In Memory of My Father

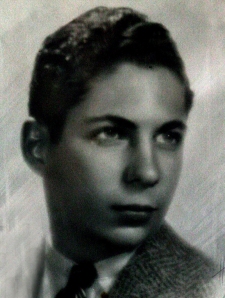

Burt Zollo

March 7, 1924 – April 25, 2014.

By PAUL ZOLLO

We called him the “Old Guy” since long before he was an old guy. He didn’t mind, it was funny. More than anyone I have ever known, he loved to laugh at himself.

Those of us who knew him were lucky – he was a gentle man, humble, sweet, loving, funny, extremely intelligent, and happy.

I wore one of his ties to his memorial, as did my son Joshua and my nephew James Zollo. I inherited all of his ties, and he had many beautiful ones. He hated wearing ties. He hated having to dress up. He hated pretense of any kind. And he would not want anyone to get maudlin or write overlong, impassioned tributes to him. Sorry Dad. Just this one more time.

Theodore Roethke, the poet, wrote “The right thing happens to the happy man.” My dad was a happy man. He truly was. He knew what made him happy – and he built his life around those things. Of course, family made him happy: his own parents, his three kids, his wife: in love with my mom for 64 years! And his grandchildren. Seven of them, each exceptional, special people. He loved each one.

In addition to family, the things that made my father happy were work – especially writing – travel, good food (especially my mom’s cooking), good wine, books, temple, tennis, art, music, laughter.

The good life.

Born in Chicago in 1924, he was an only child. He loved his parents with genuine heart and great devotion. Even now I come across evidence of this close, special love. Inscribed to his parents in the first book he wrote and published, is this:

“To the best parents – ever – Love, Burt.”

His father, Raymond Zollo – aka Poppa Ray – came to America in 1918 with his four brothers and sisters after their father, Barney Zlotnik, came here first from Gombin, Poland.

On Ellis Island, with the Statue of Liberty standing close by in the harbor, Zlotnik somehow became Zollo, which is an Italian name. We were never sure exactly why we got Zollo from Zlotnik (which translated, is Goldsmith). Poppa Ray used to say it was just a mistake, though his sister, our Aunt Harriet, once said, no, it was intentional. We didn’t want people to know the truth.

To this day I laugh over the fact that my mother would always scrutinize the names of any girlfriends I had, to determine if they were Jewish. (One, whose last name was Tang, inspired her to say, “She no lookee Jewish!”) And yet our own name betrayed our roots. I still joke (and in my dad’s tradition, few things matter more than levity, and a good joke is like currency that can be used forever) that we are indeed Italian, from the eastern end of Italy – Poland.

Poppa Ray was never far from that big boat that brought him, along with his family, into Ellis Island. He once told me, lest I thought he traveled in luxury, that they were “underneath, in steerage.” He remembered growing up wealthy in Poland, his grandfather showing them his life savings in a drawer filled with silver and gold coins. That is, until the Tzar took it all, leaving them and their fellow Jews impoverished.

On the boat my grandfather tasted ice-cream for the first time in his life. Vanilla. “It was so delicious that I ate so much, I got sick,” he told me once, as I drove him, as I did countless times along Sheridan Road, back to his home in the city. He preferred this route to the expressway, and he preferred my driving to my dad’s, who, he said, “drives too fast!”

Poppa Ray was a great role model in how a father loves a son – with a full heart. He worked for Groshire Clothes in the Merchandise Mart, and sold beautiful suits – and was always impeccably attired, of course. When he would come to our house for a barbecue out on the patio, he would be in a suit and tie. My dad would say, “Dad, you don’t have to wear a tie!” And he would say, “Burt, you know I am not comfortable otherwise.” He’d get my father a new set of suits twice a year, every year. Beautiful suits and shirts and ties.

Poppa Ray was devoted to his wife, my grandmother, Ester Zollo. She was a Lithuanian Jew, or Letvak, which also stood for “smart Jew,” and Poppa Ray always considered her smarter, and the source of my father’s prodigious intelligence. Like my dad, she had Parkinson’s, and had a strong tremor. Either the disease or her medication made her what we called senile back then. Often when we would be in public, she’d start singing. Loudly. Always old songs, like “Second Hand Rose.” So as never to leave her hanging in public, my father would sing along. And so would I.

When she was young, she was a flapper, a woman who loved to drink, gamble and dance. Like my father, she was very funny, and unlike him, was an ace gin-rummy player who never lost. She even had jokes for all the cards. As she would put down a three, she’d say, “A three. And those don’t grow in Brooklyn.”

Both Ester and Ray were devoted to their son, who they named, for a reason I never knew, Burton Murray Zollo. My dad told me when he was a kid, like me, he couldn’t say his Rs. So when asked what his name was, his pronunciation of Burton sounded like “Button.” All the kids taunted him by calling him Button. Which he didn’t like, but even decades later, rather then be weepy about it, he’d laugh. He always could see the humor in things. For the rest of his life my mother called him Button. (He called her Lotie-Doll.)

When he went to college, he lived at home with his folks in their one-bedroom apartment on the 16th floor at 3520 Lake Shore Drive, just blocks from the temple. They insisted that my dad sleep in the bedroom, and they slept on the couch. I remember when my father told me this, in their apartment many decades after he went to college. He told me and I was disbelieving. You slept in the bedroom and they slept on the couch? He nodded, and that was all I needed – a tacit understanding that, yes, that’s what love means.

He went to Senn High School. He had his mind set on attending Northwestern, but was initially rejected. His mom knew it was because he was a Jew, and they had filled their quota already. She didn’t like that. Like my dad, she had a strong reaction against any perceived injustice. After all, my dad had perfect grades – all As – and perfect attendance. She went there, insisted they explain, and I am not sure what else transpired, but Burt Zollo was accepted at Northwestern. Even though.

He graduated with honors. He did have the unfortunate luck, though, to turn 18 right in the middle of WWII, 1942, after his freshman year.

He volunteered for the Air Force, but was rejected because of his bad eye-sight, something which bothered him his whole life.

So in November, 1942, he enlisted, reluctantly, into the army. He started service in April of 1943. Three years he served, until March, 1946, when he was awarded with three medals: the Good Conduct Medal, the European African Middle Eastern Theater Service Medal and the American Theater Service Medal.

I also still have his dog-tags, also, which have his parent’s Chicago address on them. Which I love, because it’s my father and his father together forever.

But before this seems too patriotic and pro-military, it should be pointed out that my dad hated the army. He hated the war. It was the loneliest, saddest part of his life. He kept a journal during the war, and it’s a journal of much sorrow. It was the only chapter of his life that wasn’t a happy one.

He became a sergeant in the army. A typist and a supply clerk at first, he used to joke that he was awarded with a Purple Heart because he attacked by a German. Unfortunately, it was a German Shepherd. And an American one, who did bite down hard on his hand and refuse to let go.

He became a prison guard of German prisoners in Le Mans, France, where he would take envoys out for needed supplies, always intentionally taking a few extra days so as to enjoy the French countryside, its good food, wine and French girls. He’d take a few of the German prisoners along as crew, and told me they would never try to escape as the French farmers, upon finding them, would “kill them with their pitchforks.”

He would then return a triumphant hero with trucks of cigars and whiskey. As always, he figured out a great system that nobody else conceived, and it benefited everyone. It’s a story he turned into his first published novel, Prisoners.

He hated Germans, and Germany, for the rest of his life. When I was planning a college trip around Europe, he insisted I get through all of Germany quickly, to enjoy the parts of Europe that mattered, like France. (He loved France always – the language, which he learned to speak, the food, the women, the beauty).

He was a creative prison guard, and encouraged his inmates to do art. Since there was a surplus of old brass mortar shells, he arranged for them to have the tools to turn these into ash-trays. Beautiful ones, inscribed, with working lighters installed into their cores. He brought home one of these for his parents, a gleaming mortar shell ash-tray which I viewed every week through my childhood Sundays, as it became the centerpiece of their home, and Poppa Ray smoked ample cigars. It was shiny brass, inscribed with the message: To Mom and Dad Love from Burt * France, 1945.

When Poppa Ray died, I asked for this ash tray. I was in Chicago, and helped my father clean out Poppa Ray’s apartment. It was a sad day – the saddest – and as we had to decide what to keep and what to throw away, my father cried. I tried to make jokes but it didn’t help. Losing a dad isn’t easy, as I sadly now understand.

Traveling back to California, I put the ash-tray – a big heavy hunk of brass – in my backpack, which I checked through security. How I remember the wide-eyed dramatic disbelief of the guy who viewed the x-ray, vehemently pointing at the screen and inviting all his colleagues to gather round and look. Today I scoff at my stupidity, not realizing a metal bomb in a backpack might garner some worry.

“It’s okay!” I said. “It’s an ash-tray!”

“An ash-tray made out of a mortar shell?!”

“Yes!”

They took it out, I explained its historic origins, and every security official took their time examining it, all with smiles. My dad loved that story.

He was a secret poet. He wrote poems, but rarely let anyone read them. Which says so much about the man. The poetry was there always, in his heart, but there was no need to parade that. But when I cleaned out all his files, I found several beautiful poems, including this one, a short poem he wrote about being one of those guys from the “greatest generation,” who went off to fight, and came back to talk about it for the rest of their lives.

The poem’s about the war, and the stories – but true to my father’s empathetic spirit – it’s also about how other people are bored of these stories.

War Stories

I heard my wife, in the back of the car, say smugly

They love to tell war stories, they never tire of them, she’s right

Their endless resurrection of those years

Their war, one of so many for a land so young.

Driving a car made by the enemy we vanquished in World War II

I strive for the reality of those years of my youth, my combat

Embellishing the recollections, trying to capture its reality,

Recognizing my remarks may seem dull to him, my friend, I say

You were in the Pacific, weren’t you, as far as China.

We listen to each other’s claims, a time-locked fragment

Now momentous, a stone.

One of the happiest days of his life, he told me, was when he came back to America in 1946. His dad met him at the harbor in New York City, where his boat came in (and not far from where my grandfather’s boat came in just decades earlier), along with his brother, our Uncle Julius. Like good Jews they went directly to the place most appropriate to celebrate this homecoming for this reluctant but conquering warrior – the Carnegie Deli – where they celebrated the way he always liked to most – with an enormous pastrami sandwich, several beers, and matzo ball soup.

The good life.

Back in Chicago he returned to Northwestern, where he graduated with honors from the Medill School of Journalism.

He met my mom on a blind date in 1950 set up by Skip Grossman. She was very beautiful, quite reminiscent of a young Audrey Hepburn, and came from a very good family.

Her father, my other grandpa, was A.J. Clonick, a steel magnate who owned Clonick Steel in Chicago (their office in the landmark Monadnock Building, the first all-steel building in Chicago), and was also instrumental in securing the funds to build their temple, completed in 1928, Temple Sholom, at 3580 N. Lake Shore Drive, where it still stands. When it was constructed, there was no outer drive yet in the city, so it was known as “The Temple on the Lake.”

Poppa Clonick owned a beautiful four-story apartment building, where he raised his family, at 451 Aldine, in Chicago, just blocks from the temple. When my folks were married, they moved into an apartment just a few doors down. My mom’s sister, Shirley, lived with her family in the top floor apartment of this building. I spent endless hours of my childhood in these two apartments, which were vast.

I’ll always remember that the maintenance man of the building, who lived in an apartment on the ground floor, wrote children’s books such as Up From Appalachia under the name Charles Raymond, a pursuit he could pursue thanks to the generosity of my grandfather, who never raised his rent – through decades – since the day he and his wife moved in.

My dad loved and respected Poppa Clonick. But to me, he never praised him for his wealth or business success. He praised him for his wisdom and his generosity. In Poppa Clonick’s family room were floor to ceiling bookshelves, filled with great books that he had read, the “sign of a learned man,” as my dad would say.

My parents were married that year, on June 8, 1950. The wedding was in the Clonick home. My dad used to joke always, “It was a very nice wedding, I was glad there was room in the kitchen for my parents.”

Professionally he worked first at Coronet Magazine, then at Esquire. He was considered a double threat at both magazines. Though he only really wanted to write – to be a journalist – his savvy led him to discover what became known as PR, or Public Relations, the art and science of publicity and promotion, the way an article in a magazine about a hotel, or restaurant, or celebrity can be used to promote that entity. Now PR is woven into the fabric of our culture. But he was truly one of the first to define the field.

When Esquire moved to New York, my father yearned to go as well. Though he always loved his hometown of Chicago, he never hid his great love of New York City, which he considered one of the greatest and most exciting places in the world. So I asked him, decades later, why he didn’t go. “It wasn’t an option,” he said. “Our family is here.”

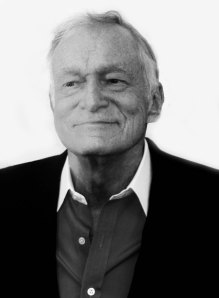

His best pal at Esquire was a young man named Hugh Hefner. Hef was, my dad told me, a funny guy. Creative, idiosyncratic, a smart Jewish Chicagoan. My dad gave him his first pipe, which became part of his image. Like my dad, he elected to stay in Chicago, near his family.

Together, they decided to create their own magazine, and their first was one devoted to Chicago itself, called CHI. They put together a business plan, which I still have, and got two investors – Poppa Ray and Poppa Clonick. But Hef soon became more interested in his new project, a magazine that would publish the writing of the finest writers in the world – like The New Yorker – but with girly photos. He called it Playboy, and invited my dad to be a partner.

My father said no. He didn’t think it was a good idea! He said to me, decades later, “Great literature and girly photos? I didn’t think it would work!”

He did write for the first many issues, including the famous inaugural issue featuring Marilyn Monroe on the cover, and inside. Hef paid him in Playboy stock.

For this famous first issue he wrote an article called “Miss Gold-Digger of 1953.” It was a treatise on how not to allow a woman trap you into marriage. Of course, my father, and Hef, were both already married at this point. During our childhood, he remained almost embarrassed by his Playboy-connections, and never did we see this issue, or his story.

But Mother Jones magazine came out with a piece in 1983 about it. Although my dad used a pseudonym (Bob Norman – even Hef didn’t put his name in the first issue, as this was very racy stuff in 1953), his identity was divulged in various Playboy anniversary issues over the years. Mother Jones wrote about my dad, and about the profound impact of this one piece.

When I asked him about writing this story, he initially said he didn’t remember writing it, which I didn’t doubt. But, he said, “if I did, it wasn’t my idea, it was Hefner’s. I was just fulfilling an assignment.” But he did it well. It was one of the first and most eloquent definitions of the “Playboy male.”

We joked about his bad call for decades, turning down Hef instead of becoming a partner in his new empire. We joked about the fact that my brother and I could have taken over Playboy in the 80s, as did Hef’s daughter, and could be sitting in the grotto right now with Playboy bunnies. My dad loved to laugh about it. “I thought it was a terrible idea!” he’d say with his big generous smile, inviting one and all to laugh at him.

But the truth is my dad was not a Playboy. He would not have been happy in that world. Hef would have parties that started at 11 pm. Not my dad’s thing. Or my mom’s. And Playboy was Hefner’s vision, not my dad’s, and so though he joked about missing out, I know he knew it was for the best.

He was much happier in the life he created. A house in the suburbs with a happy family of five. There were three of us kids. a daughter, a son, and me, the baby. In the momentous year of 1960, we moved to a house, his first. To Wilmette, which at the time was known as “No Man’s Land,” so far from the city was it then considered. Ever since he was a kid growing up in the city, he dreamed of a backyard – a garden – a house. And that is what he created. On Sandy Lane, a new part of west Wilmette built on former fields of corn.

When we moved in, there was still a farm-house and a chicken coop (when the coop was demolished and a new artery of Sandy Lane was built into what was once wild, my best friend Andy Kurtzman moved into a house, with his family, on that spot.) When the last daughter of the farmer died, the little farm house near our home was bulldozed, and her farm was transformed into Centennial Park. Our house was the only one on the street with Clonick steel beams. If ever’s there’s an earthquake in Illinois, it will be the last house standing.

Instead of starting a magazine, he became a public relations man, defining the field, as mentioned, when he entered it, even writing the very first textbook on the subject The Dollars And Sense of Public Relations, McGraw Hill, 1967. I can remember like yesterday when it was published. My mom planned a surprise party for him that night. Our house was full of people, and he came home late that night – about 7:30. We heard the garage door open, and we knew he was home. We were quiet and he walked through the garage door, tie undone, sleepy eyes – and we all screamed “Surprise !!”

He darted back into the garage to redo his tie. And then joined the party.

Being an author was a dream come true for him. He enjoyed PR, he loved his office in the city and he loved Chicago. But he always yearned to do something more artistic. He wanted to write books.

I remember going with him to the Wilmette Public Library, back before the world went digital, when they still had those long wooden card catalogues. How I would delight in finding his name in there. And we would joke: you know who else is in there with you? Shakespeare! Mark Twain! Dickens!

And the guy he loved the most: Hemingway. Not bad company.

When he wrote for Playboy, Hef paid him in stock, worthless at the time, but ultimately worth a small fortune when it went public in the early 70s. My dad sold all his stock, which made him a millionaire overnight. Irv Kupcinet, a friend of my father’s who wrote the daily Kup’s Column in the Chicago Sun-Times, wrote of my father’s great fortune. I was in 7th grade then, and wanted to take it to school to show everyone. He said no. This is a blessing, he said, but one we will keep to ourselves. He was embarrassed by it.

Hefner wasn’t happy that my dad sold all of his stock, and it forever hurt their relationship. I asked my dad, just a few years ago, why he did it. He admitted that he didn’t really understand the implications at all of selling it all, but was simply following the advice of my cousin Michael, who was his lawyer. Though he was private about his wealth, he used it to give him more of the good life for which he always yearned. Had we not strongly objected, he would have been happy to move to a bigger house.

Instead he bought beautiful modern art for that home, and a sports car. One of many. And he was able to then move towards his real dream – of writing full time. So he retired gradually – cutting down his days at the office until he left to become a full-time writer. To write books Novels. Non-fiction was great, but for him it was all about fiction. Like the work of the people he loved best: Saul Bellow, John Updike, Phillip Roth. And, of course, Hemingway.

As soon as my father began retiring, my mom went to work. Recognizing, evidently, that daily separation was necessary for their marriage, she pursued her great talent as a needlepointer by getting a job at a neighborhood needlepoint store called The Hooker’s Nook. My dad delighted in telling anyone who would listen, “My wife’s a hooker!”

His office at home was paradise. Soft-lighting, always smelling of pipe tobacco – a friendly smell I liked – filled with great books and hip art. And that old Royal acoustic typewriter right in the center. WFMT would be tuned into classical or a Mozart album would be on. He’d get so engrossed in his writing that I was not allowed to just walk in. I had to announce myself from a distance as I approached: HERE I COME, HERE I COME!!!! Otherwise, he would jump out of his skin, exactly as I am to this day when my son walks into my office, unannounced.

He had a lot of ideas for novels, and started many. But getting a first novel published, as many of us know well, is not easy. He got rejected many times. And he did get discouraged. But never derailed. Never did he even entertain the thought of giving up.

Truth is his first novels weren’t his best work. They were imitative more than personal. He didn’t trust that he could write about his own thoughts, his own spirit, his own life.

But one night when I was visiting from California with my wife, he started telling us stories about his time in the war. About the envoys, the French countryside, the returning hero. We told him, “Write that book! That is a unique story.”

At first he wasn’t sure. “But there are already so many books about the war, who wants another?”

We assured him his story was unique – and historic – and great. And nobody could write it except him. So he agreed.

I can’t recall how long it took him to write, but I don’t think it was much more than one year. He was dedicated. He loved to write, and would do it – happily – every day. He was passionate and he was diligent.

Then triumph. Chicago Academy Press accepted it for publication. And in 2003, when my dad was 79 years old, it was published. Prisoners. A dream come true. He was a novelist now and forever.

The book focused on its protagonist, Sandy Delman, a Jewish kid from Chicago. Much of it was true, though Delman was tall, a former football player, who would tower over others on the tennis court. Tower? We never towered over anyone ever. But, as my nephew Jason Miller rightly pointed out, this was fiction.

The book got good reviews. Kirkus called it “delightfully old fashioned” – and “a great debut.” I’d say any debut at 79 is great.

And he taught me the lesson he taught me over and over. Never give up on your dreams. Anything is possible. Never stop.

We had a book-signing party for him at my brother Peter’s beautiful home, and few things were ever as happy or sweet as seeing the pride in his smile as he signed everyone’s books, and the knowledge that some dreams – if you never let go of them – can come true.

One day he called me up and said the publisher of Prisoners wanted to change the name. And my dad didn’t like the change.

He said, “He wants to call it The Jewish God.” The Jewish God? Why would he do that? Didn’t make sense. So I called him. Jordan Miller is his name, and he’s from Boston. And speaks like a Bostonian.

“No, not Jewish God,” he said. “Jewish Guard.” In his thick Boston accent, it sounded like God. My dad thought that was wonderfully funny when I explained. We agreed, and that became the sub-title for the paperback edition.

His next novel was about his time doing PR in Chicago in the early 60s. It was originally called P.R. but he changed that to State & Wacker, a better title. When we couldn’t find a publisher, I convinced him that we could publish it ourselves. I edited it, and with iUniverse we published State & Wacker in 2009. It was about the swinging Sixties long before Man Men covered the same territory.

He was my arbiter of what mattered – what books, what movies, what art. He taught me the beauty of abstract art, a modern concept for one his age to grasp. He was a modern man. He taught me about food (French is the best in the world, he insisted always), movies (he knew all the films and all the stars from his youth, so that during my tour of old Hollywood he was one of the most enthused ever: “Beulah Bondi lived there?” He’d then proceed to school me about Beaulah, and other stars I knew by name only.)

More than anything, he taught me about literature. He had all the great books on his shelves: Steinbeck, Fitzgerald, Chekhov, Dostoevsky, Kafka, etc. He read them all. When I moved to Hollywood he gave me one of the best gifts ever: a first edition of Day of the Locust by Nathanael West, the “best book on Hollywood,” in his estimation. It was the first book from his collection that became mine. I now have several bookshelves of his beloved books.

He accepted some aspects of modern times – abstract art, free verse poetry – with a modern heart, whereas other aspects were challenging. Amazingly, he did make the transition – however challenging – from typewriter to computer (though he never learned the terms – “Desktop? Why does everyone ask about my desktop?”)

But when the FAX machine came into vogue, he told me he thought it was foolish. “What’s the big rush?” he asked. In other words – why does the world need things so fast? Things were just then starting to speed up, and he always preferred slowing down, with a good book or the new issue of The New Yorker. He belonged to an earlier age.

He always wanted to move when we were kids, even before he had the wealth to make such a move easy. Peter and I would find real estate photos and flyers in his brief-case, and steal them, figuring that would keep us in our home. Our house was a tract home in Wilmette, which was heaven for him when he first moved in, 1960, but which seemed conventional to him by 1970. He loved modern art, and he wanted a home as unique and modern as a Picasso.

When all us kids had moved out (I was the last to leave, in 1976), he started seriously searching for a new home. My mom was not an easy customer in this regard. She agreed to move only on the condition that he found a house in the same suburb, Wilmette (so she could go to the same supermarket, primarily), and it had to be a one-story house, as she knew they weren’t getting younger, and didn’t need any stairs into their dotage.

And so he embarked on what I called, in a parody song at the time I wrote for a party, “the impossible dream.” To find a house that fit those narrow criteria.

But he had a way of realizing his dreams. But it took years! Many times I visited houses with him. But never did we find one that was right, and that would suit my mom. And keeping his beloved wife happy, more than just about anything, was his priority.

But he did it. He found the house. At 1000 Locust Rd. in Wilmette. In what was a much tonier section of Wilmette than we lived in, what is known as Indian Hills, a beautiful neighborhood of mostly stately mansions on large and beautiful lots. But the house they found was an exception, and truly exceptional. It was modern – one story – on a beautiful lot with winding driveway, and a gorgeous terraced backyard. It was a house so beautiful even my own mother couldn’t say no.

In 1989, they moved in. And they made it their own. With no kids, they could decorate it exactly the way they both loved the most – which was white and pristine. White carpets, white couches, and the walls filled with beautifully chromatic abstract-expressionist canvasses. There were also assorted sculptures, and some furniture that were really art-pieces. It was stunning. To this day, I have rarely been in a house more beautiful. And I’ve been in some amazing homes.

He was happy there. He loved his home. When we had to move them out to assisted living just a few years ago, we put it on the market and were told it was a “knock-down.” The land around it was large and beautiful, and someone would want to build a big house there. Our realtor was right. That house now belongs, like my dad and Lincoln, to the ages.

There were three times I remember him crying. Well, not a real cry – but tearing up. The first was when RFK was shot, the last was when we cleaned out his childhood home after Poppa Zollo’s death, sorting through his father’s belongings.

The third time was when my brother Peter went away to college. He went to Drake, in Des Moines, Iowa, only about a five-hour car ride. So the three of us went on this journey – Dad, Peter and me. All I remember is after Peter was gone, and it was just the two of us in the car, he cried. We both knew an era was over forever.

But he was quick to find joy in the next chapter. I can remember vividly the day Peggy’s first child was born, Jason Miller, in 1978. My father was as ecstatic as a new father himself. With my mom he transformed Peter’s old room into a nursery, so they could be active grandparents. Today Jason works in the Obama administration, a career that gave my dad great pride.

But he loved and was proud of every grandchild, whether it would be Ben Zollo, who became a great educator, or Liza Miller, a wonderful singer and actress. He delighted in each of them.

I remember the day I learned that the child my wife and I were expecting was a boy. On my piano I had the photos of my father and his father, and I teared up at the understanding that now, through me, a new Zollo son would be born. I was, and am, proud of this heritage of love.

He loved Chicago. He delighted in its great architecture, its famous buildings and museums, its great restaurants, and its resplendent lay-out along the lake and river. As much as he loved Manhattan, he often said, “There is no more beautiful American city.” Michigan Avenue, he told me, was more beautiful than any other urban American thoroughfare.

When his own kids were born, so nervous was he, according to family legend, that he showered several times a day. That was the extent of his self-medication, a series of showers. He did love wine, as mentioned, and he would drink a Tanqueray martini, dry on the rocks with lemon and olive – but usually only once a week, on Fridays, after work. My mom would prepare it, and it was usually my job to carry it upstairs to him, where he was changing out of business clothes with Huntley-Brinkley on. I would always sip it on the way upstairs, from as early as I can recall.

He loved going to baseball games – always at Wrigley Field – but his joy, as I recall, was most connected to the hot dogs and cold beer. He would let me sip the foam off his beer, and I remember, sitting in that hot Chicago summer sun, nothing tasted better ever than that beer. Lucky after this upbringing I didn’t become an alcoholic.

He delighted in my delight. As a kid, there was no greater day than that start-of-Spring moment when the ice had melted enough that, once again to my heart’s content, I could ride my bike. He’d give me permission – the streets wet still with melted ice and snow up on the curbs – and I would fly out of our garage on my bright red Schwinn. And he would stand there beaming, sharing in my joy, loving how fast I could zip away and how quickly I’d always return.

He loved tennis. Watching and playing. He’d play twice a week, almost every week, and was proud that at least one of his sons, Peter, became a truly great tennis player.

I remember going with him to one of many outdoor courts near our home, and play on my own as he’d play with his tennis nemesis, his good pal and next-door neighbor, Dr. John Phillip. John was a much better player than my dad, and always won. And though this was tough on my dad, being the perpetual loser, it gave him something to strive for, a goal. To simply beat John. Even once.

He didn’t mind having a competitor who was a superior player, as he knew it pushed him to play better. One day he came home, beaming, and announced, “I won!”

“What?” we all asked in unison, “You beat Dr. Phillip?”

“Yep!”

“What happened? Did he break his leg?”

“Nope. His ankle. They say it’s just a sprain. But that still counts as a win!”

In later years, when I was the only kid left at home, as my brother and sister had already gone on to college and marriage, he would often play tennis on Thursday nights. Being him, he turned this routine into a treat for all of us. On the way home, he would always stop at Peacock’s Dairy Bar to pick up ice-cream treats for himself, my mom and me. My standing order was a hot fudge sundae with mocha chip ice-cream. Not once did he forget, or get it wrong. That’s who he was.

He loved playing chess. He got a nice Spanish chess-board on a trip to Madrid, and a book of rules. He never was a very good player, though, as his grandkids also remember. He’d never really remember all the rules – like the strange privileges the knights had – and was always going to the book to check. But as with tennis, it wasn’t winning that mattered to him the most. It was the joy of the game, and the partnership it created.

He was political. Always liberal, except for one unfortunate season in the 80s when for some reason he loved Reagan. He did PR for Adlai Stevenson’s failed presidential bid, and always told me he’d have been a much better president than Eisenhower.

In 1968 he was for Eugene McCarthy first, and then Humphrey, who lost to Nixon. When Nixon was reelected in ’72, he encouraged me to wear a black armband to school.

When I was invited to participate in a debate in 5th grade on Capital Punishment, he explained to me his vehement and logical opposition to the death penalty, and equipped me with all the best arguments that might come up. I so whipped my competition – so prepped and ready I was, and almost reverent with this awakening consciousness – that the teacher was astounded.

“They’re gonna bring up ‘an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth,'” he said. “They always do. Hit back with “the bible also teaches us to “Turn the other cheek.'” Sure, it wasn’t our testament that taught that, but he knew his stuff, and it worked.

He met Harry Truman in 1961 when the former president had written his autobiography, Mr. Citizen. He asked Truman to sign the book to his kids, which he did: “To Peggy, Peter and Paul Zollo, from Harry Truman, 1961.”

Truman then asked my dad if he had voted for him. When my dad said yes, Truman added, “Kindest regards.”

He always wanted a big dog, his whole life. A dalmatian, maybe, or a collie. My mom held off on any dog until 1967, at which point somehow her resistance was worn down, and she gave in. But only if it was a small dog. A miniature schnauzer, like Skipper, the beloved dog of Aunt Shirley and Uncle Miles.

So we got Nappy. Which was short for Napoleon Zollo, a play on Napoleon Solo, of Man from UNCLE fame. Nappy was small but feisty, and my dad loved him, of course. We all did. He was one of us. Small but spirited.

My cousin Nancy made the best Nappy joke ever. “Napoleon,” she said once, “don’t pull your bone apart.” In 1967, it didn’t get better.

He loved music. He loved folk music a lot – and had all the albums by Pete Seeger, Woody Guthrie, Leadbelly, The Weavers – all of it – before Peter or Peggy or I fell in love with that music. He idolized Pete, and taught me early on just what he mattered so much. It was the music, yes, but also the activism, the devotion to the good cause.

When Pete died this year, although he was 93, it was heartbreaking for us. As Peggy said, it was like losing a member of the family. One of my earliest memories was seeing a concert by Pete at a small club in the city, hosted by Studs Terkel, who my dad also knew and loved. That Pete and he would go out the same year seems so right.

(As music for his memorial, rather that somber classical music, my first idea, Peggy suggested Pete, and I knew that would be perfect. My nephew Ben Zollo put together a disc of Pete’s greatest hits, solo and with the Weavers, which we played as people came in.)

He also loved the music of his courtship with my mom: Sinatra, Judy Garland. Some Broadway musicals. He had all the early Judy Garland and Sinatra albums, and considered Sinatra one of the greatest vocalists of all time. He introduced me to In the Wee Small Hours, which schooled me on the greatness of Frank.

But his greatest passion was for classical music. As a kid, he studied piano seriously and even considered becoming a pianist. But when he learned that classical musicians practice up to eight hours a day, he was quickly dissuaded him from that dream. But his entire life he played the piano.

Late in life he went back to trying to play new pieces, and work on his technique. Mostly, though, he played three pieces, which we used to joke about. Just three. But all good!

They were “Pomp & Circumstance,” the famous graduation theme by Elgar (which often came in handy, as when we had a mock-graduations for Nappy), “Fur Elise” by Beethoven, the old stand-by we all learned, and “Claire de Lune” by Debussy, with its rich, soft modern harmonies, which will always remind me of my dad’s gentle, but modern, spirit.

He adored the Chicago Symphony. He had season tickets for their Friday afternoon shows and would take the bus from the suburbs “with the old ladies,” as he would laugh. And like being in Chicago during the Michael Jordan golden era of the Bulls, he was at the symphony during their golden era with Georg Solti as conductor. I remember him on the phone after, almost breathless, saying, “I cannot imagine there being a better symphony, or a better conductor, anywhere in the world.” He also loved when Daniel Barenboim took over.

During the Solti and Barenboim era, the concert master was Samuel Magid, whose grandson, Jared Rabin, is the boyfriend (and future husband, I hope) of my niece Sarah Zollo. Jared’s also a phenomenal musician. I know my dad would have loved the rightness of that.

Dad loved that I was a songwriter, and always encouraged me in what he knew was not an easy pursuit. At 12, he enrolled me in the North Shore School of Music for Saturday lessons in piano and music theory, knowledge which has served me well ever since. He’d drive me there and pick me up each week.

One of the greatest days of my youth was when my 8th grade music-teacher, Mrs. Bertagnolli, taught our entire glee club one of my songs, “Picnic Island,” to perform in concert. It was a daytime show, and my dad was there. And he was never there during the day, he was in the city, working, always. But on this day, he was there. He even taped it on a little cassette machine, a tape I have always cherished, as it has the performance of the song, and then, over the applause at the end, my dad cheering: “Yay Paulu!!!!”

Besides being a decent pianist, he was also a fairly good visual artist –and took painting courses, but never felt he could do it very well. One time, however, he drew me a rendering of a space alien, one of those little green guys with the giant eyes, but long before E.T. made that cute, and abductions were in the news. It so scared me that I ran away, crying. I think my mom got mad at him for that.

So instead of being an artist, he collected art. He always loved looking at art, he loved Chicago’s great Art Institute (“as great as any museum in New York,” he’d tell me). We went there together hundreds of times, and he was always in heaven.

He also loved galleries. Especially the Richard Grey Gallery and the Zolla-Leiberman gallery, both of which I frequented with him countless times. He was friends with everyone there, and delighted in discovering new artists.

Many times I’d have the great pleasure of going with him to an artist’s studio, sometimes after Sunday school at temple. I remember going to the studio of Larry Conaster. It was the first time I had ever entered a whole home of art like that – not an art collection – but a home devoted to creating art – and it was like viewing paradise for me. It showed me a life I had never considered, living in the suburbs of Chicago. And one my own dad celebrated and loved.

So when he could, he started buying art. Great modern art. By some of the greatest modern artists in the world, such as Hans Hofman and Sam Francis. And many of whom went on to great fame after my father first found them, such as Terence LaNoue and Anthony Caro.

He loved it that both of his sons married artists. He always loved talking art to my wife, Leslie, and going to galleries and museums always in L.A. every year when they would visit. Leslie painted him a very small, abstract blue monochrome square. And it was one of the great honors of her life when he told her it was as good as anything he owned. And we knew he meant it. He was not one to say something like that if it weren’t true.

Peggy, Peter and I all went to Sunday school in the city, every Sunday, a long and awful bus-drive from Wilmette each week. To make it more bearable, Poppa Ray would always meet us after with bananas, as we would be ravenous.

Many Sundays my dad would be there, and instead of riding the bus home, I’d get the great joy of going out for lunch with him. Some of my happiest memories were going to Old Town, as it was called then, on Wells. There was a cafe called Bowl & Roll which served only soup and bread – and the most amazing soup ever. Afterwards we’d stroll around, going into record and posters stores. For me, pure joy. He’d always get me a poster or a new 45.

I was with him in 1970, the first time I heard Simon & Garfunkel’s “Bridge Over Troubled Water,” the single of which preceded the album, and was being played over and over in this hip record store. Neither of us could believe what we were hearing; it was the most beautiful music I had ever known (rivaled only, I felt, by “Let It Be,” also released that same year.)

He bought me the 45, and I went home and played it over and over, endlessly. To this day, it brings me back to that store, that time with my dad.

He was a voracious reader who loved so many authors, especially Saul Bellow, John Updike and Phillip Roth. But he thought Hemingway was the best of them all, and modeled his own style on the short, concise sentences of Hem. In his later years, when Parkinson’s started to rob his memory, he told me he realized he’ d forgotten all the great books he read, so he could now read them again. That is so much my father. Finding the blessing even in the darkness.

I remember coming into his living room once, with hardly any light except a fire going. And he was alone, reading The Old Man and The Sea. By Hemingway.

He read everything. Back in the day when there were was an early and late newspaper, he’d get both – the Chicago Sun-Times and in the afternoon, the Chicago Daily News.

When there was tragic news, as there sadly often was in the turbulent Sixties of my youth, he’d alert us to it by showing us a headline. How I remember the darkness of that sunny day in June of 1968 when he showed us the headline that announced the assassination of Bobby Kennedy. Though I had never once seen my dad cry when I was a kid, on that day there were tears in his eyes. He also read several magazines, including Esquire, New York, Life and Time. But his favorite was the one he always considered the greatest magazine in the world, The New Yorker.

He shared with us, by means of genuine enthusiasm, his love of books. My sister Peggy, like me, became a constant reader. During much of my childhood, before she left for college, I remember her in her room, on her bed, reading.

Every Saturday we’d go to the Wilmette Library, and I would always check out two books. He would always review my choices, with genuine interest, and comment on them. There was no book unworthy ever. He read books always.

At night, when Peter and I would be on the floor in front of a TV, he would also monitor, from a distance, our show – whether “Bewitched,” “Bonanza” or our favorite, “The Dick Van Dyke Show.” But he’d also have his newspapers, magazines and books.

He rarely, if ever, watched TV without also reading. He’d sit, after dinner, with a cup of black coffee (any coffee not black, he said, was not real coffee), smoking his pipe. He smoked it most of our childhood until, to help my mother give up cigarettes, he also quit this, one of his greatest pleasures. But he did keep his collection of beautiful pipes.

He also respected words, and enabled the expansion of our vocabularies by always looking up dictionary definitions when needed. I remember watching a speech by Richard Nixon, not our favorite guy, but Dad taught me to pay attention.

Nixon used the word ‘rhetoric’ several times. I asked what it meant, and, as was his way, he said, “Go look it up.” The idea being that it was wise to learn derivation of words and context, and to know all the official definitions. He had the immense Random House dictionary always in the same spot. Now I have it here.

Another technique in expanding our word usage was his vocabulary list, which he kept in the kitchen, so that at breakfast each day we would learn a new word. He kept it in the same little notebook as our grocery list, teaching me early on that good words, like good food, will nourish you always.

We could bring in a word, and with the dictionary, he would define and use for us. Or he would introduce words himself. I prided myself on learning each one, and how to use it.

He also insisted that all three of his kids study Latin, so that we would come to intimately know where most of these words came from, and how our grammar was devised. I’d thank him with a joke, after many years of studying this dead language. If ever I go to ancient Rome, I’d say, I’ll be in good shape. He liked that one.

I learned humor from him, good comic timing. He was very funny. I remember being at the kitchen table growing up, the five of us, Mom and Dad, Peggy, Peter and Paul, and he would tell some story about his day, and have all of us in hysterics. It was the content, of course, but also his natural gift at telling stories. Great comic delivery. All of us would be dying with laughter, but especially my sister Peggy; I remember her waving her hands to tell him to stop, she couldn’t breathe!

He didn’t, however, like a lot of the humor I did, such as the Marx Brothers (“silly”) or Monty Python. What he did find the funniest of all was any humor about Nazis – “Springtime for Hitler” from The Producers by Mel Brooks was pure greatness.

But his very favorite was Peter Sellers’ portrayal of the wheelchair-bound Nazi in Dr. Strangelove, who could not restrain from giving a Nazi salute, though he tried, holding down his Seig Heil hand with the other. My dad imitated that a thousand times, and as a kid I didn’t quite get why it was so funny. I do now.

But there was nothing funnier to him than making fun of himself. Such as the Playboy joke: “I didn’t think it would work!”

Or the time he thought he could save money on barbers by buying a little barber’s razor he saw on late night TV, with which he proceeded to immediately carve a large bald spot right into the middle of his head. To cover it up until it grew back, he used shoe polish. Nobody found this funnier than he did.

Or for Peggy’s 16th birthday party, with 15 girls over sleeping downstairs in the family room, he decided to wake them by blasting, over the stereo, Beethoven’s 5th. This was one joke I found funnier than did my sister.

If ever a word was mispronounced by one of his kids when they were little, he’d used it forever. Monkeys were “meenkies.” For the rest of his life! Somehow midgets became “widgums.” But used so frequently, that I did not know widgum was not an actual word until I was about 20. One of his favorite words was “goob,” short for goober, which is short for goober pea. A goob is a not so smart person. He referred to himself, always, as a goob. With his grand-kids, I discovered, he became “Poppa Goob.”

He adored ancient puns, and loved to repeat them, the joke being that yes, we are saying this joke again. The funny part was not the joke, but that he would still be repeating these chestnuts he first heard around 1935. “Ever seen a horse turn into an alley? Have you ever seen butter fly?” Anytime you would mention the time 2:30 – he would say “Time to see the dentist!” – for tooth hurty. A very bad pun, but the repeated badness was, of course, great.

Our childhoods were peppered with his famous funny lines. Most famously must be the time at Grandma Clonick’s Seder dinner. The whole extended family around a long table. And suddenly the table began to collapse. But it did so very slowly: the entire thing just floated oddly to the ground, as everyone grabbed their dishes and glasses. Not one thing hit the floor, and nothing broke.

My dad made the first comment, to Grandma Clonick. “Mom,” he said, “I think you made the matzo balls a little heavy this year.”

He loved good wine and good food. As a kid he used to make great breakfasts on weekends – what we would call “Daddy’s goulash,” eggs with salami and/or hot dogs and cheese and other great stuff mixed in. Delicious. Or pancakes – but rarely in circular form. I remember one that was so far from circular, I asked what the deal was. “That,” he said, “is South America.”

He loved barbecuing in the summer, and good farm corn – always available in the Illinois heartland – was a separate course always, after the main meal. He was a messy corn eater, but he loved it.

He also loved my mom’s cooking, and she was a great cook. Once a year she would cook tzimas, a Jewish delicacy, which is a sweet beef stew that took so much work its name also means a big bother, as in “What a tzimas that turned out to be!”

But my dad loved her tzimas so much (always without carrots; he hated carrots) that he would always eat too much that he was almost sick, a feeling he forever called “the tzimas feeling,” and which he also attained with countless non-tzimas meals.

He loved ice-cream, and would buy an expensive very rich chocolate ice-cream calls Vala’s. But unlike tzimas, with ice-cream he never over-indulged, and would afford himself usually one spoonful – sometimes two – as an afternoon snack.

When we’d come in to visit from California, he’d always have great wine waiting. For a long time he loved Chateauneuf du Pape the best, and would have a bottle open and breathing, ready for us.

He was a funny and adventurous eater. He’d often order items connected to his youth with Poppa Ray, such as ox-joints, and always loved things we found repulsive, like sweetbreads. As a kid, I would almost always be willing to try his choice, and he loved my culinary bravery.

Eating was always a celebration for him, a reason to rejoice. As my brother Peter noted, he wasn’t the type to ever have lunch at his desk while at work. Instead, he’d go out to one of many restaurants he loved, and every night, at dinner, one of our stock questions was “Where’d you have lunch today?” And he’d tell us.

In rare instances, I got to see this good life up close. I’d visit his office with him during some school holiday (another amazing paradise to me, replete with modern art), and he’d take me out for lunch to one of his places.

Once we went to the 71 Club, which was in the Executive House. He got a roast beef sandwich called The Racer that was so delicious I couldn’t understand why he wouldn’t have it there every day. But the next time we went there, he introduced me to Eggs Benedict. And that, I felt, became the most delicious lunch in the world.

He loved the great restaurants of all the cities in which I lived. In Boston it was Locke-Obers, and he loved their lobster bisque the best. In Chicago it was Berghoff’s (where we’d stand at the bar, back before women were even allowed there, and drink beer – mine was Root), among so many.

And in Hollywood always the venerable Musso & Frank’s, which we’d frequent every time he was in town, and where he loved the history, the movie-stars we saw there (once Jason Robards and Richard Dreyfuss together, a double sighting!) and the tremendous food. He’d try everything on the menu.

In Wilmette, of course, it was all about Walker Brothers Pancake House, for the best pancakes in the world. His favorite – and mine, and my son’s – were the flapjacks, aka 49ers. We would go there with my son, and nieces and nephews. Of all the adults in our family, he was the one who would never miss going.

He loved Temple Sholom and the way all our families – his parents, Lois’ parents – all came together there. Like Poppa Clonick, whose best friend was Rabbi Binstock, my dad became best friends with the new rabbi who replaced Binstock – a man my dad, on the temple board, championed as the best man for the job, and lured from Minneapolis, the great Fred Schwartz.

He and Rabbi Schwartz became best friends. My father, as an only child, always felt he didn’t know how to make friends. So he had few. But the ones he had were very special, as they were genuine.

He and Fred were very close. Both deep thinkers, philosophical, serious readers. My dad did not like talking on the phone, yet with Rabbi Schwartz – and him only – he would talk a whole hour, sometimes more.

(The Rabbi preceded my dad in death, also from Parkinson’s, and I have the powerful feeling that he was ready and waiting at the gates of heaven as my dad arrived, first to greet him, show him around, and introduce him to everyone, including God. )

He became president of the Board of Directors of Temple Sholom in 1972.

When asked to provide a formal portrait to hang with the portraits of the others, he resisted the potential pretentiousness of the thing, and had a gag portrait taken. It showed my dad smoking his pipe, looking very serious, in a hardhat on which he drew a Jewish star.

As president, he refused to park in the presidential parking place. His proudest accomplishment was arranging for great artists to design beautiful stained glass windows s – Karel Appel, Miriam Shapiro and others – glorious, joyous windows which put the temple of the art map of the city forever, and which still shine beautifully on Lake Shore Drive.

He loved to drive fast. Though he had an Oldsmobile F-85 at first when I was a kid, when he could afford it, he started buying fun cars. His first was an AMX, an experimental car built by American Motors with a giant very loud engine. My mom hated it, but we loved it. Bright red with silver racing stripes, purchased from the automotive editor of the Chicago Sun-Times, Dan Jedlicka. I remember going with him to Jedlicka’s house in Evanston to see it first, and was delighted when he bought it.

After that he bought a silver Porsche 911, and a forest green Datsun 280Z. (How I adored that Datsun, as it became the car I often used in high school to date girls and drive friends. ) But he drove too fast, and got so many speeding tickets that if he was one away from having his license suspended.

Once we were heading home from the city speeding along the Outer Drive, close to the ground in that silver Porsche, getting pulled over by a cop. My dad, who rarely swore, said, “Dammit” very softly as he stopped the car, and the cop approached. He rolled down his window, and the cop came up, asked for his license.

“Okay, Burt,” he said, “do you know how fast you were going?” “It’s Mr. Zollo, please,” he said to the cop. Who says that? Evidently he had some issues with authority.

What a wonderful dad he was. Anytime I woke up crying in my bed with some night terrors or dark dreams, he would be there. He always came.

He was a great reader of books at bedtime, and also told great stories, many of which surrounded the naughty goings-on of a little girl named Josie Guggenheim. A little imp, she was based, I think, on Eloise of Plaza fame in NYC. She’d get on an elevator downtown and press all the buttons, or pour milk down the mail chute. That kind of thing. About which we would die laughing.

He’d wake us up with a song. He composed a “Good morning” song which he’d sing every day as he awakened his children, opening curtains, letting in the light: “Good morning… it’s time to get up!” This song would inevitably contain a weather report, as in “It’s snowing, it’s cold outside, it’s time to get up!”

I sing this same song to awaken my son, although, since we live in Los Angeles where the weather is almost always the same – sunny and beautiful – I still use my dad’s lyrics about snow and ice. To make it more compelling.

There were endless games of football in the street in front of our house, mostly “monkey in the middle,” which is three people – my brother Peter and Dad and me. Or ping-pong down in the basement. During the winter, with few other activities, we didn’t even need to speak to invite the other to a game. We simply used the silent universal sign for ping-pong, the hand gesturing as if in play.

We’d often bet on baseball games or some other contest which could be bet on. We would always bet for a milkshake from Peacock’s Dairy Bar, the closest ice-cream establishment there was. And no matter who won the bet, he’d always pay. And then there was “exploring.” It was a great game he devised in which we’d get in the car, and I would have the right to tell him which way to turn. And wherever we’d go is where we would go. A game I since played with my own son, a lot. A way of giving power, and fun, to a little kid.

He was always great at giving voices to my stuffed animals, and for some reason I can’t recall, we invented imaginary invisible elephants, who would always be about, floating – the main one of which stuttered for some reason his own name, which was “Lil-lil-lil Elephant.” He could always make me laugh hysterically, and I’d often do the same for him. He loved to laugh.

When I was 18, he and my mom took me to New York. He wanted to be the one to introduce me to the dreamland he knew as Manhattan, with its amazing hotels, restaurants, Broadway plays. The very first day we had lunch at The Plaza. “Now that we’re in New York,” he informed me, “we will see a lot of famous people.” Just as a joke, he pointed to a portly man dining, and said, “See – that is Alfred Hitchcock right there.”

He was just being funny, but the thing is, it actually was Hitchcock. I loved New York. In Chicago I once saw Forrest Tucker from a distance in a cafe, but that was the extent of my encounters with fame.

He encouraged me to ask for his autograph, which I did, as the great director was dealing with his bill. In portentous Hitchcockian tones, he said, “Just… let me… finish … my business here first.” I loved New York forever.

He loved to travel. He and my mom visited every corner of the globe, including many (such as India), that he loved and she so didn’t. I have a photo I love of the two of them aperch a giant elephant. My dad, for the only time in his life, had a beard that he let grow. And he was thin – he lost a lot of weight on the trip. But he was smiling. My mom, not so much.

He took thousands of photos on each trip, photos he had developed into slides that he’d turn into slide shows. These could be rather tiresome, but still we’d watch each one, because we knew he wanted to show us the world.

When we were kids, to avoid the winter, we went during several spring vacations to a dude ranch Tucson, Arizona. Which, for me, was absolute heaven, my first taste of the beautiful west. Sunny, warm when the rest of America was frozen under snow, and with exotica everywhere to a Chicago boy: horses, cacti, swimming pools, mountains.

Mountains! They were almost too great to believe. We’d just stand and gape at those vast mountain ranges, experiencing genuine awe for the first time.

Now I see mountains every day of my life, and always think of the first time.

For a full week, we’d play cowboy, ride horses, wear cowboy hats and boots, eat breakfast out in the desert, swim, luxuriate. My mom never once joined us for a horse ride. My dad never missed one. He loved it as much as we did.

My brother Peter, in fact, loved it so much that one night he promised me he would move there when he was an adult. Even then I felt it was a promise that would be unfulfilled. It wasn’t. After graduating from college in Iowa, my brother moved west, with his wife Debbie, to beautiful Tucson. (But just for a few years, then back to Chicagoland.)

My father was a humble man, and he encouraged it in his children. He told me in my music writing that it’s always better never to use the word ‘I’ – never draw that direct attention to the writer. Instead of writing, “Then I asked Bob Dylan…” one can write, “Asked about this, Dylan said…” Advice which I always followed, to shine the light on the subject and not the author.

Those times, in stories, when I needed to add a personal slant, and write about myself, it always seemed wrong, like swimming upstream to me. Even writing this, which demands a personal slant, it’s hard.

He didn’t even like it when I used the word ‘journalist’ for the work I did, though I was a music journalist, after all.

He was proud of my work, proud that I never gave up on pursuing interview with idols such as Simon and Dylan. When I attained my lifelong dream of singing a duet with Art Garfunkel (on my song “Being In This World” on Orange Avenue), he was thrilled.

He read everything I ever wrote. He listened to every song, every tape, every CD. And read every word of every book and magazine story.

I got him a subscription, of course, to every magazine on which I worked, and he would give me his feelings about each and every issue. When I published my first issue of SongTalk in 1987 for which I was editor, I sent it to him. He sent it back with ink all over it – comments on style, lay-out, content – everything. And all very smart details – he did it not to be critical but to help, and I took all of his advice.

Now with American Songwriter magazine for many years, I made sure he got every issue. And he would page through so as to be sure not to miss anything I wrote. I’d always have my column, but often other stories or reviews. He wouldn’t miss one. Whether these were about artists he knew –such as my lifelong idol Paul Simon – or some band he’d never heard of even once – he’d call to say, “The Soup Dragons story was excellent! What an interesting bunch. This is good work.”

Not only did he keep all my books that I wrote and sent, and those written by my brother Peter, he had all the reviews Xeroxed and taped inside the book covers. When we moved him and my mother out of their home, I discovered every tape I ever sent him, going back to my first year in college, 1977. Every letter. Every issue of every magazine. He was a man who hated clutter. But he saved every issue. That he wouldn’t throw away.

He was a harsh critic. Which could be tough, but was good for me. When I started writing songs at 11, he’d listen to every one. The key word he used was “trite.” As in, “that’s nice – but it’s been done. A lot.”

My entire challenge in life became to write something – anything – he didn’t think was trite. Because when he did like something, it was great, because it was true and I knew it.

I can remember still songs of mine he praised – songs I wrote when I was 13 or 15 or 18. I always remember one of the last times I played him some songs. He was so tired by Parkinson’s and the medicine he got that he’d sometimes fall asleep while I was singing to him. But this time I had just written the song “Baltimore” with Darryl Purpose. About the death of Edgar Allen Poe. A lifelong of avoiding ‘trite’ led me there, not likely song content. His only response was “Wow.” It was the best review I have ever gotten, to this day.

He was generous to a fault. In my adult years, he refused to let me ever pick up a check, or pay for anything, though I would try to do so sneakily. It was bad enough when we would visit Chicago, but I’d be in his world. But in Hollywood, I tried hard.

Once I had been given four tickets to a show at the Cinegrill in the Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel. Mind you, these tickets were free – but still had to be picked up at the box-office. I walked ahead to pick them up, as he was behind with my wife and mom. Suddenly, he thought I was about to pay for the tickets, so he ran – quickly – across the lobby of the Roosevelt, yelling at me to stop, stop! God forbid his son pay for anything when he was in town.

He never said a bad word about anyone. Or very rarely. There was one man he lent money to, not a small sum, who told my dad, quite coldly, that he would never pay him back. And it wasn’t the money as much as the ethics of that which really irked him. He told me about it, almost in disbelief, but didn’t castigate the guy at all.

Years later when we heard the news that this guy had died, my dad told me, and I said, “You didn’t like him much, did you?”

He laughed and said, “No. He was a bastardo.” He wouldn’t even use real English. That was close enough.

One time I told him about a friend of mine who was very crazy – officially so, bi-polar. This guy would go out of his way, when manic, to find something that would hurt me. One time he thought I lived in my dad’s shadow. (Which I do, to some extent, but happily). He’d read both of my dad’s novels, and proclaimed, “Your dad is a great writer, a better writer than you’ll ever be!”

He thought this would hurt me to the core, when in fact it had the opposite effect. I was thrilled he knew that my dad was a great writer.

I told my dad about it, of course, emphasizing the “great writer” part.

“Really?” he said. “Doesn’t sound so crazy to me!”

He loved my adopted city of Los Angeles. Maybe not as much as he would have loved me to have lived in New York City, his dream city. The city he looked up to from his famously second city, always wondering what would have happened had he lived there. He seemed a little disappointed when I told him I was moving, instead of into Manhattan, to L.A. But only for a moment, and then learned to love it here, and loved visiting every single year. And he knew visiting California in the middle of a Chicago winter, it’s a good and sunny tradition.

But it was always tough for me living so far away, in this Tinsel Town some 2000 miles west of home. The hardest part was missing life with him. In October especially, when I knew the trees in Illinois would be rich and ripe with changing leaves, I’d get especially homesick. I always loved Hollywood, well, most of the time, but I did miss the normal world, and I always loved autumn the most.

So to help me maintain, every October, he would walk all over Wilmette with his camera, and take photos of the foliage for me. Some of these would also feature family pets, and grandchildren, who were cute little kids then. I have hundreds of them. He kept doing it till it was too much work for him, and he allowed, “Well, they look the same each year. Just use the same ones.”

I told him that in October I missed him the most. He said, “I always miss you the most. All the time.”

He told me once what his dream day was. It was being home, working on a novel while a good tennis match was on, and going back and forth. Back and forth between work and recreation, the two linked. He found serious work fun and took fun stuff seriously. That was heaven for him.

So that is how I remember him: In his element, in his happy home, surrounded by beautiful artwork, his beloved wife never too far away – a fire in the fireplace – a great tennis match on TV – and a novel under way on the typewriter. He’s home – and as always – he’s happy.

That was a wonderful story!

thank you Gregory Clonick. Are you related to us? My grandfather AJ Clonick?

Yes we are related but I would have to ask my dad exactly how, my grandfather was Theodore Clonick and I think was Shirley Clonick’s brother.

Hi Greg! Sadly- Shirley died just last week. She was 97. But no, she had no brothers. There were three sisters, Jane, Shirley and my mom Lois.

Perhaps your grandfather was a brother or cousin of my grandfather, AJ Clonick. Just called my mother – who is the last surviving sister- she is 88 – but she did not answer. But I will find out. Makes me realize I am not sure – as I recall – he had a sister Theresa though I know of no brother. But I am on it!

Wonderful story, Paul. The Wilmette Historical Museum, of which I’m the curator, would love to have a high-res copy of that photo of 2209 Sandy Lane to add to our collection.

really? How wonderful.

I will email you Mr. Curator!

My father’s name was ZOILO.

There’s also a location in basque country named ZOLLO.

In case it would be of any interest to Mr. Burt Zollo’s son.

I worked for Burt in the early 70’s air The Public Relations Board. I remember the day Playboy went Public. Burt was out of the office the whole day. I knew he had gotten stock for writing for Playboy, but didn’t find out for years that he became a millionaire in that one day. I also worked for him when he began to work limited days a week so he could work on his Book! He was mad at me when I gave notice to move on to another job. But we talked it through and he calmed down. Life goes on, right??? We didn’t keep in touch through the years, but I’m sorry to hear of his passing and I’m sorry for your loss.