New Reviews

October 2011.

Chicago

October 22, 2011.

Saban Theater, Beverly Hills, California

By JEFF GOLD

Chicago rocks the Saban Theater! Chicago’s triumphant return to Los Angeles proved why they are one of the greatest and enduring bands in rock and roll. This horn based, hybrid band sounded as fresh as ever as they effortlessly performed rock history, song after song.

The first time that I saw Chicago was in 1977 after just graduating from college as a music major in New York. It was the original lineup with Terry Kath, the great guitarist that added an incredible edge to contrast the smooth horn section and effortless singing style of Peter Cetera. It was an amazing night of music. Now 34 years later I find myself enjoying again one of my favorite groups, and one that should be in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. I mean, hey, the Lovin Spoonful is in the Hall Of Fame!

I was really looking forward to reacquainting myself with all the songs and albums that have been such a part of the soundtrack of my generation .

The setting was the beautifully restored Saban Theater in Beverly Hills, a glorious art deco former movie palace.

The set opened with a great rendition of the full side of Chicago’s second album. When the lights dimmed and “Make Me Smile” began with that incredible sound of the horn section, I was brought back. Way back to a time when the quality of music was at such a high level. When “Color My World” started I had forgotten what a beautiful song it was. I did long for Terry Kath’s incredible voice, but the band did a valiant job in making up for his absence.

For the next 2½ hours we traveled remarkably through 25 hit songs, including classics “Saturday In The Park,” “Does Anybody Really Know What Time It Is?” and one of my all time favorites, “Beginnings.” They even did “ Rockin Around The Christmas Tree” from their beautiful newest album, a tribute to Christmas called Chicago XXXIII: O Christmas Three.

The original core of four musicians is still in place: Walter Parazaider on sax and flute, James Pankow on trombone, Lee Loughnane on trumpet, and Robert Lamm on keys and vocals. Lamm held the band together and gave it its soul. Drummer Tris Imboden was terrific and did a great drum solo on “Beginnings.” Keith Howland did a credible job on lead guitar but unfortunately nobody can replace Terry Kath. Jason Scheff held the rhythm section together with his solid bass playing, although not as strong as a vocalist; Peter Cetera’s shoes, like Kath’s, are hard ones to fill.

Lou Pardini on keyboards and Drew Hester on percussion were a welcome addition.

If you get a chance to see Chicago, GO! They’re a great American band, and sound as fresh as ever. I had a great time and it was a memorable night of music. And please somebody tell the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame to WAKE UP and induct the band with the second most chart successes of all American bands behind only the Beach Boys.

Marc & The Plattitudes

Bitter & Sweet

Produced by Lisa Nemzo * Dream Wild Records

By PAUL ZOLLO

This is a masterpiece, a chain of powerful songs beautifully produced and rendered. Marc Platt has been writing great songs and making powerful albums for years. But this a new level of greatness for him. This is as good as it gets.

“Songs should be sturdy,” Van Dyke Parks said. “They shouldn’t fall apart like a cheap watch on the street.” I thought of that quote while listening – and then relistening, many times – to Bitter & Sweet. These are songs written by a guy who understands the intrinsic architecture of songs. These songs are sturdy and solid, designed so they won’t fall apart on the street. Ever.

Like the greatest songs, these ones endure. Not only don’t they fall apart, they get better every time you hear them. They bring with them the happy reward of recognition, of realizing that yes, indeed, this is as good as I thought, this is as powerful, as cool and unexpected. It’s those little harmonic or melodic divergences, unexpected chord changes, for example, that become the very element that lends the song its power and longevity, and makes you want to hear it again and again.

Platt is well-known in Angeleno creative circles not only for the solidity of his own songs, but also for his vast knowledge and love of the pop-rock songs of past decades. He’s a guy who aims for the timeless in songs, those elements which make songs come alive at the moment, and for moments to come.

When songwriters produce other songwriters, the results are often especially compelling, as when Walter Becker produced Rickie Lee Jones, or Jackson Browne produced Warren Zevon. Songwriters know what makes a song tick, enhancing the specific strengths of the song as opposed to forcing them into predetermined production styles. Lisa Nemzo, long one of L.A.’s most revered songwriters, has produced these songs with copious and palpable love for what Platt does, lovingly framing the songs to underscore the strength of each. She started with an idea often considered arcane these days, that the song is the thing.

But it’s a good place to start when producing a songwriter such as Platt, whose songs are so cannily constructed that a producer needn’t invent new elements as much as focus and enhance what’s already there.

“Sucker’s Game” is a good example, with a great built-in rave-up rock swagger that the Stones could play the hell out of – though this great moaning electric guitar throughout is closer to Fripp than Keith Richards. Nemzo allowed the song to come to life in the studio, locking in a solid groove spiced by rhythm and lead guitars.

Nemzo also co-wrote three of the songs here, including the title track as well as the greatly affirmative “I Will Carry You,” which is at once both simple and complex musically, shifting through unexpected changes. The director Sidney Lumet said the goal of art is to achieve a perfection that isn’t obvious: “inevitability does not equal predictability.” It’s a wisdom that connects all these songs, which never seem contrived or arbitrary and yet are also freshly non-imitative. Like the best of songs, they break new ground with much loving respect for what’s come before.

It’s also wise to surround the songwriter with great musicians who know how to spark a song, and Nemzo did that, assembling a small group that does everything – even drums – as well as bass, keyboards, harmonies, guitars and more – all played by Platt and Nemzo along with Berington Van Campen, Keith Wechsler, Paul McCarty, Thomas Hornig, Jason P. Chesney and Dale LaDuke. (Dale is the only one on accordion.) The level of musicianship throughout is as elevated as the songwriting.

“Must Be You” is a little gem, a perfect song in less than three minutes. A lovely declaration of new love set to two acoustic guitars with sweetly sparse piano sparkles, it unfolds without a single false note. Its bridge is further evidence of an inspired, seasoned songwriter at work; like a classic McCartney “middle-eight,” it cuts away to a whole other scene before seamlessly returning to where we started.

“My Heart Needs Something New,” written with Patty Matson, is an ideal marriage of words and music, the title line sings with its music with absolute rightness, as if they both emerged together. It’s haunting and hopeful, bringing sorrow from past heartbreaks to meet up with a reason to believe.

“We Don’t Get Along” has a classic and visceral, electric Neil Young meets R.E.M. vibe. Solidly set to a folk-rock groove and stinging electric guitar, it’s a song about saying the unsaid, the stuff that can’t be taken back. It’s point of no return time, but lovingly – that the singer wrote such a poignant song is evidence of real love, wrapped much more in resignation than rage.

If Otis Redding worked with Steely Dan, it might sound a lot like “The Way It Has To Be,” which has a slick and snaky minor-key soul feel but with hip modern slant, another lovely fusion of the forever past with now.

Nemzo-Platt saved one of the album’s most powerful songs for the end. “Alone With You In A Crowd,” which they co-wrote, has a gloriously charged melody, reminiscent of the way Roy Orbison shaped songs to ascend and swell before exploding into an anthemic chorus. It’s classic build & burst songwriting with a deeply tuneful chorus that takes the title and runs with it. It’s one of those titles that says it all, and by being so eminently singable highlights the issue at hand – that what’s on the surface isn’t showing the whole story. It’s savvy songwriting, which with different music could seem contrived, and yet with the soulful purity of these chords and this melody is poignantly dimensional and delicious. It’s an ideal candidate for a new theme song for so many who have felt this exact emotion and yet never had a song to define it.

“The Life I Wanna Live” opens the album with a dramatic pulsating orchestral arrangement built on the rhythm of the chord changes, like a Brian Wilson track, with the drums (played by Nemzo) delicately commenting on the situation rather than dominating it. It’s a powerful opener, with Platt’s voice as clear and resonant as Willie Nelson singing about blue eyes crying in the rain. His vocals throughout the album, wisely mixed so as to clearly project the lyrics, are confidently soulful.

These days musicians often don’t think in terms of albums anymore, leaning towards producing singles for downloads. But there’s an unmistakable power in the momentum of a great collection of songs, how they sound in sequence, and the emotions created by hearing the whole rather than its parts. This is one of those albums, like the ones we listened to forever growing up, of strong songs connected by a singular energy and vision that lingers long after the music is done. My plan was to listen to this just a few times so I could review it, but I found myself wanting to hear it over and over, which is a good feeling in these disposable times in which there are more albums than ever, but fewer good songs.

We’re in an age in which technology enables artists to create remarkable sounding stuff even when there’s little there in terms of an actual song, something of substance. But when artists start with a real song – and craft substantial, inspired work before making the record – the consequence is something far more dimensional and moving than sonic confection. It’s something designed to last. And it reminds us what songs can do. Platt is someone who has never forgotten this truth.

So take the time to listen to this. You’ll be glad you did. Music this good matters. –P.Z.

James Lee Stanley * Backstage at the Resurrection

By PAUL ZOLLO

James Lee Stanley, Backstage at the Resurrection. [Beachwood Recordings]. Inspirational, inventive and inviting. A great achievement. Just when we think James Lee Stanley won’t ever record a new album as great as one of his past classics, he comes along with something like this, a collection of poignant, charged songs by one of our greatest singer-songwriters. He’s long been a beloved presence on the L.A. folk music scene as well as throughout America with good reason: not only is he a gifted and original songwriter, he’s also one of the best singers and guitarists around, with a voice that just takes flight in songs. Produced and arranged by Stanley, the tracks are rich with the love of great musicians with whom he’s performed over the years, including Chicago harmonica legend Corky Siegel, trombone and bass by the great Chad Watson, Bill Kole on banjo, John Batdorf joining Stanley on acoustic guitar. But it’s the harmony vocals throughout that raises this one far above the level of most current projects. The man knows harmonies – and also knows lots of the best harmony singers around, who are enlisted to grace these songs, including Dan Navarro, Lisa Turner, Severin Browne and Joe Rathburn. “Backhand Man” sounds like a new standard, cushioned by rich, often complex harmonies and sparkling acoustic guitars. It sounds like one of the best Byrds songs you’ve never heard. “I Can’t Cry Anymore” is an infectious testament to persistence and strength, the kind of song we need now more than ever. Throughout Stanley cannily merges jazzy harmonies and chords with great soul, as on the glorious “Don’t Wait Too Long,” a stunner with the kind of close jazzy harmonies CSN can only do cause of David Crosby’s vocal genius, and Stanley shares this dynamic. Humans love to hear harmonies, and when voices fold into harmonies this richly conveyed, it introduces a wonderful depth – a whole other dimension – to a song. Backstage at the Resurrection is yet another chapter in a remarkable career; one of the best albums I’ve heard in a long time by a guy who has been making great albums for a good while. www.jamesleestanley.com

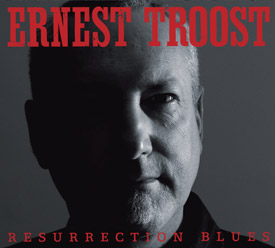

Ernest Troost, Resurrection Blues. [Traveling Shoes Records]. A delightful journey down rivers of new blues & folk from this Kerrville New Folk Winner. New Folk is a funny idea, as Folk’s always been about not what’s new but what’s true, a truth often polished with time like sea-shells in the sand. And yet it’s a term that fits Troost’s happily heady merger of traditions; he writes songs that resonate with the pure authenticity of traditional blues and folk, like songs which have been around, maybe passed down between generations – they got that immaculate shine & polish on them – and yet with a great freshness and verve that only emerges when a songwriter connects with something new. Produced by Troost with Louise Hatem, it’s got an understated warmth throughout that wraps these songs just right: Troost is a multi-instrumentalist who cooks up nice tracks of guitars, mandolins, bass and percussion he plays himself. His work reflects Woody Guthrie’s axiom that any damn fool can be complicated, but it takes genius to attain simplicity. It also takes a certain measure of courage in the context of modern times. His lyrics blend wistful humor, gentle resignation and the kind of enduring folk wisdom which has made great songs great for ages. These songs aren’t confection; they’re not synthesized, looped, or digitally manipulated. This is about real music, things of substance, as he expresses ideally in “Real Music,”: “Real music got a mind of its own/Real music is blood and bone.” Indeed. www.ernesttroost.com

Lisa Donnelly, We Had A Thing. An amazing album, truly. A delightful and unexpected musical journey pioneered by an extravagantly gifted artist. Great and genuine songwriting, beautiful and heartfelt singing, and tremendously inventive production. Lisa Donnelly’s a deeply expressive songwriter, and creates songs of human experience, tinged with hope, wisdom and pensive humor. The irrepressible “Laugh” is one of those special songs you never forget after hearing just once; spiritual and earthly at the same time, as are all these songs. “Laugh” and others contain colors of ecstasy, the bliss attained when connecting one’s heart directly to a melody and a lyric. Delivered with great verve and purity, it’s a momentous song, something which deserves pulling the car off to the side of the road to listen to so as not to crash. The album’s produced beautifully by Rob Giles with Rich Jacques and John Morrical, who create nice grooves sparked by a fun freshness, with unexpected divergences that keep the listener tuned in. Lisa’s range seems unlimited and unchained both as a songwriter and singer: “Little Devil” is delightfully and devilishly funky, and she sings it with the soulful authority of Etta James riding out great waves of soul, while “Stuck In A Rut” has a soaring, yearning Roy Orbison dynamic as performed by k.d. lang: it’s soul, it’s country, it’s rock and roll, and it’s all connected by the sheer force of her willful soul, bending the notes with a purity of intention that’s both startling and nourishing. This is one for the ages. www.lisadonnelly.com

Paul Simon, So Beautiful Or So What. [Concord]

Paul Simon, So Beautiful Or So What. [Concord]

YEARS AGO HE SAID HE WAS more interested in what he discovered than what he invented, a bold statement coming from this most inventive of songwriters. Yet it’s clear he’s been on a journey of discovery for years, and lucky for us all, it’s far from over. Decades beyond the point at which most of his peers peaked, Paul Simon is still discovering new ways of writing and conveying amazing songs, discovering beautifully unexpected and often spiritual language, as well as new rhythms, melodies and instrumental textures, to create a brand-new epic of great songwriting proportions. If you’re one of the many millions of living humans who have been touched by this man’s work at some time in your life, you’re in for a treat, this is a pure delight.

At a time when most of his contemporaries don’t even want to look at the new digital technology that has revolutionized the state of recording art – ProTools, loops, samples – Simon embraces them. Rather than traveling around the globe to stir exotic sounds into the mix, this time around he’s traveled into the past. When B.B. King told him to check out the Golden Gate Jubilee Quartet’s records from the 1930s, Simon grew so enamored of the gospel vigor of their vocals that he wove their voices into the track of “Love and Blessings,” which also features the sweet harmonies of his teenage daughter Lulu Simon.

Similarly, on “Love Is Eternal Sacred Light,” there’s a great locomotive-charged harmonica exhortation by none other than Sonny Terry, sampled from his 1938 “Train Whistle Blues.” The title song “So Beautiful Or So What” hinges on an acoustic guitar loop that echoes Simon’s own famous “Mrs. Robinson” riff, while the remarkable opener, “Getting Ready for Christmas Day” is woven lovingly around samples of a sermon delivered in the year of Simon’s birth, 1941, with much fire and musical brimstone by the Reverend J.M. Gates and congregation, and merged with a wonderfully funkified acoustic guitar figure and tender harmonies by Mrs. Simon, Edie Brickell. (Word on the wire is that the two have been working on an album of duets; I hope it’s true.) These are dimensional sound-collages both raw and refined, something we’ve never heard before, but instantly inviting when we hear that voice we’ve known for so many years sounding – as others have noted – as young as ever.

Back in the day, the presumption that Simon was playing on the same field as his peers – be it Dylan, McCartney, Neil Young, etc. – seemed sensible. But as the decades have passed, it’s become evident that he’s very much on his own field, playing his own game according to his own rules. Though his proximity to an acoustic guitar has caused many to consider him a “folk singer,” or “folk poet,” as USA Today dubbed him just last week, this is, in fact, a guy who defies any simple categorization. He had a rock & roll hit before the days of Dylan (with Garfunkel as Tom & Jerry, they scored with “Hey Schoolgirl” while still in high school), and wrote folk-rock epics like “The Sound of Silence” and “The Boxer,” while displaying a prodigious gift for rich melodicism – “Bridge Over Troubled Water” was as brilliantly tuneful as any Gershwin standard, and so majestically melodic that great tunesmiths like McCartney and Brian Wilson were stunned by it. (McCartney said “Let It Be” was his attempt to reach the level of “Bridge.”) “El Condor Pasa,” written to a Peruvian track by the band Urubamba in 1969, was his first conscious foray into combining American thoughts with music from beyond our shores, and also of writing track-first, the method by which he created Graceland and all of his subsequent albums until this one.

His solo albums reflected more explorations in sound expression, connecting journeys to Jamaica and New Orleans with the heartbeat of New York City. Songs like “American Tune” and “Still Crazy After All These Years” elevated the American popular song to a new level, breaking through prevalent pabulum and recycled dross murking up the airwaves to deliver something fun, fresh and often profound. “Late In The Evening” from One Trick Pony telegraphed the ecstatic rhythmic excursions that were to follow. Hearts and Bones contained some of his most sophisticated and successful songs, from the heartrending title tune to the surreal masterpiece “Rene and Georgette Magritte (With Their Dog After the War).” It also contained not one but two songs about an overactive mind (“Think Too Much A” and “Think Too Much, B,” the latter of which also reached that place from which Graceland emerged, a place of stirring rhythms matched with heartful melody – both complex and simple simultaneously.) Then came Graceland and its maybe even more brilliant companion The Rhythm of the Saints (which includes “The Cool Cool River,” sonically and lyrically one of his most dynamic and ingenious songs). The Capeman, a Broadway musical written with the poet Derek Walcott, was initially panned, as was Gershwin’s Porgy & Bess, and like that work, it’s already been rediscovered and reinvented as a beloved American folk opera, replendent with great Latino grooves and angelic doo-wop strains of his childhood.

His previous album, Surprise, was co-produced by techno wizard Brian Eno, and contained staggering songs such as “Wartime Prayers” and “How Can You Live In The Northeast?” which showed Simon not only connecting as powerfully as ever with his singular muse, but also embracing the new sonic possibilities Eno introduced to give this album a unique and unprecedented blend of acoustic and techno. That it wasn’t even nominated for a Best Album Grammy was hard to believe, as it was far and away the best album of 2006.

So for awhile, the revelation that Simon wasn’t even playing the same game as that songwriter with whom he’s been most often compared, Bob Dylan, led to the conclusion that he was really working much more in the world of Irving Berlin – like him a savvy Jewish New Yorker who had hits in almost every genre, and continued working well into his 90s. But the truth isn’t quite that – Berlin stopped challenging himself and became a relic of a previous era, whereas Simon’s journey now seems to have a vast and irrepressible arc, showing that he’s really much more akin to Picasso – an artist who changed the world of art with his own work while always moving on to new possibilities and new masterpieces into his tenth decade, never repeating himself. Paul Simon, I think it can safely be said, is the Picasso of popular song.

More than any living songwriter, he has discovered that crucial balance that songs can contain better than any artform, that of language both conversational and poetic; his songs are often very serious and quite funny at the same time. He speaks in the language of the streets and the language of the angels concurrently, proving again and again that the only limit to what a song can do is the songwriter’s own imagination and ambition. When I asked him years ago if writing songs to existing tracks, as he did with Graceland, was not a very tough challenge, he said, “Sure it is, but whoever said songwriting is easy?” And in that answer lies perhaps the secret to his ongoing success – the man has no reservations about working hard. In fact, he seems to love it. “I am still absolutely enthralled with songwriting and record-making,” he said. “I’m just glad they let me still do it.”

More than any living songwriter, he has discovered that crucial balance that songs can contain better than any artform, that of language both conversational and poetic; his songs are often very serious and quite funny at the same time. He speaks in the language of the streets and the language of the angels concurrently, proving again and again that the only limit to what a song can do is the songwriter’s own imagination and ambition. When I asked him years ago if writing songs to existing tracks, as he did with Graceland, was not a very tough challenge, he said, “Sure it is, but whoever said songwriting is easy?” And in that answer lies perhaps the secret to his ongoing success – the man has no reservations about working hard. In fact, he seems to love it. “I am still absolutely enthralled with songwriting and record-making,” he said. “I’m just glad they let me still do it.”

This time around, as mentioned, Simon has returned to his original method of writing songs – composing them at the guitar – just voice, instrument and a yellow legal pad. (He’s written only one song at a piano during his entire career, “Nobody.”) This is the man writing songs at his guitar, and it’s there that much of the most urbane and remarkable melodicism of the past decades was conceived. Though traditionalists cling to the belief that great melodies can only be composed on piano, Simon – along with pals Lennon, McCartney, Joni and few others – has long contradicted that archaic notion.

And what we get is simply stunning. “Love and Hard Times” is not only one of the most beautiful songs he’s personally penned, it’s one of the most stunning songs ever. Sumptuously beautiful, it’s his most poignant love song since “Hearts and Bones” (excluding “Father and Daughter” from Surprise, since it’s not about romantic love). Musically it’s quite complex, and it takes a few listenings to fully grasp the splendor of its melodic and harmonic beauty. Like a Joni Mitchell song, it might seem asymmetrically divergent at first, but it’s because new ground is being broken here – we’re outside of the conventional vocabulary of rock and pop melodies and simple progressions. But give it a chance, and it’s those very divergences which resonate most deeply, those odd turns of phrase which delight a little more each time.

Simon thanks the composer Phillip Glass on the album for knowing “how to untangle the harmonic knots that I occasionally miscreate…” It’s probably a good guess that this is one of the songs he’s referring to, as the convolutions of fragmentary chords and passing tones in which a composer might get entangled is evident. But whether it was with or without Glass’ assistance, this is an astounding achievement. The melody is rich and pure, achingly touching while also disarmingly colloquial. It opens on God and “his only son” checking in on the planet but needing to duck out quick because, like an artist forever obsessing on his latest work, their obligations are also ceaseless: “There are galaxies yet to be born/creation is never done.”

Unlike all the other tracks, this one is built only on the foundation of Simon’s exquisite acoustic guitar work, and is bolstered by a gloriously inventive orchestral backing arranged by Gil Goldstein that brings to mind McCartney’s collaboration with George Martin. Though Martin did the heavy-lifting when writing orchestral arrangements – notating and arranging all the parts – you know McCartney was in there singing his ideas. In the same way, Simon sheds some light on their collaboration in his thank yous, in which he commends Goldstein for spending an “inordinate amount of time with me thinking about and notating the ideas that he eventually incorporated so beautifully into his orchestration. “

The song, which seamlessly connects the divine visitation with the singer’s own romantic journey (“I loved her the first time I saw her,” he sings, adding, “I know that’s an old songwriting cliché.” ) concludes with a recognition of that which sustains us through these soul-battered times, the simple grace of a loved one’s touch. When he sings “Thank God I found you in time, thank God I found you,” it’s one of the most moving moments on any of his albums, especially cognizant as we are of his longtime marriage to Edie Brickell, and their raising of three kids. (On his first solo album, back in 1970, he posed the question: “Can a man and a woman live together in peace?” in the song “Congratulations.” Seems he’s found the happy answer.) It’s a musical and lyrical culmination that brings to mind the end of “Hearts and Bones,” which similarly ends a romantic narrative with the simple splendor of a perfect line. Unlike “Hearts,” however, this one has a happy ending. Were it only for this one song, this album would be well worth the price of admission. But there’s much more.

In these songs, as in life, there are far more questions than there are answers, which seems to suggest that his attitudinal edges have softened over the years. The guy who was often categorized as dour, reminding us our lives are forever slip-sliding away, shifted into recognizing there is a “reason to believe we all will be received in Graceland” and now has composed an album contemplating spiritual questions of God and man in almost every song. When I asked him – back in 1993 – if his feelings about where life leads has shifted, he said he didn’t have one single attitude, and presenting both sides of an equation is often more interesting – and always closer to real life. The very title of this title song is a question about life, and the meaning we attach to our existence, and within the song other heady questions about the human condition emerge: “Ain’t it strange the way we’re ignorant,” he asks twice, “how we seek out bad advice?”

“Amulet” is an achingly beautiful acoustic guitar instrumental which is as lyrical as anything he’s written, even without lyrics. It’s his first recorded solo guitar outing since his rendition of Davey Graham’s “Anji” back in 1966 – and it goes straight to the heartstrings as it brings back shades of bygone Bookends days, days of “Old Friends,” with its warm Satie-like guitar colorings, his harmonies adventurous even then. This is a good example to the uninitiated the full breadth of the guy’s musical prowess, combining melody and harmony with easy and fluid grace. Leonard Cohen has always joked about himself that he has “only one chop,” and indeed most great songwriters are not great instrumentalists. But as musicians know well, Simon’s got serious chops, and on this record, much more than recent ones which have featured other astounding guitarists such as Vince Nguini and Ray Phiri more than himself, the playing is mostly his – on both electric and acoustic – and it’s glorious.

“Amulet” segues directly into “Questions For The Angels” which is all about questions for God – or for God’s representatives. But never presenting a simplistic equation, Simon questions the very premise of the song itself: “Questions for the angels/who believes in angels? Fools do.” Later in the song, however, he identifies himself as one of the faithful fools. Built on a vibrational bed of acoustic guitar, marimba, celeste and harps, it’s a new song for the asking. It starts with a young “pilgrim on a pilgrimage” heading out of Manhattan on the Brooklyn Bridge, passing the sleeping homeless with some serious and fundamental questions about man’s place in this world. Simon dodges any sugary New Age sentiment with injections of levity, breaking the narrative with a brushes-on-snare waltz-time confrontation with the mammoth image of the rapper Jay-Z hawking clothes on a billboard. This is the world we’re living in – a world of celebrity commercialism all about now played against the eternal expanse of questions forever in the mind of man. Uttered in language gentle and colorful enough that it could appeal to the unbound imagination of a child, and sparked by a beautifully chromatic shift on the chorus, it questions man’s place in nature:

“If every human on the planet and all the buildings on it

Should disappear

Would a zebra grazing in the African Savannah

Care enough to shed one zebra tear?”

From “Questions For The Angels”

By Paul Simon

“Dazzling Blue” seamlessly fuses Indian percussion with American bluegrass as provided by Doyle Lawson and his band Quicksilver, while “The Afterlife” – which turns out to be much like a DMV for souls, requiring standing in lines and filling out forms – is energized by the dynamic rhythm of Simon on 12-string guitar.

The forementioned “Getting Ready for Christmas Day” is set to a great stomping groove, as is “Love Is Eternal Sacred Light,” which cooks with great gospel fervor, and is Simon’s most direct statement on the spiritual timelessness of love. With a title that seems straight from a Baptist hymnal, it’s a remarkable song, relating in delightfully succinct verses the very origins of life that God and Jesus are tending to in “Love & Hard Times.” He gives us the evolution of man and earth, all in two short verses, leading from the rural rightness of nature into the age of the machine, and ultimately the political dissonance of modern existence:

“Earth becomes a farm

Farmer takes a wife

Wife becomes a river

And the giver of life

Man becomes machine

Oil runs down his face

Machine becomes a man

With a bomb in the marketplace…”

From “Love Is Eternal Sacred Light”

By Paul Simon

“Love and Blessings,” which opens with a mournful moaning riff that sounds like fretless bass (but is most likely Simon on “Moog guitar,” as credited) and later veers off into a celebratory Dixieland clarinet flourish, provided by Dr. Michael White, is another tale of love and spirit, but one ever conscious of the world around us, and how we’ve poisoned it. As with “Can’t Run But” from Saints, which touched on the Chernobyl disaster, this one obliquely comments on global warming, recognizing that neither love nor spirit separate us from our home, our planet.

In this day when people download singles and rarely even purchase whole albums anymore, Simon’s reminded us that creating an entire collection of new songs is as much of an art as making a great single, and the album flows from song to song with a sweet inevitability that echoes the great listening experiences of previous decades – be it Abbey Road, Blood on The Tracks, or Still Crazy After All These Years. The momentum and depth of these tracks each enrich the others, and as beautiful as each song sounds alone, that beauty is deepened by hearing them as part of this musical narrative, not unlike separate movements of a symphony that only make complete sense when heard as part of the whole. In a world where it seems everything seems to be getting cheaper, more disposable and breakable than ever, and where beauty seems to be a diminishing resource, Paul Simon continues to make records like this one that enrich our world, and connect us with recognitions of our own human faith and foibles. It’s another masterpiece from the Picasso of song, an artist ever evolving, ever expanding the promise of the popular song.

![]()

The Fuxedos

By PAUL ZOLLO

HAVING BEEN A FAN of this remarkable band for several years, I expected something great from them. But this is beyond expectations. It’s one of the most audaciously inventive albums of all time. Just the version of “I Want To Hold Your Hand” should earn them their own permanent gallery in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame (although I suspect Cleveland might have issues with the band’s moniker). This is music both visionary and visceral, both hilarious and very serious, and it’s welcome now more than ever in this instant-message sensibility of modern lives, where people seem incapable of attending to anything that takes more time than a text or tweet. Here’s an album that is the evident consequence of vast and inspired studio hours, the kind of exhaustive craft pored into Beatles records as well as those by Brian Wilson, Steely Dan and Frank Zappa. A spirit of wildness permeates the proceedings, but it’s underpinned by a richly defined dimensional musical complexity. Yes. This is about passion.

First time I saw The Fuxedos live in Hollywood – in a now defunct vaudeville series– it was a revelation – amongst snake charmers, burlesques babes, chanteuses, comics and smirky magicians come The Fuxedos – led by a fireball of operatic rock and roll showmanship, style, and genuine hilarity named Danny Shorago. Who knew something this smart, this funny, this hilarious – all set against sparkling, shifting strains of rock-jazz-lounge-exotica – existed right here in Los Angeles? Though certain streams of brilliantly odd and ambitious songs seemed to have vanished ages past with the losses of Zappa and Beefheart, in The Fuxedos this spirit shines. An ironic demeanor informs their songs, which – like his – are often hilarious and serious at the same time, wedding sardonic and surreal lyrics to viscerally virtuosic music.

Danny Shorago is the lead singer and guiding spirit of the band. Onstage, he’s a wonder to behold, fusing soulfully fluid James Brown-like dance moves, a whirling and grinding dervish in a dizzy and surreal array of donned masks, hats, flags, guns, faux farm animals and more. In any one song comes a virtual encyclopedia of showbiz guises, from silent movie schtick to post-modern Goth bleakness to sham lounge lizard to heavy metal dude and beyond, all in the span of a single song. The band plays tightly rendered and multi-tempo music with abrupt time shifts perfectly synched to every Shorago move. He’s a dazzling dancer – with strands of Jagger, James Brown and MJ merged with Bill Murray, Red Skelton, Groucho Marx and Lenny Bruce.

So when I heard the band was in the studio recording their debut disc, I worried that they’d never be able to attain on record the unchained fervor and comic spark of their live shows, which rely heavily on visuals, live energy, and the spontaneous hilarity and brilliance of Danny. I was hoping for maybe just a fairly close facsimile of a live show – hopefully sans distortion. What I got instead is phenomenal – an album as infectiously inventive and wildly unpredictable in its production and studio craft as the band’s live onstage performances. It evokes the spirit of Zappa in a multitude of ways, not the least of which is that the comic abandon of live shows was always anchored in immaculately tight and virtuosic musicianship by the band. Like Zappa also, the music of the Fuxedos is groove-based – like any good rock and roll band – only their grooves constantly shift in unexpected ways.

But this is so much more. Danny and the Fuxes have created something in the studio as intense as their live shows, but quite different. Produced and arranged by Shorago, it’s a record that supplants the manic visuals with the full blossom of the band’s great musicianship; the self-generated inspiration of live performance blossoming instead into great studio inventiveness. Onstage there’s an ongoing clash – albeit an amiably intentional one – between Shorago’s unbroken theatrics and the earnest musicianship of the band. This is equaled out on the CD, where the music comes first. Like The Beatles, who poured the full force of their ingenuity into recording when they stopped performing live, exploring all the facets of multi-track recording and inventing new ones, Danny and company have come up with brand-new and invigorating ways to present their songs.

Shorago surrounds himself with musicians of the highest caliber. Drummer Ryan Brown shines here, as he does live, in his fluidly seamless shapeshifting of grooves, often several times within a song, and the solid, muscular soul of his playing. Like Charlie Watts, he’s a powerhouse rock drummer with the finesse of a jazzman, bringing in remarkable nuance while also being the engine for this ship. Multi-horn man Alex Budman, a prodigious jazz saxophonist who also adds flute and clarinet to the mix, lends explicit dynamism to each track, and like Brown is a rock player with the nuanced complexities of jazz. And Wes Styles, who plays all the guitars here plus some sitar, is an astounding guitarist who plays dazzling and often ferocious leads as well as orchestral rhythm parts. Add to that the excellent Steve Charouhas on bass – as well as Dan Andrews on sousaphone, Matt Lebofsky on keyboards and more – and you have an ensemble with evidently boundless possibilities. All of which Shorago explores and exploits with devilish flair.

The history of popular music from about 1956 to the present is surveyed in the most astounding rendition of The Beatles’ “I Want To Hold Your Hand” ever recorded. Crazy purists might even find it scandalous, and I wish they did to the extent of massive CD burnings as few things are better for record sales (something the lads from Liverpool understood themselves). Live, this is hilarious and great, taking the famous record through about twenty different musical genres, each completely committed. But here in the studio, they’re able to completely produce each genre segment with delightful fidelity. Starting close to the bouncy pop groove of the original they soon veer wildly off track into a Mr. Toad’s Wild Ride through popular music genres from about 1964 forward and backwards. Before the end of the first verse it ignites into speed metal and from there punk, power stutter, reggae, goth-metal, expansive “Revolution #9”-like demonic collage, Johnny Cash-like country, and Brubeck jazz-swing. It’s dizzying and crazy, and like a good rollercoaster, there’s nothing you want more when it’s over than to get back on.

This is an album designed to last. Unlike mucho musical confection we find littered throughout our culture, meant for fast food consumption and with the half-like of a gnat, this is a journey of symphonic discovery. This isn’t background music, though I guess it could serve as background music if you work in a bordello run by carneys, perhaps, or at the Nixon library (where the Fuxes have performed on several occasions). This is a rocket-ship shot directly into the heart of surrealism, in a world where Mickey Mouse is suspect while both Scooby & Scrappy-Doo exist within a milkshake. But examining these topics is like the countless Zappa reviews that would share only his words, without touching on the divine complexity of his music. This is a movie that needs to be seen to be understood, an experience that on the surface sings of the strange, mixing as it does assorted nuns with robot vampire wombats, cartoons, cephalopods, cowboys and more. It’s a little Fellini, a little Lynch, a little Lenny Bruce by way of Perry Como, resting at last on the odd figure of Mimsy, a frightened little girl in party dress and hat who represents the scared child in us all, the child alone in a world of ever-increasing madness, clinging to the frail hope of a little melody – a tiny portion of order inside chaos.

So if you’ve been looking for something new and musical that can make sense of the ever-shifting, ever-expanding panoply of too much of everything at once and not enough time to take it in, look no further. You need this album. And not just one song. You need the whole album. And if The Fuxes come to your town – you might not want to tell you mother. Or even your husband or your wife. But get there. You won’t be sorry.

![]()

Canyon of Dreams

The Magic and the Music of Laurel Canyon

By Harvey Kubernik

Photographs by Henry Diltz & Nurit Wilde

Design by X-Height Studios/Cecile Kaufman

Published by Sterling Publishing, October 2009

Hardcover, 384 pp, ISBN 9781402765896

By PAUL ZOLLO

A triumph. That this review is being published now and not closer to the holidays, as intended, is testament to the fact that this book is so richly absorbing that I needed to spend weeks just taking it in. It’s one of those books you know you’ll be dipping into forever, and never cast aside. Even without the text, this would be well worth it for the sumptuous and poignant visuals, which are stunning. But this offers so much more. An expansive love-letter to Laurel Canyon, it’s told with the authority and pride of an insider – but not just any insider: music journalist-producer-historian Harvey Kubernik has long been one of the most insightful music scribes around. His devotion to this unique history shines through these pages in the exhaustive entirety of information conveyed here so lovingly, delivering a happy and sprawling compendium of all things Laurel Canyon – the music, the history, the women & children, the color, the myths and the truth.

An enthused and gifted historian, Kubernik cleanly slides through the particular geographical and historic Hollywood origins for Laurel Canyon as an artists enclave in the midst of a metropolis. He gently unfolds and reexamines the myths and facts of this place in all directions, giving us the expected cast of characters (such as Joni, Jackson, CSNY, Eagles) but also the vast assortment of characters that intersected the canyon through its storied generations, from Houdini to Zappa to Slash. He takes the legends of the canyon and explodes them in every direction at once, unrestrained by the limits imposed by so many, that Laurel Canyon existed somehow only during the late ’60s and early ’70s. Kubernik gets what Laurel Canyon was, is, and will be, and teaming up with photographer-extraordinaire Henry Diltz cinches the deal, because nobody ever got better or more joyously intimate photos of the canyon and its denizens than did Henry, whose love for its spirit equals the author’s.

Gloriously designed with flowing text and images overdubbed with assorted posters, tickets and other musical mementos, it‘s not unlike Laurel Canyon itself, in that there is one main thoroughfare but also many side-streets, each affording delightful vistas. We get a page on Graham Nash’s remembrance of writing “Our House,” for example, or one on Henry Diltz poignantly remembering the catalyst of the canyon, Cass Elliot. One can get lost in this book as one can get lost in the canyon on a crystalline January day like today, a day in which the rest of America is blanketed in snow and here the light sings with orange-blossom sweetness. Canyon of Dreams is a timeless paradise in print, a spiritual refuge from all that is fleeting and trivial about modern times. In the kaleidoscopic colors captured by Henry’s lens, in the photos of the famous and forgotten, in the clear focus and friendly prose of the author, here lives that spirit which flowed from soul to soul in these heady days long before the advent of “social networking.” This isn’t the typically disconnected patchwork narrative of the time, in which all the characters are on separate paths, but an encyclopedic amalgamation of all the side streets, secrets stairways and unpaved paths which connect its inhabitants and their stories. And unlike all the scribes who came before to mythologize the canyon, ending their story with the emergence of the Eagles, Harvey extends his story through the immediate aftermath of the seventies and up to the present. He makes connections rarely made, such as Slash’s canyon lineage and emergence with Guns & Roses.

We get the great bands from here that became world-famous, like the Doors and Eagles, as well as those that didn’t, such as the Seeds. We get the icons like Jim Morrison but also the relatively unsung geniuses such as Van Dyke Parks. We get the artists and the women they loved, most sweetly Nurit Wilde, a photographer who was romantically linked to Michael Nesmith and others, and who glows in luminous photos taken by Diltz. In her image is crystallized the essence of the canyon and this book, the sense of promise, of youth, of romance.

The tragic heartbreak of the Manson murders is explained but not exploited, a spectre which hung over the place and sadly shifted its former open-window spirit. But rather than end on a tragic note, Harvey’s narrative extends the spirit into the new generation of unique canyon music-makers, such as Lili Haydn and Priscilla Ahn.

If you want an idea of what this canyon of dreams was like, why it was important, and why there was so much romance and inspiration all in this one place at this one time, this is the book for you. High kudos to Harvey Kubernik forever for getting it so right.

![]()

Mark “Pocket” Goldberg

Off the Alleyway

By Paul Zollo

Mark “Pocket” Goldberg * Off the Alleyway * Fantastic. This is very much the real deal. A brand-new blues classic is in our midst. A masterpiece gumbo of timeless gusto and groove – the fluid, living blues – a substantial injection of joyful roots music welcome now more than ever in these rootless times. It’s the new record by Mark “Pocket” Goldberg, long a beloved fixture on the L.A. music scene. Within the first measures of the opening song, “No Mercy for the Wicked Blues,” you know you’ve come to the right place. Here comes a great grinding groove, wailing harmonica, beautifully raw and metallic slide guitar, and Pocket walking through the blues on the big bass while singing with the ragged authority of a bluesman doing it for many more decades than he’s been alive. It’s like walking into one of those late-night jam sessions that the best cats play after their real gigs, just music for music’s sake, great musicians playing the greatest songs long after the waking world is asleep.

These songs resound like new classics already. The man has dug deeply into the traditions of the blues – the raw Chicago blues, the blues of Willie Dixon – with whom he performed (it’s true: when Willie, the father of blues bass needed someone to play while he sang, he called up Pocket). Like Willie, Pocket not only knows the heartbeat of the blues as emanating from a stand-up bass, he knows how to write a great song. He also reaches beyond the realm of that time and place, yet everything he touches is informed by the deep vibe of Chess Records and its ghosts. He knows great records are about precision, sure, but more about the groove, the performance, the soul and swing of musicians interacting. The level of musicianship on this is just astounding, centered around the deep pockets that Pocket defines with drummer-percussionist Debra Dobkin, Nick Kirgo’s delicious slide flourishes, solid rhythm and stinging electric guitar solos, glorious horn section dynamism and the harmonica and accordion vigor of David Fraser. Kirgo and Pocket produced this along with Dobkin, and Kirgo did the mix – and a great mix it is, as there’s a vast diversity of elements woven throughout this tapestry, and yet the soundscape is warm and clean.

Pocket’s level of songwriting excellence is as high as his musicianship, and with a wide range. If Stephen Stills and John Fogerty wrote a song together, it might sound something like “Lost Another One Blues,”built on a vigorously solid groove between Pocket and James Gadsen on drums, and with the best swampy horn chart I’ve heard in ages, arranged by trumpeter Darrell Leonard and performed with his Texicali Horns. The legendary Barry Goldberg reminds us how great Wurlitzers can sound when someone great plays them – his rhythm part on this one sparkles and then leads into a great and spirited solo, that then segues another great Kirgo guitar solo, as bright and bluesy as Clapton at his best. “Whistlin’ Away” is a lovely ballad, like when Tom Waits stops to sing something slow and pretty. Written with David Morgan, it’s a sweet and gentle detour, but not a lightweight one. Willie Nelson could sing this; could be a country classic. “Bumps In The Road,” with its jaunty beat, brings to mind Willie Dixon’s reminder that the blues aren’t always down and out, and often sing of survival and triumph. It’s a message woven throughout all this music, and is the essence of this song: it’s not what happens that matters, it’s how you take it. “Down Home Woman” is pure blues fervor while “This Train” is haunting Americana, timeless in its slow shuffle, a train song you could hear hobos singing in the whiskey moonlight. “Best Be On My Way” sounds like something cooked up in the basement by The Band with Levon Helm digging into the vocals and drums. And it all concludes with the bouncy “Bounce,” which is just drums & voice, fusing a kind of African drum & percussion track with Chicago gospel vocals (arranged by Terry Evans) and a great Pocket vocal in the center. This is a man who knows his own mind and his own music, knows how to kiss a groove into perfection, and knows how to write songs with a graceful simplicity. And simplicity, as all musicians know, is a complicated business.

If you’re tired of bloodless and relentlessly robotic music, and who isn’t, take this album as have I as a perfect antidote to all that ails us. In times like these, when people are more fragmented and crazy than ever, flooded by the overload of information and junk-mail, authentic music – music by humans for humans – is needed more than ever. This is real music for our increasingly unreal lives, and it couldn’t come at a better time.

![]()

Dan Hicks & The Hot Licks

Crazy for Christmas

By Patricia I. Escárcega

Dan Hicks and the Hot Licks * Crazy for Christmas * The nights are getting long and cold, and the scent of snow is in the air, meaning only one thing: it’s Christmas album season again. Every year, a fresh tide of new Christmas albums wash up on store racks, a buffet of all-you-can-eat seasonal music ranging from traditional Celtic solstice celebrations to contemplative Gospel classics to slick new pop renditions of favorite old carols.

The ever-growing heap of Christmas records begs the question: why bother? We have enough classic Christmas recordings to play from here to eternity. And let’s face it, the Christmas album genre has earned a low reputation as the province of schmaltzy novelty records and overproduced, derivative Yuletime musical train wrecks. So it’s no wonder some of us approach Christmas albums with great skepticism and trepidation—or avoid them altogether. Come December, you can’t swing a candy cane without being assaulted by another sticky Santa Claus ditty. So, why bother with another Christmas record?

Let us thank Dan Hicks and the Hot Licks for bothering. Anyone remotely familiar with Dan Hicks’ brand of rhythm-happy Western swing and country jazz would tell you that if anyone can make Christmas music listenable again, Dan (and his merry band of Hot Licks) is the man. And they would be right.

Crazy for Christmas is loaded with enough down-home, toe-tapping charm to remind you—in case you had forgotten—Christmastime can be fun. From the upbeat, geared-up opener “Christmas Mornin’” to the sweet jazz romance of closing track “Under the Mistletoe,” Dan Hicks and The Hot Licks offer up the perfect soundtrack to replace that insipid smooth jazz playing at the office Christmas party. “Carol of the Bells” and “Run Run Rudolph” get the Hot Licks treatment here, the standards coming to life again with a dose of Hick’s swagger, a handful of jazz chords, and the Hot Licks’ impeccable rhythm section.

Are there any budding new Christmas classics here? I nominate “I’ve Got Christmas By the Tail,” a laidback antidote to the frantic rush of un-merry stress that takes over people’s lives come December. “Ain’t no Christmas gonna get me down , I’m not doin’ no runnin’ round,” Dan sings. “I show Christmas who’s boss / And if Christmas don’t like it, it’s Christmas’ fault.”

That’s the kind of Christmas spirit we could all use.

![]()

Copal

Into the Shadow Garden

By MATTHEW CAMPBELL

Copal * Into the Shadow Garden * New York City outfit Copal release their debut album, Into the Shadow Garden this month. A beguiling and somewhat mysterious effort, this record lives up to some of the hype, indeed mixing old-world Eastern European, Middle Eastern and Nordic influences with more modern instrumental elements.

The record opens with a faded-in drone, instantly creating an atmosphere of mild tension that remains throughout most of the album. The first rhythmic element to appear is a pulsing yet reserved bass line courtesy of bassist/keyboardist Chris Brown, followed by drummer Karl Grohmann’s laid back groove. The rhythm section on this record remains solid and focused throughout, yet plays just enough behind the beat to give the impression that the listener is somehow gliding along upon a mystic, old world dreamscape. Flourishes from leader and composer Hannah Thiem’s violin first appear at this point, as do the primary harmonic accompaniment, the cello. It is the melodic interaction of Thiem’s violin and the cello of Isabel Castellvi and Robin Ryczek that stands out most on this record – the cellos often lay down a drone that provides an anchor for Thiem’s modal improvisation, while at other times they harmonize, with a tendency towards 4ths and 5ths in their harmony – this element in particular evokes a distinct ‘East meets West’ feel. In between all these elements, bassist, keyboardist and sound designer Chris Brown provides the finishing touches, filling out the sound with Fender Rhodes, sound design and synth pads.

All of these elements are put together with aplomb, taste and professionalism. This is undoubtedly a record that delivers in terms of its slick sound, crisp, world class playing and competent improvisation. It is quite evocative in the sense that the harmonic structures being used are instantly recognizable by even the least educated of listeners as ‘ethnic’ in its sound. It is here that I find fault with the record, however.

I found upon listening the first time, it was too easy to dismiss the record as same-ish, ethno-classical wandering over professional session playing. I found it much easier to picture a New York session drummer playing with headphones in a high class studio than to picture deep forests and mythical streams. It was only after a second and third listen that some of the melody lines, harmonic intricacies and rhythmic subtleties had embedded themselves in my mind enough to start to ignore those initial impressions. Indeed, Thiem’s melodic and harmonic tendencies show a very talented, highly musically educated mind at work, but I would have preferred to hear a little more ‘grit’ in the work, a little more street-wise direct emotional expression, instead of the somewhat alienating crispness of a too-perfectly played and produced record.

Many people may find it hard to look past this album’s very slick exterior into the heart of the compositions – Into the Shadow Garden seems somewhat guarded, reserved, even unable to express itself to the fullest extent. However, an educated and patient listener, who is willing to put a little work into this record will enjoy it immensely. It is not only professional and slick, it is also evocative and genuine – all in all a very worthy debut album indeed.

The Brothers Landau

Parallax

The Brothers Landau * Parallax* IN A WORLD of ceaseless audio overkill, when so much of music seems bloodlessly artificial and relentlessly robotic, hearing this new record by The Brothers Landau is a revelation and a joy. Here comes something authentic, something delightfully organic. Viscerally lyrical songs sung and performed by two brothers in perfect musical synch, this is a warmly dimensional collection of discovery.

The heart of their music is acoustic: two human voices, a cello and an acoustic guitar. And really good songs. They do it all together, the brothers, the playing, the singing, and the album doesn’t even designate who does what, including writing the songs. But that seems to be the point, that it doesn’t matter – this is a package, and a God-given one. Like other famous musical sibling groups, such as The Everlys, McGarrigles and Roches – there’s a wonderful intimacy achieved when these voices blend, a soulful closeness that adds a graceful gravity to the sound. The greatness of some of the most famous vocal combinations – such as Simon & Garfunkel and Lennon & McCartney – was achieved because the singers grew up together almost like brothers, and had been matching their voices together since they were kids. The Landaus do it naturally and knowingly, and the effect is that of two souls merged, which empowers the spirit of each song.

That telepathic effect is also present in their playing, and in the inventively organic ways they combine cello and guitar. On the lovely “Penny Parade” when the cello segues instantly from a chordal support part to an achingly melodic solo, and then rests as the guitar takes over, you hear it. It’s an intimate and empathetic interchange, the sound of two musicians who have played together their whole lives. Their musical foundation is sparsely simple, two instruments and two voices, yet in these limits they’ve discovered limitless possibilities. There’s a lot of inherent resonance to the combination of acoustic guitar and cello, as both are instruments with vast tonal and emotional range, and the brothers take full advantage of the potential of combining their two instruments in every way imaginable. Never, though, does it seem contrived or created merely for effect; the shifts in attack and support are fluidly organic, and always in service of the song. A keenly orchestral dynamic flows organically through the entire album, as successive counterpoints of bass, rhythm, chords and melody intertwine.

Self-produced, it’s a collection of often complex songs – shifting grooves, tapestry guitar and cello parts abound – so they wisely didn’t overwhelm in the production what is already a heady brew. There are other instrumental colors besides the cello and guitar, such as piano, cymbal crashes and accordion – but all are acquiescent within the guitar-cello matrix.

And they don’t shy away from letting the cello be a cello – and calling on the ghosts of Stravinsky and Zappa in wonderfully dissonant parts, as in “Watch What You Say.” An acoustic Yes-like suite which veers into unexpected dissonance, this is progressive folk, but better than that sounds. Essential and alive, this revels in the full-bodied tone of the cello with passages of unbridled fury and hushed melodicism. This is cello created not by an arranger at a piano, but by a cellist, and one who is happy to veer from the usual conventions. It might dissuade some listeners who don’t want to venture too far from familiar turf, but for those who delight in music of discovery, this will be a enjoyable journey.

“The Price” is maybe my favorite track on the record, a confident and beautifully winding dirge-like melody lovingly accented by sparse percussion and touches of piano, accordion, and cymbal. It’s a song about how much can be achieved when we let go of that which reins us in. It’s about music, it’s about life, it’s about love. The progression from verse to chorus is seamless, and the lyrics flow with a conversational flair, lovingly underscored by the high harmony.

“What Does It Take” has a dash of Todd Rundgren-like tunefulness that matches ideally the longing of the lyric. “Start Dancing” starts with on a complex but appealing descending guitar riff around which the entire track is built, and a solid groove is built with only shaker and the interplay of rhythmic cello and guitar. “All We Know” is an alluring rhythm tune, somewhat reminiscent of Dave Matthews’ chordal and melodic playfulness, simple and complex at the same time, culminating in a wonderfully inventive counterpoint of vocals.

It all ends with the instrumental “Good Things,” a happy place to end this journey, as the cello sings a timelessly charming tune against an upbeat Brazilian-inflected guitar rhythm and changes. It’s a promise of more good things like this to come, and with as much taste, grace and panache as the Landaus exhibit on this outing, it’s bound to be good. Let’s hope the Landaus are one brother team that stick it out, and continue to explore their twin journey of harmony. – PZ

Raspin Stuwart

We Do What We Do

Raspin Stuwart * We Do What We Do * The cliché is that you have to be a kid to make a dent these days in the music industry. Raspin Stuwart is the exception to that rule. At 53, after 28 years of running a publishing empire that produced two of Los Angeles’ most beloved monthlies, Boulevard and Gorgeous, he’s retired to finally focus on his true love: music. And he’s making some serious waves. Not only is he selling out shows around Los Angeles, he’s also been picked up by Starbucks to be a featured artist.

A tremendously soulful singer and songwriter who has been described in recent reviews as a “force of nature” who is “in the business of showstopping,” he’s also a humble and warmly humorous man who is presently bringing his music to the attention of the public in a variety of ways. As a magazine publisher, he was known to make connections within diverse pockets of the L.A. population, so that the appeal of his magazines crossed over a multitude of cultures and attitudes.

Now he’s bringing that same savvy to the problem of how a musician gets his music heard in the chaotic context of modern times. It all starts with the tried and true: live performance, connecting directly with people and giving them a needed respite from the everyday cavalcade of electronic entertainment.

“It’s all about the people,” he said, “about building your fan-base. It’s about connecting. The thing people talk about most is a feeling of love, of compassion and forgiveness.” His recent sold-out live shows in Los Angeles have reflected this conviction, garnering critical raves for both his performance and his songwriting, rare in this city of jaded critics, and generating an ever-expanding audience for this singular artist.

Raspin has one solo album in release, the critically acclaimed We Do What We Do. If you are the kind of listener who prefers albums that don’t stray too far from a single style and tone, you won’t like this one. But if you long for those days when albums could possess a veritable rainbow of musical styles, embracing folk, jazz, blues, gospel, rock and soul all at once, then you’ll love this, his debut .

Raspin is a powerfully passionate singer who has mastered many vocal styles, from the soulful Louie Armstrong/Tom Waits gruffness of the opening track “Rumblin’ and Tumblin,'” through the resonant and clear folk tones of “The Bitter End.” He’s a strong melodist whose songs, whether upbeat or ballads, always possess an appealing tunefulness, especially in this rhythm predominant age. “Somewhere In Time,” for example, is an absolutely gorgeous melody, as is the haunting “Hold On.”

His songwriting is richly multicolored, carrying the listener through a kaleidoscopic listening experience, but it’s unified by passionate vocals throughout (both by him and others) and by the consistently high level of the musicianship.

The album was produced by Raspin with singer-songwriter producer Jeff Gold (who also mixed the recording). Faced with such a wide range of stylistic approaches, they did an impressive job of rising to the challenge of framing each song, while still creating an organically unified album. Part of this problem was solved by bringing in stellar musicians and singers, whose fine playing and singing enriches and connects each track. Timothy Emmons provides wonderful great acoustic bass playing throughout, regardless of style, and also fine cello work on several tracks. The harmony singing throughout is absolutely tremendous, thanks to the presence of many gifted vocalists, including the fabulous Tata Vega, whose voice brings genuine soul to any track it touches.

Raspin is an evocative writer, and his songs often have a real sense of time and place, which he and Gold exemplified in their production approaches. “Busy Sidewalks” for example, is an L.A. street song dressed in the music of the streets; not gangsta rap, fortunately, but authentically conveyed, richly textured street corer doo-wop. “Hold On” is an achingly beautiful ballad that reflects on the importance of preserving love, and is framed elegantly with acoustic bass and cello, acoustic piano and oboe. “We Do What We Do” starts off with a slow, loping country-rock feel, as if we have just walked into a sixties rock opera with a smoking old-fashioned B-3 organ playing at its center.

“Smoke the Hookah,” which also conjures up certain spirits of the sixties, is a song well-known to those who have caught Raspin’s shows over the years, and this version stays true to its surreptitious but celebratory Turkish feel, especially the ancient, ghostlike harmonies that sound as if they emerged from 18th-century Marrakesh. “Midtown” has a brisk urban feel that matches its “On Broadway” like urban imagery and inspirational tone, and “The Bitter End,” which closes the album, is spiritual amalgam of folk and soul, enriched by powerful soulful background vocals.

This is an eclectic album, but it’s a healthy eclecticism, bringing to mind great albums of the past that propelled listeners on substantive musical journeys. If your aim is to stay in one musical place at a time, this probably won’t work for you. But if you are up for adventure, get aboard; this kind of journey is good for the soul.

Recently, Raspin has succeeded in capturing the attention of Starbucks, who have evidently recognized that his style of soulfully seasoned folk is ideal for their stores. Several of his songs are now in constant rotation, along with that of other musical luminaries, on their daily broadcasts, which are heard in more than 16,000 Starbucks around the world. Not a bad way to get your music to the public. When he does something, he does it big.

Raspin’s the rare modern man, one who diverged from his dream to build an empire – miraculously producing two healthy magazines in one of the most perilous periods ever for print journalism – only to return to that dream after nearly three decades with a genuinely infectious spirit that is drawing people of all ages to his music. He’s a guy with a golden touch, and that he’s applying that magic to music at this time is lucky for us all. –P.Z. www.raspin.com

Bob Malone

Ain’t What You Know

Bob Malone * Ain’t What You Know * Delta Moon records * A new peak in what’s been a rather mountainous career, Malone’s latest shows off everything that makes him great and more. Produced by guitarist-extraordinaire Bob Demarco, and anchored by an amazing rhythm section comprised of the combustible combination of Lee Sklar on bass and Mike Baird on drums, Malone’s musical load seems lightened, freeing him up to bring some of his most dazzling playing yet to a record. Combining the heat of his live performances with tracks of deep rhythm and soul, this record covers a lot of musical ground, from the folk-rock exultation of The Band’s “Cripple Creek” through the tenderness of “Butterfly” and the darkly cynical “No One Can Hurt You.” The opening track “Why Not Me,” co-written with Demarco, is an audio feast, peppered by Malone’s great horn arrangement and Demarco’s gumbo of guitar colors. Incandescent passages like the seamless procession of a Demarco guitar solo into a Marty Rifkin pedal-steel flourish into a Malone piano outing on the title song make this the kind of record you can listen to over and over, the way records used to be. Great songs, amazing production and playing, it doesn’t get much better than this. — P.Z.

Rickie Lee Jones

Balm of Gilead

Rickie Lee Jones * Balm of Gilead * Fantasy * Perhaps the most remarkable thing about Rickie Lee Jones’ records is the range of emotion expressed, from deep sorrow to pure joy, and this new record has both. There’s “Bonfires,” a poignant and very loving heartbreak song in which the singer burns everything she has, yet reminds the subject that he “is the sweetest boy I know,” which makes the truth of her pain so much more palpable. To the other extreme is the “Wild Girl,” which starts as a song of memory of one’s own wildness, and then morphs into a song of celebration, both for her daughter’s 21st birthday, and for her own parental triumph, all tempered by a simple but haunting melody. Her duet with Ben Harper on “Old Enough” is about real joy, the kind that comes from knowing all we’ve lived through to get to this place. And there’s much more. This is one not to be missed, kissed with the promise that meaningful songs still matter. –Paul Zollo

Paula McMath

Trust The Sky

By PAUL ZOLLO

She writes the kind of songs people say nobody writes anymore. The kind of songs written by the greatest of the great singer-songwriters – songs with uniquely poetic lyrics wed to gorgeous melodies, songs in which both the words and the music are equally inventive and inspired. In great songs, it’s not the words or the music that matter most, but the way in which they connect. In her songs the melodies and lyrics glide together with the immaculate dynamism of figure skaters. The haunting “Trust The Sky,” for example, is a song of quiet zen acceptance, of learning to trust the universe. Its tune is ripe with unexpectedly delightful melodic passages, such as the bluesy turn on the title phrase at the end of each chorus. It’s surprising and beautiful, as is this entire album. Add to that a bridge of aching yearning that resolves into a sparsely tender acoustic guitar solo, surrounded in loving instrumental touches, combined with a lyric of gentle confidence, and you have something timeless and great.

The production throughout – as steered by Paula with the multi-instrumental Ian Hattwick (who also co-wrote several of these songs and contributes lovely musical touches to each track) – is wisely subtle, always understating the arrangements to enhance rather than overwhelm these powerful songs. These songs are not only inspired, they’re crafty – designed by a savvy songwriter to last, so that they won’t fall apart on the street like a cheap radio. But they are singularly uncontrived, which is the hardest challenge for all songwriters, met and surpassed by Paula, to write something which is fresh and unheard, yet alive with a timeless inevitability. Her songs sound great on first listening, and only grow richer in time.

“Without Ever Saying A Word” is a breathtaking ballad that is brilliant in its simplicity. Kind of the lyrical flipside to George Harrison’s “Something,” it’s built on a clever conceit but easily transcends cleverness to pinpoint an intangible, always a hard hurdle to clear in the realm of romantic songs, and with a gorgeous tune. “So Long” is a great upbeat declaration, and on it she bears the kind of edgy but passionate feminine presence of a Liz Phair or Patti Smith. Sparked by an unrestrained electric guitar solo by Hattwick, it shows the range she possesses, from tender ballads to rockers. The poignant “3 Flights of Stairs” displays the kind of lyrical spell she can cast, as she projects images of fragile vulnerability, connecting this stairway to a person’s crooked spine so that we not only recognize her subject, we internalize it.

That this is her debut album is hard to believe, because it resounds like the work of a mature, experienced singer- songwriter, someone who’s been doing this for decades. But like Laura Nyro, Carole King and others who wrote inimitable masterpieces from the very start, Paula is a prodigiously gifted singer- songwriter who has taken her inherent abilities and soared with them. With clear and confident vocals and a natural gift for harmony singing (she beautifully overdubs harmonies with her own voice with the warm assurance of Joni Mitchell or Dan Fogelberg), she has everything it takes and more to be a lasting presence in our musical landscape. In a world where there seems to be too much of everything except time to take it all in, this is a collection of songs that demands attention, and given it, it’s time well-spent. This is a record that makes no promises it doesn’t keep, but culminates in the promise of more to come. Paula McMath is very much the real deal, an artist plugged directly into the electric current of creativity. This is not to be missed.

Carrie Wade

The Old Ways

By PAUL ZOLLO

Carrie Wade is a seriously great songwriter. There’s a whole lot of people writing songs these days, and it’s always evident which ones have the gift, the spark, and which don’t. Carrie Wade has that spark. And that natural talent combined with years of musical and life experience has resulted in a songwriter who embraces the full gamut of life in her work, and always gracefully and uncontrived. This is genuine. In songs like her title tune “The Old Ways” and “In A World That Goes Wrong,” she fuses a prodigious gift for tunefulness with poetic lyrics of unforeseen candor. She’s a gifted melodist, and her archly angular yet irrepressible tunes bring to mind Neil Young and early Joni Mitchell, as in the title song, simultaneously sophisticated and simple, and exceedingly inviting. Her lyrics strike that crucial balance between the colloquial and the poetic, and her soulful vocals are reminiscent both of the aching purity of Emmylou Harris and the wounded bravado of Chrissie Hynde. She’s a savvy artist in a multitude of ways, not the least of which is her choice of co-producers, New Zealand’s Peter Kearns and America’s own Marty Rifkin (legendary for his pedal steel playing with Springsteen and others). Both are hands-on multi-instrumentalists who draw from their own seemingly limitless instrumental palettes, but always in service of the songs; the production throughout is gently inventive and dimensionally evocative, surrounding yet never overwhelming these heart songs with a happy and rhythmic luster. Carrie’s message throughout is a positive one, that although our lives are often painful, such sorrow and struggle can deepen the artistic well and strengthen the soul. “In A World That Goes Wrong,” which is beautifully colored by Rifkin’s haunting pedal-steel passages and Kevan’s Torfeh’s mournful cello, we get a declaration of triumph, of transcending everything modern times presents to derail an artist. That sense of triumph shines throughout The Old Ways, and it’s a welcome sound in these trying times. Keeping hope alive is perhaps the greatest challenge we daily face in these chaotic days, and music like this goes a long way in helping us all remain hopeful.

Cargo Cult

Lonely House (Covers)

By PAUL ZOLLO

Had Coltrane never recorded “My Favorite Things,” it’s quite possible that his genius might have gone unheard by millions of his fans who were attracted by the famous melody. One hopes this new album by the remarkable trio Cargo Cult (Tomas Ulrich on cello with Rolf Sturm on guitar & banjo and Michael Bisio on bass) has the same effect, luring listeners in with famous melodies so that they then become exposed to the expansive improvisational genius of these three amazing musicians.