Street. And Jerry and Ben E. were fooling around with the lyric on “Stand By Me.”

LEIBER: And then you came up with the bass pattern.

STOLLER: And I came in. Ben E. was singing it in the key of A. And I sat down at the piano and I just felt this bass pattern, and I started working on a bass pattern, and within five minutes I had the bass pattern, which is the bass pattern of the song, and is a big part of it. And in the orchestration, it starts with bass and guitar, and it goes into strings playing it, and it builds up, and this pattern is from beginning to end. But Jerry was working with Ben E. on it, and I think most of the melody of the tune is Ben E.’s. I wrote the bottom part. Which is kind of a signature of the song.

LEIBER: The bass pattern.

STOLLER: [Sings bass line]. “Boom-boom, boom-boom-boom, boom, boom-boom-boom, boom…”

It’s in A, and has that beautiful shift of chords to the VI chord, the F#minor – did you invent that, or –

STOLLER: It’s kind of implied. I thought it, to me, it was implied. I think the melody may have shifted a little with the chords I was using. But it’s basically his.

And he was just singing it a cappella?

STOLLER: Yeah.

John Lennon, years later, made a famous record of it. Also in the key of A. Did you like his version?

STOLLER: Yeah. It was a different kind. But it still had the bass pattern. It wasn’t like the difference between Big Mama and Elvis. It was the same song, it just had a very different feel. But it was legitimate. It felt right. It felt good, also.

LEIBER: It was too fast.

Lennon’s was too fast?

LEIBER: Yeah. It felt too fast.

STOLLER: It was stiffer. It was definitely a stiffer feel.

LEIBER: Ben E.’s was more syncopated.

LEIBER & STOLLER: [Sing rhythmic bass patterns of both in unison, in which Lennon’s is straight-time, and Ben E.’s is more fluid and syncopated.]

STOLLER: That’s really the difference.

LEIBER: Unison! Did you hear that unison?

STOLLER: It felt good, I like it.

LEIBER: It felt white. That’s what we’re trying to say. And as Mike said, it’s somewhat stiffer. It doesn’t really have that loop in it.

“Stand By Me” is a phenomenal song. It’s got a beautiful melody but it’s also visceral. It’s a rock song but it’s a ballad. It’s got everything.

STOLLER: But, you know, it was a hit when it came out. But when it came to be this wedding song and this everything song is when Rob Reiner made this movie.

I met Rob at a party, and he insisted on singing all of the Leiber & Stoller songs. And he insisted I go to the piano while he sang. And he called me up months later and said, “I have this movie. It’s called The Body. And it’s been in the can for a while, and I like it. The Body is the right title for it. But it’s not good, because it’s based on a short-story by Stephen King, and people will think it’s a horror film. It’s really a coming-of-age movie. So I want to call it `Stand By Me.’”

I said, “Great! Be my guest.”

And then I thought about it and I called him back. This was 1986. The record came out in ’61. And I said, “Hey, who do you think we can get to record it and put it into your film?”

And he said, “We talked about that. But I view this movie as a period film. So I’d like to go with the original record.”

I said, “We produced the original record.” So it wasn’t that I wasn’t flattered, but it was that I thought that, well, this’ll be an album cut, and if we got Tina Turner [laughs], or somebody else to do it, it might become a hit. And it did become a hit again. The same record. Nothing was done to it.

LEIBER: I couldn’t make heads or tails out of that choice. I thought it had nothing to do with that movie at all. And I still think so. I think he was in love with the record and the song, and –

STOLLER: Hey – listen –

LEIBER: – and he wanted it in his movie. And the movie was about a dead body in the woods. And what does “Stand By Me” have to do with that, with children in the movie, what –

STOLLER: Whatever it is, I am so grateful to him. Because it became –

LEIBER: Yeah. A monster hit.

STOLLER: I think people liked the song [when it first was released], but it didn’t become that powerful. It became a much bigger hit 25 years later. Which is really great. I mean, five years, maybe. But 25 years?

Donald Fagen did a version of your song “Ruby Baby” –

STOLLER: Yeah, I love that arrangement.

He took your chords and extended them

LEIBER: Yeah. And he did a terrific job. The original “Ruby Baby” was – Dion.

STOLLER: No, Dion’s wasn’t first. The first was The Drifters. Nesuhi Ertugun recorded it in 1954. But I love Dion’s record. And I love Donald Fagen’s record. [Claps syncopated drum rhythm from the Dion record.]

I’d like to ask you about the song “Spanish Harlem.” The story goes that Phil Spector wanted to write a song with you for a long time, and he came over and had a chord pattern which he played you —

LEIBER: No. He didn’t have anything.

What happened is that Phil had bothered me for three months, four months, to write a song with him, and I didn’t want to do it for a couple of reasons. And the main reason is that Mike and I had sort of a tacit understanding that we were exclusive partners. A number of people wanted to write with Mike and a number of people wanted to write with me, and we just didn’t. And [Phil] wanted to write with me, and he was signed to us. Lester Sill [their music publisher] sent Phil Spector to us. For safe keeping. Did a bad job. Lester called me up one day, and said, “Jer, I got a kid out here who’s really talented. And he’s nuts about you guys, he worships the ground you walk on.”

I said, “Well, be careful, watch out. That’s usually dangerous. Why do you hate me so much? I never did anything to you.”

He said, “He wants to come out and work for you guys.”