Part II.

By PAUL ZOLLO

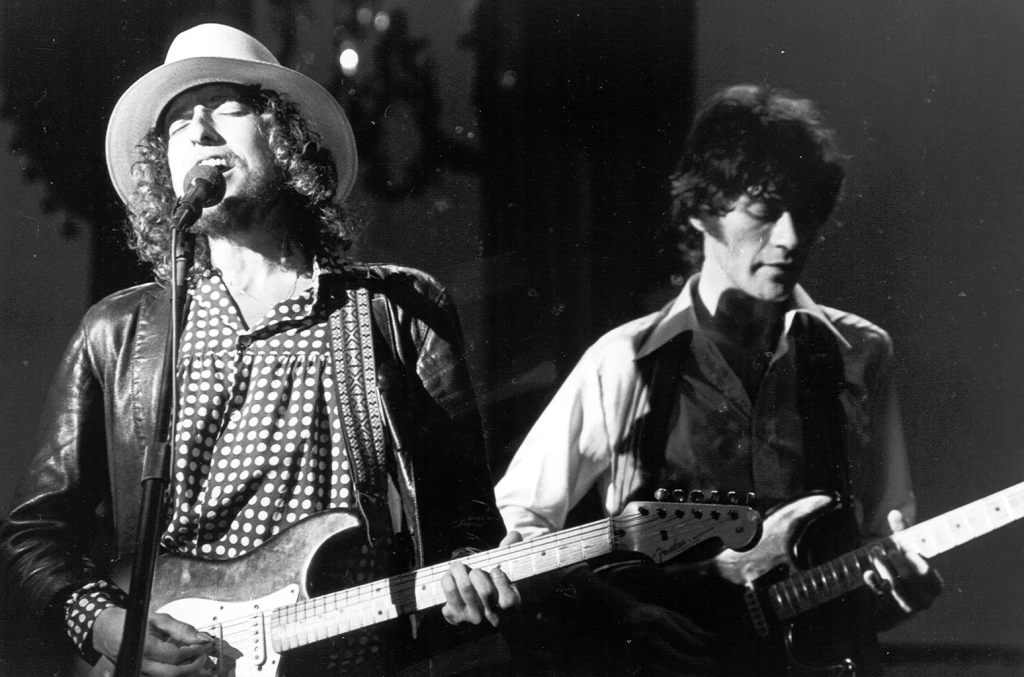

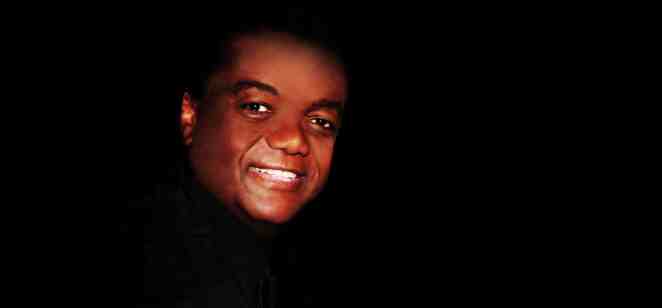

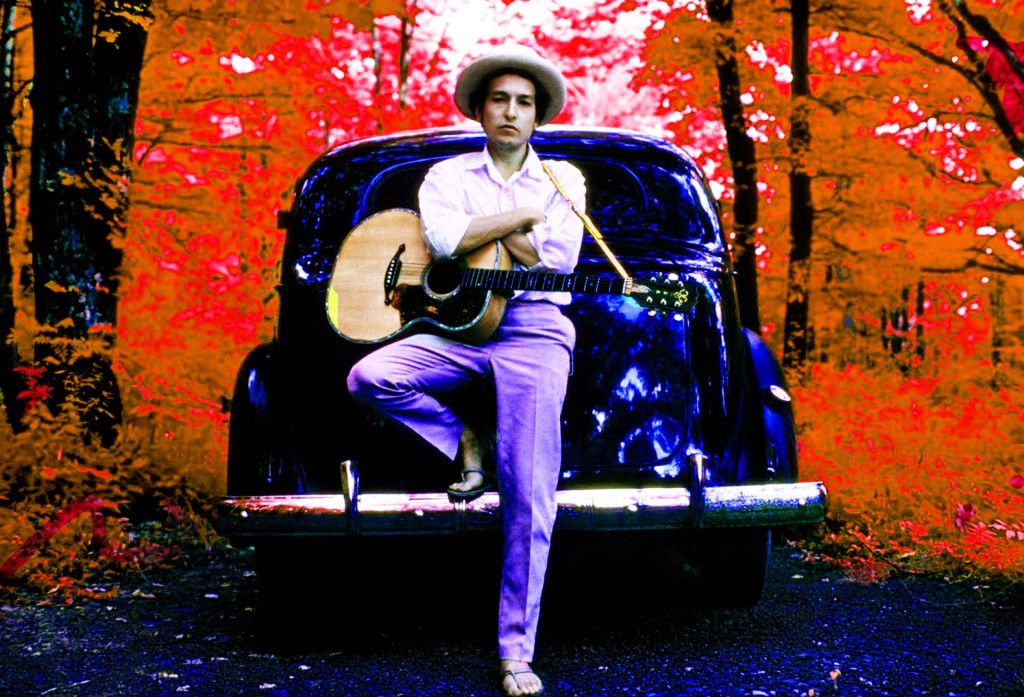

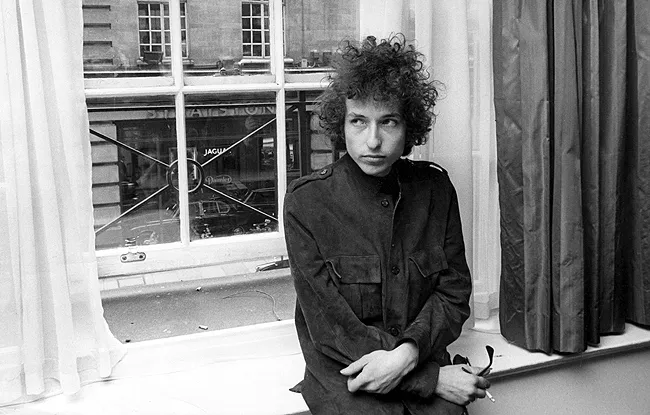

This is the second half of the interview with Bob Dylan conducted by Paul Zollo in 1991 at the Beverly Hills Hotel. Originally published in SongTalk, the journal of the National Academy of Songwriters, and included in the book Songwriters On Songwriting by Paul Zollo, and Rolling Stone’s Essential Dylan Interviews.

Zollo: Would it be okay with you if I mentioned some lines from your songs out of context to see what response you might have to them?

Dylan: Sure. You can name anything you want to name, man.

Zollo: Thanks. Here goes: “I stand here looking at your yellow railroad/in the ruins of your balcony… [from “Absolutely Sweet Marie”]

Dylan: [Pause] Okay. That’s an old song. No, let’s say not even old. How old? Too old. It’s matured well. It’s like wine. Now, you know, look, that’s as complete as you can be. Every single letter in that line. It’s all true. On a literal and on an escapist level.

Zollo: And is it truth that adds so much resonance to it?

Dylan: Oh yeah, exactly. See, you can pull it apart and it’s like, “Yellow railroad?” Well, yeah. Yeah, yeah. All of it.

Zollo: “I was lying down in the reeds without any oxygen/I saw you in the wilderness among the men/I saw you drift into infinity and come back again…” [from “True Love Tends To Forget”].

Dylan: Those are probably lyrics left over from my songwriting days with Jacques Levy. To me, that’s what they sound like.

Getting back to the yellow railroad, that could be from looking some place. Being a performer you travel the world. You’re not just looking off the same window everyday. You’re not just walking down the same old street. So you must make yourself observe whatever. But most of the time it hits you. You don’t have to observe. It hits you. Like “yellow railroad” could have been a blinding day when the sun was bright on a railroad someplace and it stayed on my mind. These aren’t contrived images. These are images which are just in there and have got to come out. You know, if it’s in there it’s got to come out.

Zollo: “And the chains of the sea will be busted in the night…” [from “When The Ship Comes In”].

Dylan: To me, that song says a whole lot. Patti Labelle should do that . You know? You know, there again, that comes from hanging out at a lot of poetry gatherings. Those kind of images are very romantic. They’re very gothic and romantic at the same time. And they have a sweetness to it, also. So it’s a combination of a lot of different elements at the time. That’s not a contrived line. That’s not sitting down and writing a song. Those kind of songs, they just come out. They’re in you so they’ve got to come out.

Zollo: “Standing on the water casting your bread/while the eyes of the idol with the iron head are glowing…” [from “Jokerman”].

Dylan: [Blows small Peruvian flute] Which one is that again?

Zollo: That’s from “Jokerman.”

Dylan: That’s a song that got away from me. Lots of songs on that album [Infidels] got away from me. They just did.

Zollo: You mean in the writing?

Dylan: Yeah. They hung around too long. They were better before they were tampered with. Of course, it was me tampering with them. [Laughs] Yeah. That could have been a good song. It could’ve been.

Zollo: I think it’s tremendous.

Dylan: Oh, you do? It probably didn’t hold up for me because in my mind it had been written and rewritten and written again. One of those kinds of things.

Zollo: “But the enemy I see wears a cloak of decency…” [from “Slow Train”].

Dylan: Now don’t tell me… wait… Is that “When You Gonna Wake Up”?

Zollo: No, that’s from “Slow Train.”

Dylan: Oh, wow. Oh, yeah. Wow. There again. That’s a song that you could write a song to every line in the song. You could.

Zollo: Many of your songs are like that.

Dylan: Well, you know, that’s not good either. Not really. In the long run, it could have stood up better by maybe doing just that, maybe taking every line and making a song out of it. If somebody had the will power. But that line, there again, is an intellectual line. It’s a line, “Well, the enemy I see wears a cloak of decency,” that could be a lie. It just could be.

Whereas “standing under your yellow railroad,” that’s not a lie.

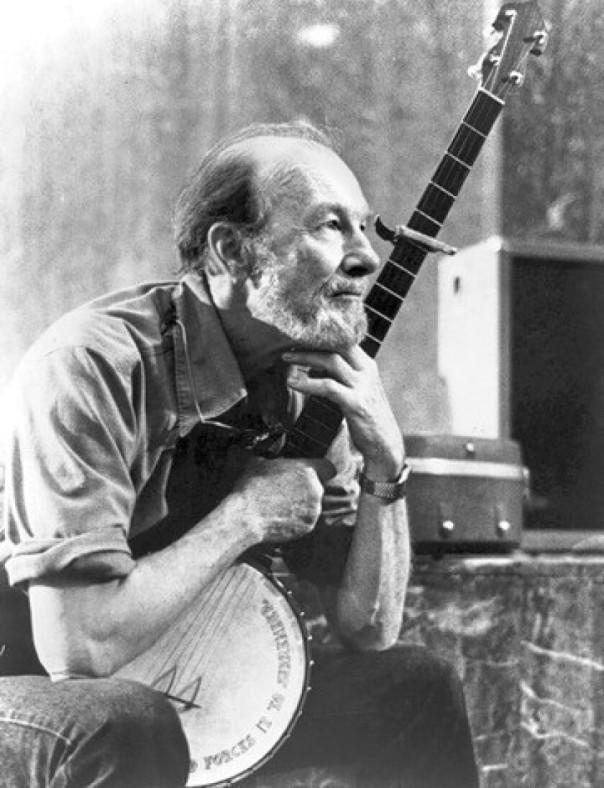

To Woody Guthrie, see, the airwaves were sacred. And when he’d hear something false, it was on airwaves that were sacred to him. His songs weren’t false. Now we know the airwaves aren’t sacred but to him they were. So that influenced a lot of people with me coming up. Like, “You know, all those songs on the Hit Parade are just a bunch of shit, anyway.”

It influenced me in the beginning when nobody had heard that. Nobody had heard that. You know, “If I give my heart to you, will you handle it with care?” Or “I’m getting sentimental over you.” Who gives a shit! It could be said in a grand way, and the performer could put the song across, but come on, that’s because he’s a great performer not because it’s a great song. Woody was also a performer and songwriter. So a lot of us got caught up in that.

There ain’t anything good on the radio. It doesn’t happen. Then, of course, the Beatles came along and kind of grabbed everybody by the throat. You were for them or against them. You were for them or you joined them, or whatever. Then everybody said, Oh, popular song ain’t so bad, and then everyone wanted to get on the radio. [Laughs] Before that it didn’t matter. My first records were never played on the radio. It was unheard of! Folk records weren’t played on the radio. You never heard them on the radio and nobody cared if they were on the radio. Going on into it further, after the Beatles came out and everybody from England, Rock and Roll still is an American thing. Folk music is not. Rock and roll is an American thing, it’s just all kind of twisted. But the English kind of threw it back, didn’t they? And they made everybody respect it once more.

So everybody wanted to get on the radio. Now nobody even knows what radio is anymore. Nobody likes it that you talk to. Nobody listens to it. But, then again, it’s bigger than it ever was. But nobody knows how to really respond to it. Nobody can shut it off. [Laughs] You know? And people really aren’t sure whether they want to be on the radio or whether they don’t want to be on the radio. They might want to sell a lot of records, but people always did that. But being a folk performer, having hits, it wasn’t important. Whatever that has to do with anything… [Laughs]

Zollo: Your songs, like Woody’s, always have defied being pop entertainment. In your songs, like his, we know a real person is talking, with lines like “You’ve got a lot of nerve to say you are my friend.”

Dylan: That’s another way of writing a song, of course. Just talking to somebody that ain’t there. That’s the best way. That’s the truest way. Then it just becomes a question of how heroic your speech is. To me, it’s something to strive after.

Zollo: Until you record a song, no matter how heroic it is, it doesn’t really exist. Do you ever feel that?

Dylan: No. If it’s there, it exists.

Zollo: You once said that you only write about what’s true, what’s been proven to you, that you write about dreams but not fantasies.

Dylan: My songs really aren’t dreams. They’re more of a responsive nature. Waking up from a dream is… when you write a dream, it’s something you try to recollect and you’re never quite sure if you’re getting it right or not.

Zollo: You said your songs are responsive. Does life have to be in turmoil for songs to come?

Dylan: Well, to me, when you need them, they appear. Your life doesn’t have to be in turmoil to write a song like that but you need to be outside of it. That’s why a lot of people, me myself included, write songs when one form or another of society has rejected you. So that you can truly write about it from the outside. Someone who’s never been out there can only imagine it as anything, really.

Zollo: Outside of life itself?

Dylan: No. Outside of the situation you find yourself in. There are different types of songs and they’re all called songs. But there are different types of songs just like there are different types of people, you know? There’s an infinite amount of different kinds, stemming from a common folk ballad verse to people who have classical training. And with classical training, of course, then you can just apply lyrics to classical training and get things going on in positions where you’ve never been in before. Modern twentieth century ears are the first ears to hear these kind of Broadway songs. There wasn’t anything like this. These are musical songs. These are done by people who know music first. And then lyrics. To me, Hank Williams is still the best songwriter.

Zollo: Hank? Better than Woody Guthrie?

Dylan: That’s a good question. Hank Williams never wrote “This Land Is Your Land.” But it’s not that shocking for me to think of Hank Williams singing “Pastures of Plenty” or Woody Guthrie singing “Cheatin’ Heart.” So in a lot of ways those two writers are similar. As writers. But you mustn’t forget that both of these people were performers, too. And that’s another thing which separates a person who just writes a song… People who don’t perform but who are so locked into other people who do that, they can sort of feel what that other person would like to say, in a song and be able to write those lyrics. Which is a different thing from a performer who needs a song to play on stage year after year.

Zollo: And you always wrote your songs for yourself to sing —

Dylan: My songs were written with me in mind. In those situations, several people might say, “Do you have a song laying around?” The best songs to me — my best songs — are songs which were written very quickly. Yeah, very, very quickly. Just about as much time as it takes to write it down is about as long as it takes to write it. Other than that, there have been a lot of ones that haven’t made it. They haven’t survived. They could . They need to be dragged out, you know, and looked at again, maybe.

Zollo: You said once that the saddest thing about songwriting is trying to reconnect with an idea you started before, and how hard that is to do.

Dylan: To me it can’t be done. To me, unless I have another writer around who might want to finish it… outside of writing with the Traveling Wilburys, my shared experience writing a song with other songwriters is not that great. Of course, unless you find the right person to write with as a partner… [Laughs] … you’re awfully lucky if you do, but if you don’t, it’s really more trouble than it’s worth, trying to write something with somebody.

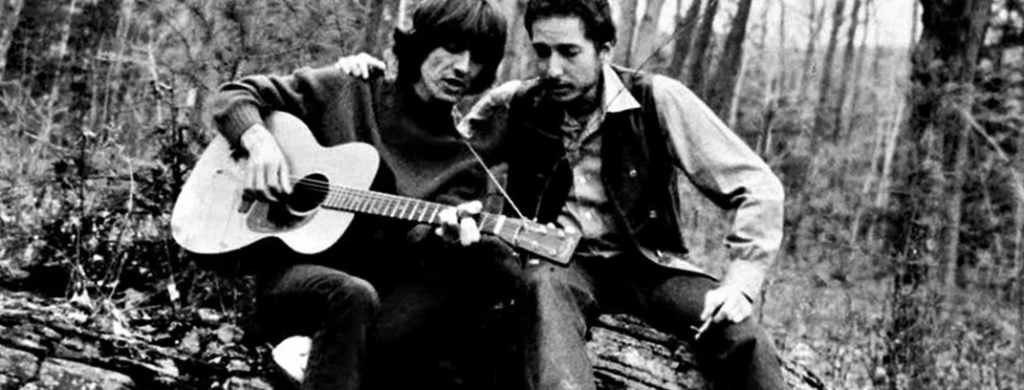

Zollo: Your collaborations with Jacques Levy came out pretty great.

Dylan: We both were pretty much lyricists. Yeah, very panoramic songs because, you know, after one of my lines, one of his lines would come out. Writing with Jacques wasn’t difficult. It was trying to just get it down. It just didn’t stop. Lyrically . Of course, my melodies are very simple anyway so they’re very easy to remember.

Zollo: With a song like “Isis” that the two of you wrote together, did you plot that story out prior to writing the verses?

Dylan: That was a story that [Laughs] meant something to him. Yeah. It just seemed to take on a life of its own, [Laughs] as another view of history. [Laughs] Which there are so many views that don’t get told. Oh history, anyway. That wasn’t one of them. Ancient history but history nonetheless.

Zollo: Was that a story you had in mind before the song was written?

Dylan: No. With this “Isis” thing, it was “Isis”… you know, the name sort of rang a bell but not in any kind of vigorous way. So therefore, it was name-that-tune time. It was anything. The name was familiar. Most people would think they knew it from somewhere. But it seemed like just about any way it wanted to go would have been okay, just as long as it didn’t get too close. [Laughs]

Zollo: Too close to what?

Dylan: [Laughs] Too close to me or him.

Zollo: People have an idea of your songs freely flowing out from you, but that song and many others of yours are so well-crafted; it has as ABAB rhyme scheme which is like something Byron would do, interlocking every line —

Dylan: Oh, yeah. Oh, yeah. Oh, sure. If you’ve heard a lot of free verse, if you’ve been raised on free verse, William Carlos Williams, e.e. cummings, those kind of people who wrote free verse, your ear is not going to be trained for things to sound that way. Of course, for me it’s no secret that all my stuff is rhythmically oriented that way. Like a Byron line would be something as simple as “What is it you buy so dear/with your pain and with your fear?” Now that’s a Byron line, but that could have been one of my lines. Up until a certain time, maybe in the twenties, that’s the way poetry was. It was that way. It was… simple and easy to remember. And always in rhythm. It had a rhythm whether the music was there or not.

Zollo: Is rhyming fun for you?

Dylan: Well, it can be, but, you know, it’s a game. You know, you sit around… you know, it’s more like it’s mentally… mentally… it gives you a thrill. It gives you a thrill to rhyme something you might think, “Well, that’s never been rhymed before.” But then again, people have taken rhyming now, it doesn’t have to be exact anymore. Nobody’s going to care if you rhyme ‘represent’ with ‘ferment,’ you know. Nobody’s gonna care.

Zollo: That was a result of a lot of people of your generation for whom the craft elements of songwriting didn’t seem to matter as much. But in your songs the craft is always there, along with the poetry and the energy —

Dylan: My sense of rhyme used to be more involved in my songwriting than it is… Still staying in the unconscious frame of mind, you can pull yourself out and throw up two rhymes first and work it back. You get the rhymes first and work it back and then see if you can make it make sense in another kind of way. You can still stay in the unconscious frame of mind to pull it off, which is the state of mind you have to be in anyway.

Zollo: So sometimes you will work backwards, like that?

Dylan: Oh, yeah. Yeah, a lot of times. That’s the only way you’re going to finish something. That’s not uncommon, though.

Zollo: Do you finish songs even when you feel that maybe they’re not keepers?

Dylan: Keepers or not keepers… you keep songs if you think they’re any good, and if you don’t… you can always give them to somebody else. If you’ve got songs that you’re not going to do and you just don’t like them… show them to other people, if you want. Then again, it all gets back to the motivation. Why you’re doing what you’re doing. That’s what it is. [Laughs] It’s confrontation with that… goddess of the self. God of the self or goddess of the self? Somebody told me that the goddess rules over the self. Gods don’t concern themselves with such earthly matters. Only goddesses… would stoop so low. Or bend down so low.

Zollo: You mentioned that when you were writing “Every Grain Of Sand” that you felt you were in an area where no one had ever been before —

Dylan: Yeah. In that area where Keats is. Yeah. That’s a good poem set to music.

Zollo: A beautiful melody.

Dylan: It’s a beautiful melody, too, isn’t it? It’s a folk derivative melody. It’s nothing you can put your finger on, but, you know, yeah, those melodies are great. There ain’t enough of them, really. Even a song like that, the simplicity of it can be… deceiving.

As far as… a song like that just may have been written in great turmoil, although you would never sense that. Written but not delivered. Some songs are better written in peace and quiet and delivered in turmoil. Others are best written in turmoil and delivered in a peaceful, quiet way. It’s a magical thing, popular song. Trying to press it down into everyday numbers doesn’t quite work. It’s not a puzzle. There aren’t pieces that fit. It doesn’t make a complete picture that’s ever been seen. But, you know, as they say, thank God for songwriters.

Zollo: Randy Newman said that he writes his songs by going to it every day, like a job —

Dylan: Tom Paxton told me the same thing. He goes back with me, way back. He told me the same thing. Everyday he gets up and he writes a song. Well, that’s great, you know, you write the song and then take your kids to school? Come home, have some lunch with the wife, you know, maybe go write another song. Then Tom said for recreation, to get himself loose, he rode his horse. And then pick up his child from school, and then go to bed with the wife. Now to me that sounds like the ideal way to write songs. To me, it couldn’t be any better than that.

Zollo: How do you do it?

Dylan: Well, my songs aren’t written on a schedule like that. In my mind it’s never really been seriously a profession… It’s been more confessional than professional. Then again, everybody’s in it for a different reason.

Zollo: Do you ever sit down with the intention of writing a song, or do you wait for songs to come to you?

Dylan: Either or. Both ways. It can come… some people are… It’s possible now for a songwriter to have a recording studio in his house and record a song and make a demo and do a thing. It’s like the roles have changed on all that stuff. Now for me, the environment to write the song is extremely important. The environment has to bring something out in me that wants to be brought out.

It’s a contemplative, reflective thing. Feelings really aren’t my thing. See, I don’t write lies. It’s a proven fact: Most people who say I love you don’t mean it. Doctors have proved that. So love generates a lot of songs. Probably more so than a lot. Now it’s not my intention to have love influence my songs. Any more than it influenced Chuck Berry’s songs or Woody Guthrie’s or Hank Williams’. Hank Williams, they’re not love songs. You’re degrading them songs calling them love songs. Those are songs from the Tree of Life. There’s no love on the Tree of Life. Love is on the Tree of Knowledge, the Tree of Good and Evil.

So we have a lot of songs in popular music about love . Who needs them? Not you, not me. You can use love in a lot of ways in which it will come back to hurt you. Love is a democratic principle. It’s a Greek thing. A college professor told me that if you read about Greece in the history books, you’ll know all about America. Nothing that happens will puzzle you ever again. You read the history of Ancient Greece and when the Romans came in, and nothing will ever bother you about America again. You’ll see what America is. Now, maybe, but there are a lot of other countries in the world besides America… [Laughs] Two. You can’t forget about them. [Laughter]

Zollo: Have you found there are better places in the world than others to write songs?

Dylan: It’s not necessary to take a trip to write a song. What a long, strange trip it’s been , however. But that part of it’s true, too. Environment is very important. People need peaceful, invigorating environments. Stimulating environments. In America there’s a lot of repression. A lot of people who are repressed . They’d like to get out of town, they just don’t know how to do it. And so, it holds back creativity. It’s like you go somewhere and you can’t help but feel it. Or people even tell it to you, you know? What got me into the whole thing in the beginning wasn’t songwriting. That’s not what got me into it.

When “Hound Dog” came across the radio, there was nothing in my mind that said, “Wow, what a great song, I wonder who wrote that?” It didn’t really concern me who wrote it. It didn’t matter who wrote it. It was just… it was just there. Same way with me now. You hear a good song. Now you think to yourself, maybe, “Who wrote it?” Why? Because the performer’s not as good as the song, maybe. The performer’s got to transcend that song. At least come up to it. A good performer can always make a bad song sound good. Record albums are filled with good performers singing filler stuff. Everybody can say they’ve done that. Whether you wrote it or whether somebody else wrote it, it doesn’t matter. What interested me was being a musician. The singer was important and so was the song. But being a musician was always first and foremost in the back of my mind. That’s why, while other people were learning… whatever they were learning. What were they learning way back then?

Zollo: “Ride, Sally, Ride”?

Dylan: Something like that. Or “Run, Rudolph, Run.” When the others were doing “Run, Rudolph, Run,” my interests were going more to Leadbelly kind of stuff, when he was playing a Stella 12-string guitar. Like, how does the guy do that? Where can one of these be found, a 12-string guitar? They didn’t have any in my town.

My intellect always felt that way. Of the music. Like Paul Whiteman. Paul Whiteman creates a mood. Bing Crosby’s early records. They created a mood, like that Cab Calloway, kind of spooky horn kind of stuff. Violins, when big bands had a sound to them, without the Broadway glitz. Once that Broadway trip got into it, it became all sparkly and Las Vegas, really. But it wasn’t always so. Music created an environment. It doesn’t happen anymore. Why? Maybe technology has just booted it out and there’s no need for it. Because we have a screen which supposedly is three-dimensional. Or comes across as three-dimensional. It would like you to believe it’s three-dimensional. Well, you know, like old movies and stuff like that that’s influenced so many of us who grew up on that stuff. [Picks up Peruvian flute] Like this old thing, here, it’s nothing, it’s some kind of, what is it?… Listen: [Plays a slow tune on the flute] Here, listen to this song. [Plays more] Okay. That’s a song. It don’t have any words. Why do songs need words? They don’t. Songs don’t need words. They don’t.

Zollo: Do you feel satisfied with your body of work?

Dylan: Most everything, yeah.

Zollo: Do you spend a lot of time writing songs?

Dylan: Well, did you hear that record that Columbia released last year, Down In The Groove ? Those songs, they came in pretty easy.

Zollo: I’d like to mention some of your songs, and see what response you have to them.

Dylan: Okay.

Zollo: “One More Cup Of Coffee” [from “Desire”]

Dylan: [Pause] Was that for a coffee commercial? No… It’s a gypsy song. That song was written during a gypsy festival in the south of France one summer. Somebody took me there to the gypsy high holy days which coincide with my own particular birthday. So somebody took me to a birthday party there once, and hanging out there for a week probably influenced the writing of that song. But the “valley below” probably came from someplace else. My feeling about the song was that the verses came from someplace else. It wasn’t about anything, so this “valley below” thing became the fixture to hang it on. But “valley below” could mean anything.

Zollo: “Precious Angel” [from “Slow Train Comin'”]

Dylan: Yeah. That’s another one, it could go on forever. There’s too many verses and there’s not enough. You know? When people ask me, “How come you don’t sing that song anymore?” It’s like it’s another one of those songs: it’s just too much and not enough. A lot of my songs strike me that way. That’s the natural thing about them to me. It’s too hard to wonder why about them. To me, they’re not worthy of wondering why about them. They’re songs . They’re not written in stone . They’re on plastic.

Zollo: To us, though, they are written in stone, because Bob Dylan wrote them. I’ve been amazed by the way you’ve changed some of your great songs —

Dylan: Right. Somebody told me that Tennyson often wanted to rewrite his poems when he saw them in print.

Zollo: “I and I” [from “Infidels”]

Dylan: [Pause] That was one of them Caribbean songs. One year a bunch of songs just came to me hanging around down in the islands, and that was one of them.

Zollo: “Joey” [from “Desire”]

Dylan: To me, that’s a great song. Yeah. And it never loses its appeal.

Zollo: And it has one of the greatest visual endings of any song.

Dylan: That’s a tremendous song. And you’d only know that singing it night after night. You know who got me singing that song? [Jerry] Garcia! Yeah. He got me singing that song again. He said that’s one of the best songs ever written. Coming from him , it was hard to know which way to take that. [Laughs] He got me singing that song again with them [The Grateful Dead].

It was amazing how it would, right from the get go, it had a life of its own, it just ran out of the gate and it just kept on getting better and better and better and better and it keeps on getting better. It’s in its infant stages, as a performance thing. Of course, it’s a long song. But, to me, not to blow my own horn, but to me the song is like a Homer ballad. Much more so than “A Hard Rain,” which is a long song, too. But, to me, “Joey” has a Homeric quality to it that you don’t hear everyday. Especially in popular music.

Zollo: “Ring Them Bells” [from “Oh Mercy”]

Dylan: It stands up when you hear it played by me. But if another performer did it, you might find that it probably wouldn’t have as much to do with bells as what the title proclaims. Somebody once came and sang it in my dressing room. To me. [Laughs] To try to influence me to sing it that night. [Laughter] It could have gone either way, you know. Elliot Mintz: Which way did it go?

Dylan: It went right out the door. [Laughter] It went out the door and didn’t come back. Listening to this song that was on my record, sung by someone who wanted me to sing it… There was no way he was going to get me to sing it like that. A great performer, too.

Zollo: “Idiot Wind” [from “Blood On The Tracks”]

Dylan: “Idiot Wind.” Yeah, you know, obviously, if you’ve heard both versions you realize, of course, that there could be a myriad of verses for the thing. It doesn’t stop . It wouldn’t stop. Where do you end? You could still be writing it, really. It’s something that could be a work continually in progress.

Although, on saying that, let me say that my lyrics, to my way of thinking, are better for my songs than anybody else’s. People have felt about my songs sometimes the same way as me. And they say to me, your songs are so opaque that, people tell me, they have feelings they’d like to express within the same framework. My response, always, is go ahead, do it, if you feel like it.

But it never comes off. They’re not as good as my lyrics. There’s just something about my lyrics that just have a gallantry to them. And that might be all they have going for them. [Laughs] However, it’s no small thing.